Today I am feeling the pressure of cabbage. Really, cabbage. The opaque vegetable reminds me of a fat baby-faced candle you keep peeling back, only to find it has no wick, just a ruffly heart that, at the last, clings to a core of root flesh and holds nothing but air.

It is not particularly in the nature of cabbage to pressure people who have too much to do and too much on their minds. Cabbages are rather humble things, yielding to knives for the sake of coleslaw and to peasant hands for a laying open to receive stuffings of onions, rice and ground beef.

The other day I met a man who knows about stuffed cabbage. He and his wife like to eat it. They also like to eat pierogies. I ate both as a child, because these foods were part of my stepfather’s Eastern European heritage. I still like the pierogies and have recently taken to buying them, but I never learned to like the glumpkis, which is what my stepfather called the stuffed cabbage, or maybe just what my mother called them because that’s what she thought he had told her.

I don’t know what the man I met called them. The word he used also began with a “g,” but it was different. I admit I was lost in my own memories and so didn’t pay close enough attention to the sound, or ask for the spelling. I was busy recalling how I had been forced to eat them, and now I’m remembering just part of why I resisted.

After all, we also dubbed these rolled packages pigs-in-a-blanket. There is no pork in the cabbage (at least there wasn’t in ours). It’s just the way the stuffed rolls look when you lay them side by side in a long glass dish: little pigs in blankets that, once baked, turn to wilted translucence, absorbing the red sauce on their backs, to finally reveal a pulse of gelatinous rice and fat innards. In contrast, I always preferred pierogies— dough half moons fried in butter, their coverings browned to a crisp, their hearts of potato and cheese kept secret, until I chose to reveal them with the pointed application of knife and fork.

Like I said before, it is not particularly in the nature of cabbage to pressure people. But I’m feeling the push, because I have a theory about something I call writing-in-place, and I want to show that is not just an idle idea but a real technique that actually works. Enter the cabbage.

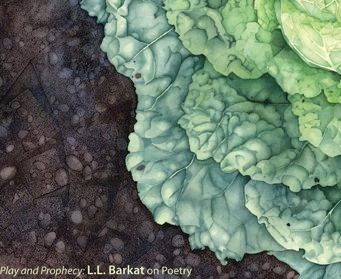

At my bedside is the new print issue of Englewood Review of Books. The winning painting for their food-art contest is on the cover. It is a beautiful, artful rendering of… cabbage. The artist took a top-down view, which shows how cabbage is a fist that keeps losing its sense of holding on, as the outer leaves gradually yield to gravity and lay themselves down to sun and dew and a painter’s keen eye. In this way, a painter can capture not just the ruffles and the layers and the variance in tone, but also the very veins that thread through leaves and somehow seem to be part of the opening process.

As fate would have it, I am on the cover with the cabbage. In delicate sea-green print, I am noted to be the subject of an interview on play and prophecy in poetry. There are a few other names on the cover too, but mine is closest to the cabbage.

I remember the day I first saw the cover. “I’m on the cover with cabbage,” I observed in a Facebook status update. It amused me to say this, but now I know it has become a somewhat more serious issue. For the reality of the placement has invited me to prove my writing-in-place theory, on a day when I am overwhelmed and cannot think of a single thing to write about. Me, beside the cabbage, is a challenge to tell the world that the writer is never at a loss— nor the dancer, the painter, the musician, nor maybe even the scientist or the mathematician.

Because, somehow, rooted in place, even in place with a lowly cabbage, we have everything we need to get to the heart of things, to open the hand of time— to reveal our past and maybe to shape our unsure future.