Few things get Quincy Jones riled up like death.

First, it was Michael Jackson’s. Then, it was Vibe‘s.

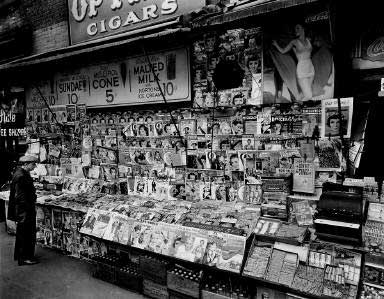

The monthly magazine covering black pop culture was shuttered suddenly last month 16 years after Jones co-founded it. The private equity firm that owned it failed to find a buyer. That was the only way to keep it solvent. The next day, after the news emerged, Jones vowed to revive it: “They just messed my magazine all up,” he told the Associated Press. “I’m’a take it online because print … is over.”

Perhaps he’s right. Maybe print is dead. Certainly, Vibe has company. It’s the latest music magazine to come to an end this decade: Blender, formerly owned by Dennis Publishing, which launched the lad mag craze of the 1990s, died last year. So did Harp, No Depression, and Resonance. Other glossies on life support include Rolling Stone (ad sales are down 21 percent), Spin (26 percent), and Sound & Vision (33 percent). Even Maxim, the Ur-lad mag of them all, is struggling. Ad sales there are down by nearly 35 percent (FHM and Stuff have already gone to Jesus).

Then there’s JazzTimes, the underdog under the radar. It folded in June, suddenly, and unlike Vibe, it did so without grabbing headlines. It never had a Quincy Jones backing it up. It never had Michael Jackson on its cover. But it, too, was looking for a buyer before it stopped printing, furloughed its staff, and sent its freelancers IOU’s.

Giving credence to Jones’s statement about print’s demise is the medium through which news of the magazine’s collapse emerged. It came from Jazz Beyond Jazz, a blog by Howard Mandel, the venerable jazz journalist. He confirmed a rumor and later noted that JazzTimes had joined Canada’s Coda (which ceased printing after 50 years), Mississippi Rag (35 years), and Britain’s Jazz Journal (30) in giving up the music-mag ghost. JazzTimes‘s official press release vowed a return after a sale was brokered. Mandel wasn’t holding his breath: “Resurrection is unlikely,” he wrote.

The problems facing newspapers right now have convinced some, like Jones, to think print is over. But what newspapers are facing seems categorically different from the current plight of music magazines. Significantly, newspapers haven’t had to deal with piracy, which over the past decade has reconfigured the entire recording industry and by extension reconfigured the landscape that music magazines cover. For newspapers, news is news, whether in print or online. Distribution is the problem, not the nature of journalism. For music magazines, the problem is existential. What is the purpose of a music magazine in light of the dramatic shifts of the past decade?

In 2000, CD sales, having survived Napster 1.0, continued their decline, but slowly. By the middle of the decade, they were in free fall. Just two years ago, estimates ranged from 1 to 2 billion illicit downloads a year. That figure is surely low now. The marketplace value of music has cratered. It’s expected to be free. Few really expect paid downloads to match, much less surpass, former profits. Most industry insiders, including musicians themselves, consider CDs to be a marketing device for live concerts. To have a hit record, furthermore, is almost meaningless when that means selling a few hundred thousand copies. Meanwhile, those able to top the charts are fewer and fewer in number. When people say Michael Jackson’s death signaled an end to an era, they in part mean there won’t be superstars like him ever again.

If there are fewer “hits,” and if there fewer people able to achieve “hit” status, that means there is less mass appeal and therefore less for a music magazine to cover. And if you are niched already, like Vibe (R&B and hip-hop) and Blender (top 40 rock) and Harp (indie rock) and JazzTimes (jazz and blues), the pool was already pretty shallow. If you are a music magazine trying to stay relevant with and ahead of its readers, you have a touch choice. Cover the pool that everyone else is covering and in the bargain make yourself just like your competitors, thus dilating your brand. Or you can cover people no one’s heard of before. It’s true that the Great Recession of 2008 has devastated ad sales for magazines across the board – even the mighty Conde Nast and its army of beauty and fashion glossies report ad pages down by 37 percent for September issues. But as far as music magazines are concerned, and as far as the effect of the dramatic shifts they have seen in the music industry for the past decade, perhaps the recession merely exposed ailments that were present all along.

The more music magazines scramble for the fruits of celebrity, the more irrelevant they may become. If so, they have incentive to stop the puff and do real journalism. A reasonable suggestion is imitating the best American music publication right now – National Public Radio. Its music website does what writers and critics should be doing. It sifts through the slush pile for the best in various styles. It offers in-depth interviews, features, and news on issues, trends, and people who are genuinely interesting (not just people like, say, the Jonas Brothers, who happen to be popular at Disney World). Perhaps tellingly, NPR doesn’t strive to brand itself according to a musical style. It just covers music, plain and simple. And its page brings readers what the web does best – live concerts, song samplers, and video. Its podcasts, particularly All Songs Considered, are among the most popular on the Internet.

Despite Mandel’s well-founded fears, JazzTimes is indeed rising from the dead. Earlier this month, it was acquired by Madavor Media, a Boston-based publisher of enthusiast periodicals on dolls, volleyball, figure skating, and golf. Whether it can remain solvent is an open question. According Mandel’s reporting on Jazz Beyond Jazz, Madavor says it will pay only half the promised compensation to contributors whose work has already been published. A resurrected JazzTimes, meanwhile, resumes next month, but over time, its critical integrity may be challenged by its new owner’s commitment to “enthusiasts,” a conflict with its own set of issues. A new owner was fine as a stopgap measure, but that doesn’t account for future headaches.

Maybe Quincy Jones, a former trumpeter for the legendary bandleader Lionel Hampton, is right. Maybe print is dead. And maybe that’s not such a bad thing after all. If Jones is able to revive Vibe, and make it as relevant today as it was when he founded it in 1993, let’s hope he makes room for his first and enduring love: jazz.