“Alas,” said the mouse, “the whole world is growing smaller every day. At the beginning it was so big that I was afraid, I kept running and running, and I was glad when I saw walls far away to the right and left, but these long walls have narrowed so quickly that I am in the last chamber already, and there in the corner stands the trap that I must run into.”

“You only need to change your direction,” said the cat, and ate it up.

–A Little Parable by Franz Kafka

The insights of Kafka’s parables sneak up from behind, whisper “Guess who?” and leave before revealing themselves. Fate provides the DNA for his myths—mad dreams we can’t explain, but resonate with, as Joyce Carol Oates said, “feelingly.” Kafka’s universe is not evil. Its better nature has dozed off, or is catching up on a bunch of paperwork. But these fatalistic feelings so personal to Kafka’s sense of his own life describe modern life well, too. If a cosmic history book exists, the 20th century was recorded in Kafka’s handwriting.

The U.S.A.—the odd place where people happily buy and choose away their freedom—exists inside Kafka’s myth. Fate is the fog that enshrouds it. Life is one big trap, a labyrinth we forgot we’ve built, the spell we forget we cast. Every choice is a guess, every moment a lottery. How do we spring the trap, kill the cat and tear down the walls that channel us to the last chamber?

It’s impossible to repeal a myth with rational arguments or statistics. Facts are fickle things, able to serve any story. Trying to defeat a myth with serious speeches and weighty sermons is like trying to arm-wrestle an elephant—it just doesn’t make sense. Our concepts won’t save us. Only myths can fight myths. We need a myth to go toe-to-toe with Kafka’s bind—one light on its feet, with a good left hook, a chiseled jaw line, etc.

The answer may lie in the trickster.In a foreign land under a starry, dark sky a god is born. He is surrounded by animals, loved by his mother, and wrapped in swaddling clothes. His father is king of the cosmos, and his name is Jesus Hermes. This Greek god’s birth narrative includes the stealing of Apollo’s cattle and inventing the lyre. Hermes enshrines himself as a part of Olympus through humorous lying. Hermes is a trickster, the incarnation of ambiguity and change.[1]

In Greek mythology Olympus represents order, the proper ways of the world. Hermes exists to unsettle and confuse those ways. He is but one member of the trickster pantheon, along with Anansi, the spinner of webs and catcher of flies, the Norse Loki, the South African Eshu, Indian Krishna, the Native American coyote and even Br’er Rabbit. Each is a shifty thief who lives at the threshold, lord of the in-between, god of the hinge. The world is filled with hungry powers—traps and cats—and the trickster survives by outwitting them. They are liars, they are thieves, the weavers of false charms that every culture needs for its survival.According to scholar Lewis Hyde,

[2]

Tricksters violate life in order to maintain it, redraw social boundaries by crossing them, slip our orderly traps through humor and creative intelligence. Tricksters are the chiropractors of the communal imagination, loosening joints stiff with cultural arthritis. They exist as mockers who attack all mockers, archetypes that assault other archetypes; their lies lead to fresh truths, their thefts actually gifts. Hyde, again:

[3]

Every community has its Cheshire cat and needs its trickster, a character whose jokes inspire laughter that leave us with ideological vertigo. Their humorous message tunnels underneath the illusion that we are free from illusion. Not all illusions are evil and insidious. Fantasies, myths and stories are all part of what keeps human life human. Communal illusions rarely collapse under direct assault, but they do fall to a comic Trojan horse filled with truth. The best tricksters find and pierce the joints in institutional armor, unveiling the law itself as unlawful, toppling mini-North Koreas of the mind. Through the trickster, comedy’s cup overflows—our laughter means something—delivers us by undoing us. The trickster is the myth that shepherds us to a better reality. By disrupting the old spells and myths, the trickster creates new meanings, new boundaries, new futures.

Many artists claim something akin to tricksterdom. It’s easy to mistake oneself for a cultural prophet when one is actually just a contrarian asshole. Simply because what we say is right doesn’t mean we speak truth, just as being a fool doesn’t make us a holy fool. Much of art’s countercultural posture merely creates a more spacious and gaudy cultural cage. Those who claim to think outside of the box often live inside a slightly bigger box. Their idea of escape is part of the prison itself.

