“If you didn’t take the picture, you weren’t there,” Garry Winogrand once said—although perhaps he didn’t intend for his words to be quite so prescriptive. Since 1990, the number of photos taken per year has increased by about 600 percent—in part because of the technological advances of the camera (the disposable camera in the late 1980s, the digital camera in the mid-1990s, and the camera phone in the early 2000s) and in part because we’ve adopted Winogrand’s sentiment as our gospel.

On the average day, over 55 million photos are posted on Instagram and 350 million are posted on Facebook. There are subcategories of “selfies”—the bathroom selfie, the post-workout selfie, and the funeral selfie—and a widespread compulsion to photograph what one is eating. We take a lot of pictures—obsessed with remembering, anxious to be seen, the curators of the galleries of our own lives. If we don’t photograph the meal, will it taste as good? If we don’t Instagram the sunset, did we actually experience it? If we don’t take the picture, are we there?

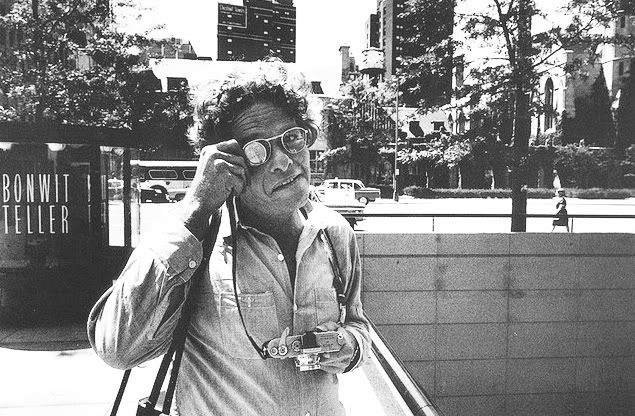

Winogrand lived by his words, shooting 26,000 rolls of film over the course of his life (2500 of which were left undeveloped when he died). This summer, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has been hosting a retrospective of Winogrand’s work, curated by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the National Gallery of Art. The exhibit is divided into three parts, “Down from the Bronx,” photographs Winogrand took of New York between 1950 and 1971; “A Student of America,” photographs he took across America as part of a Guggenheim fellowship; and “Boom and Bust,” photographs he took of Texas and Los Angeles from 1971 until his death from gall bladder cancer in 1984. The exhibit features just over 175 images, 50 of them posthumously printed and never before seen. It is now entering its final week at the Met, and if you can make it there before it closes (September 21), it is well worth your time.

Born in the Bronx, Winogrand started off as a magazine freelancer (for Sports Illustrated, Collier’s, Red Book, and occasionally Life), but quickly found the kind of work magazines wanted limiting. (Magazines wanted the shot of the touchdown; Winogrand wanted to shoot the tired football player hunched over on the bench in the rain.) So, he turned to the streets—and became one of the most prolific photographers of the 20th century.

He rarely left his house without his camera, and his son remembers consciously walking behind him instead of in front of him whenever they went out, so as to not disrupt any potential shot. He was constantly clicking. “I photograph,” Winogrand said, “to see what the world looks like in photographs.” His work is decidedly modern: he entered the art scene in post-World War II America when what constituted art was being redefined and reimagined—Warhol’s pop art, Pollock’s abstract expressionism, and the rise of the New York School of photography (Saul Leiter, Diane Arbus, and Robert Frank, among others)—and his work was twice showcased at the Museum of Modern Art during his lifetime.

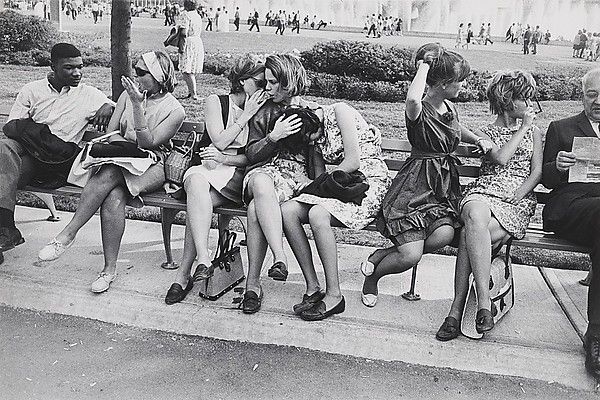

Winogrand photographed life as it happened, as it is—with no agenda to frame things in a certain way or to get a particular message across. Writes Holland Cotter in the New York Times review of the retrospective: “Photographs don’t change anything, [Winogrand] said, and shouldn’t try. They’re not about morality. They’re about recording what’s going by.” The effects of this posture toward art left me thinking several times during the exhibit, “Hey, I could’ve taken that.” (A snapshot of a sign at the Central Park Zoo comes to mind.) At times, Winogrand’s photography feels haphazard, like he was just flinging his camera around, snapping without looking.

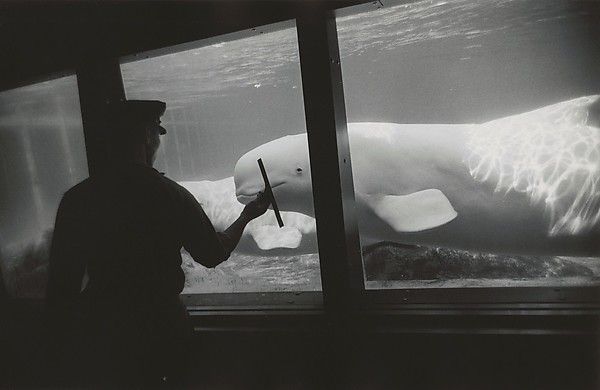

But others of his photos are beautiful and gripping. He loved photographing women, and several of the featured works show a vibrancy to womanhood that’s captivating—a socialite smiling and dancing at Harlem’s El Morocco, a woman tossing her head back in laughter as she eats an ice cream cone. A shot of a toddler standing in his Albuquerque driveway is strangely enthralling; a photo of a biracial couple at the Central Park Zoo makes one wonder if he was providing some sort of commentary on race in America or merely capturing a moment (His thoughts on what photography should be suggests the latter). My favorite photo in the exhibition is of a hand feeding an elephant’s trunk.

I went to the Winogrand exhibit twice this summer and lingered in it for quite some time both visits. I’ve been trying to pinpoint why exactly I enjoyed it so much, particularly because other friends found it underwhelming. I think it captured my attention because it offers a glimpse into a past America—the hope and prosperity of the post-World War II years and the restlessness and riots of the 1960s and 1970s—an America I’ve read about, an America I’ve watched Mad Men episodes about, but an America I’ve rarely seen presented so candidly.

Winogrand photographed this American life—or that American life, rather—well-dressed businessmen and women walking down the street, swimmers at Coney Island, John F. Kennedy at the Democratic National Convention, a bespectacled man at a Nixon rally, a stark naked man running through Central Park on Easter Sunday, travelers waiting at the airport, Vietnam protestors, fairgoers at the Texas State Fair, a young Drew Barrymore at the Academy Awards.

“You could say that I am a student of photography,” he once said, “and I am; but really I’m a student of America.”

That is what I find compelling about his work—his desire to capture a society, a country, and a people. And that is what I think so many of us are missing as we eagerly snap away on our iPhones. Instead of using photography as a means of seeing others and the world, we use it simply as a means for being seen, a digital keeping up with the Joneses.

“I feel like the world is a place I bought a ticket to,” Winogrand once said—and that’s the spirit. The next time I pull my phone out of my bag to capture a moment, I’ll pause and ask myself if it’s an exercise in narcissism or an exercise in wonder.

Objects from the exhibition can be seen here.