“I want to drill!”

“C’mon, baby, no dry holes!”

“Oh, you hit another well. Now you’re making 13 million a month. Shocking.”

“The only way you get so much money is because you play off of my exploratory wells!”

“Crap, the EPA fined me again. I’m already $1 million in debt.”

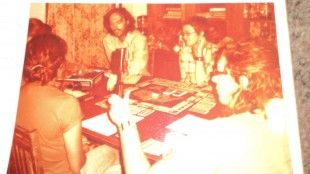

This was the conversation of a seminarian, a musician and a journalist, all in their twenties, sitting around a table. In the middle sat a square board with a picture of the United States of America, not divided into states, but instead into prominent oil and gas reservoirs. None of them were for exploiting the land. None stood behind Sarah Palin and chanted “Drill, baby, drill!” Yet around this table, each one couldn’t think of anything besides buying up the most leases and maxing them out with wells. They were playing Wildcatter: The Authentic Oil & Gas Exploration Game, and the ethics of reality quickly fled in the pursuit of being the richest Wildcatter.

“The guy that drills the most has the most chances of coming up with the most.” – H.L. Hunt

That’s the quote you’ll see on the side panel of the board. On the front of the box, a blackened Spindletop silhouetted against a Texas sunset spews its glorious 75 thousand barrels of crude oil which it continued to flow out for some time – the gusher that started off the Texas oil boom in 1901.

Flip the box to the back. Underneath the description of the game, J. Paul Getty’s modern interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount serves to get players in the proper mindset – “The meek shall inherit the earth, but not the mineral rights.”

Oil is not for the meek, and wildcatting is not for the cowards, even if you’re only playing a board game. The object of the game, as written in the instruction manual, “is to become the RICHEST Wildcatter by leasing property and drilling oil and gas wells in the major producing areas of the United States.”

“I made the game to show people how difficult the oil and gas business really is,” Ken Kessler, creator of the game, says.

Kessler created the game in 1981, during a time when world demand for oil was shrinking (due in large part to conservation efforts) but the price was remaining stable due to OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) adjusting their output on the market. “If people knew how hard it was in the oil and gas company, they would be kissing the oil and gas companies feet instead of cursing their face,” Kessler insists.

The game isn’t easy. In some ways, the game is the more historically correct Monopoly – Standard Oil Company being one of the biggest corporations to be broken up by the Sherman Act in 1912. There are no motels or hotels, no boots or hats to hop around the board. There’s no buying property, either. Each player gets a Learjet and $6 million. You purchase leases. The only thing a player really owns is the well or the dry hole they drill, and drilling is no cheap endeavor. Unlike the security of purchasing a hotel in Monopoly, in Wildcatter, you pay to drill. Then, you roll the drilling die to determine if the well is a producer or a dry hole. If it’s a producer, you pay double to complete the well and then may begin earning from it.

The manual specifies questions each Wildcatter should ask before drilling: “1. Does he wish to gamble his money trying to drill a producing well or wells?”

“When the price of oil went up, the oil companies became a punching bag for everyone, especially in Washington,” Kessler explained. This view of Washington might explain Wildcatter’s other difference from Monopoly. Whereas Monopoly has jail, Wildcatter has Washington, complete with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). To get out of Washington, a Wildcatter forfeits three turns and pays attorney fees of $100,000.

Though created in 1981, when Dallas was adored by fans, the game wasn’t released until the end of 1985 and was well received. Kessler says that even Neiman Marcus had put on order in. However, the game maintained this popularity for only a few months. It was in the spring of 1986 that several OPEC countries were to increase their output and cause the 1986 Crude Oil Price Collapse. The price of crude oil per barrel dropped from $23.95 to $9.86. Public fascination with crude oil also began to decline, and now, almost 30 years later, Kessler has a storage shed filled with the board games.

“The game should be selling at least 100,000 a year,” he told me, undaunted by the ups and downs that the industry has seen since his invention of Wildcatter, and again, oil has gained interest. With the pairing of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing that took place in the end of the 90’s, the world of unconventional shale reservoirs (like the Marcellus and Bakken shale) has become profitable, and it is the Wildcatters, those smaller firms willing to take the risk, that have made the most advancements in the field.

However, Kessler’s game does not account for fraccing or for horizontal drilling. “You know, people have asked me if I’ve thought about updating the game, making a current version of the game. But I never do, and I never will. I tell them, was Monopoly ever changed? No. It’s a classic,” Kessler says, still confident in his game.

At the time of this article, there is only one known retailer of this game, The Permian Basin Petroleum Museum. However, the California Oil Museum showed interest in carrying the game. Whether an updated version of the game would boost sales or make the game more relevant, the authentic oil and gas exploration offers the American dream: to fly around America on a Learjet as the king of oil.