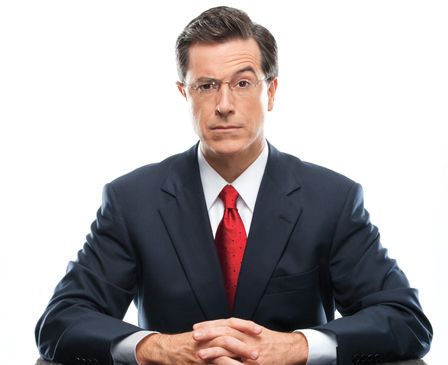

It might be helpful to point to someone who naturally appears as a trickster: Stephen Colbert. He resonates with parts of the mythology. He’s an equal opportunity mocker, politically androgynous, is probably the most feared interviewer in America and uses irony in service of political discourse. But his disruptions are domesticated. He is a fire contained, one that singes but never burns. Contra the trickster, Colbert’s irony never leaves the interplay of opposites. His irony only begets more irony. In a frank interview on Meet the Press in 2007 about the character “Stephen Colbert,” he says the following:

Tim Russert: But it is interesting in your program you’re not afraid to take on the press corps, the president, issues. I mean you do it in a humorous way…

Stephen Colbert: But there are no consequences.[4]

Tim Russert: But you’re still informing and educating and entertaining people.

It’s indicative that there has never been a real controversy or outrage over something Colbert has said, and ruffling Bill O’Reilly’s or President Bush’s feathers don’t count. In good Mary Poppins fashion Colbert has remarked: “Jokes makes things palatable….Comedy just helps an idea go down.”[5] But Colbert’s irony is all sugar and no medicine—I think it’s called a placebo. To play with a line from The Dark Knight, Colbert is the hero we want, not the hero we need. Have you heard that explosion of applause at the beginning of the show? Instead, the trickster lives by Christopher Hitchens’ maxim:

A rule of thumb with humor; if you worry that you might be going too far, you have already not gone far enough. If everybody laughs, you have failed.[6]

The trickster’s jokes—all the best jokes—remain about other people for around ten seconds. They wipe the smile off our faces with laughter. The trickster’s irony accomplishes something—it doesn’t co-exist with smug self-approval, but reveals that we don’t know what we thought we knew. The irony that acts as a restraining order on meaning, the “I-don’t-mean-what-I-say-irony” rhetorical device is an irony that isn’t really Irony, It never gives birth to more than words, never discovers the “acres of ignorance” within us.[7] Colbert’s irony is as predictable as a pop song and comfortably slips into bed with what we already knew all along: American politics and news can be absurd. The resultant knowing smiles and laughter frees [AJ1] you from having to do anything about what it mocks—making laughter itself problematic, unhumorous. In other words, Colbert is funny as hell, he’s truthy, the trickster myth courses in his veins—but he’s not a trickster.

If you are looking for a trickster, look to the margins. People tend to become tricksters when society gives them no other choice. Take, for example, Zora Neale Hurston. Her fiction, her autobiography (Dust Tracks on the Road) and her life move with a trickster’s agility—filled with witty lies that defrost the stiff hierarchies and boundaries of race, gender and class. Like one of her fictional characters, High John de Conquer, through her writing she “made a road where there was no road,” a road paved by laughter “that gushes up to retrieve sanity.”[8]

Cultures are healthier and more hospitable when they find themselves periodically disarmed of domesticated shalom. This is why Microsoft and Apple hire hackers to test their software—they reveal the glitches, the holes, the unknown. The trickster does something similar. In his hands, the truth becomes a lock-pick for stealing things that should be stolen. Every community needs a place for those who subvert that place. The trickster, with humor and irony, reveals the world as porous and comes as the ambassador of a better culture.

Every bit of seriousness, every household god and every sacred cow are ripe for mockery and theft by the trickster. Humor, funnily enough, is a seriously moral business. The road to truth is paved with balderdash. There is only one way to escape Kafka’s fatalistic parable, to undo the cruel joke we authored. We need a new joke—a joke so funny the cat can’t laugh.

[1] Anything good or interesting about the trickster in this segment comes from Lewis Hyde’s Trickster Makes this World.

[2] Lewis Hyde, Trickster Makes this World, 7.

[3] Lewis Hyde, Trickster Makes this World, 219.

[4] This point becomes even more pointed and problematic with one of John Stewart’s final statements at the Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear. He said: “If you want to know why I’m here and what I want from you, I can only assure you this: you have already given it to me. Your presence was what I wanted.” He and Colbert want viewers, nothing more.

[5] Stephen Colbert, on “Meet the Press,” October 14 2012.

[6] Christopher Hitchens, Letters to a Young Contrarian, 122.

[7] Guy Davenport, “The Scholar as Critic,” 95.

[8] Alice Walker, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston.”