In his 1986 book about America, Baudrillard gets to Los Angeles and asks: “Where is the cinema?” His odd response: “It is all around you outside, all over the city, that marvelous, continuous performance of films and scenarios.” In France or the Netherlands, one walks out of a theater or gallery into a city that is the source text for the paintings and landscapes you have just seen. What Baudrillard discovered in his roundabout musing on Hollywood was a reversal of what he had become used to in Europe. In LA, it is the city that takes its cues from the cinema. If we want to figure out America we can’t start with our living spaces and think towards the cinema. Rather we have to begin there, in the continual flicker of our theaters, and realize that this is where society is born. Americans appear to live in screenscapes rather than actual landscapes.

For Baudrillard, this is a creepy thought, recasting our neighborhoods in the phantom hues of C.S. Lewis’ description of Purgatory in The Great Divorce. In his version of hell, the damned are free to construct any house at will, the catch being that they are only half-real. The restlessness inspired by this artificiality creates a cosmic urban sprawl, the houses of history’s oldest villains ending up light years from each other. Cinema can have an equally isolating and cheapening effect on the American conscience. But soon after America appeared, so did location intensive films like Linklater’s Slacker, Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho, and Jarmusch’s Night Train. This early wave of independent cinema broke the back of Baudrillard’s criticism, and by now we are accustomed to a kind of American cinema that is aware of the way Hollywood glosses over its tendency towards simulacra. What Baudrillard claims is very true in isolated Studio City cases, but it is by no means true of film that Americans have become increasingly aware of through our ever increasing exposure to independent and international cinema. I was reminded of this through a globetrotting theme that trailed my movie-going in 2008, one that responds to Baudrillard’s idea that the average American cinema is like a toxic leak in the public square.

Take for example Guerín’s recent In the City of Sylvia, the quiet story of a man on holiday in Strasbourg who thinks he has chanced upon a girl he met in a bar a few years ago. He follows her from a distance, through staged sets of minimalist urban compositions, until realizing that he is most probably mistaken. Much like the brisk pencil sketches his main character makes of this city’s many attractive café patrons, Guerín’s Strasbourg is beautiful and humane in its simplicity. His camera will linger for minutes on street corners and alleyways that his characters have already passed until their natural rhythms begin to appear. All the people-watching in the film, often obscured by mirrors, windows, and odd angles, begins to converge with Geurín’s preoccupation with the architecture of Strasbourg until the audience becomes part of its hum and throb. It is a voyeuristic experience, but one that keys us into the potential cities have for either alienating or embracing us. The film thrives on the pseudo-community experience of any Starbucks, and poses alternatives in its focus on the everyday spaces of Strasbourg.

A similar thing happens in Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Flight of the Red Balloon. In homage to the Lamorisse children’s classic, Hou’s film periodically shifts focus onto a red balloon bumbling its way across the boulevards and parks of Paris. Though the film is primarily about a young boy watching his single mother struggle to keep their family afloat, it is also about his fledgling experience of this beautiful city and the way his first memories of it have begun to form. There is the smoky café with a pinball machine his absent father taught him how to play, the sharp angles of graffitied streets he walks between school and home, the field trips to sunlit museums, peeling marionette stages in verdant gardens, and the different views from his apartment windows. Little Simon becomes a stand in for Hou’s obvious love of Parisian minutia, the red balloon at the same time a tour guide across the city and an emblem of the buoyancy of childhood memory. The way Hou frames this bittersweet slice of life with charming sweeps of Paris mimics the way particular cities define the structure of our memories.

Texture is perhaps the key word for Maddin’s My Winnipeg, a befuddling film that charts the history of his beloved home town across a series of memories both real and manufactured. The central image of the film is an imaginary subterranean river fork that lies beneath Winnipeg’s famous Red and Assiniboine River fork, a shape Maddin finds similar to his mother’s loins. In this “discovery,” Maddin finds out why he has never been able to move away from Winnipeg even though he has tried for many years. Winnipeg’s history and lore are so integral to Maddin’s coming-of-age, and woven into the fabric of his odd oeuvre, that he can’t conceive of disconnecting from it. The latter half of the film chronicles the real destruction of landmarks in downtown Winnipeg like a dirge. Though he can’t leave Winnipeg, he also can’t stop its slow demise. The absurdity of the film’s voiceover, and the collection of fables Maddin weaves around his description of the city, are the only responses he has left to the growing rubble. Like Hou’s film, My Winnipeg is bound up in a sense of love for a particular place, his surreal vision of Winnipeg emerging from an intimate knowledge of its sidewalks, streets, and buildings.

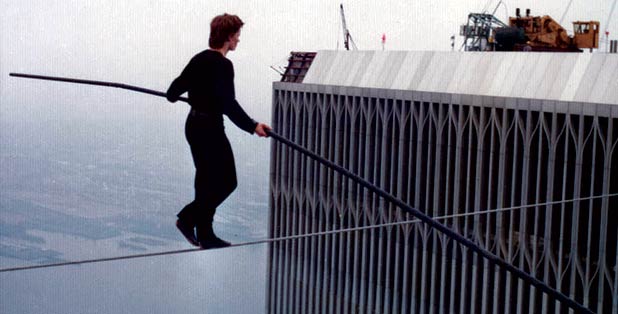

And then over all of these films about the way we relate to cities stretches Marsh’s Man on Wire. A documentary about Philippe Petit’s illegal tight-rope walk between the Twin Towers in 1974, the film is a parable for rethinking the way we look at our skylines. When we finally see Petit dancing across the wire in this rarified space between what were once the two largest buildings in the world, the impact of the film as a paean to our living spaces finally dawns. He has made these giant monuments to capitalism pylons in his own playground and the harried space of lower Manhattan a theater for his own monologue on play. Petit’s attitude towards cities as a stage for celebrating human ingenuity is only enhanced by the fact that Marsh never refers to 9/11 in the film. The documentary allows us to sidestep the awful memory and catch a glimpse of a 45 minute period during which the stark modernism of the Twin Towers had been far more eloquently reconfigured through Petit’s elaborate stunt.

In all of these films there is a looming presence of places: real streets, cafés, and bits of geographical lore that persist beyond the imagination of these storied tours. They are films intent on celebrating their chosen landscapes rather than using them to concoct the kind of infectious screenscapes Baudrillard discovered all over Hollywood. And though only one of these films actually takes place in an American city, they inform us nonetheless. We step out of theaters after films like this into St. Louis, Boston, Austin, or any other hazardously American city armed with ways to look at our neighborhoods and daily routines in similarly thoughtful ways. In the City of Sylvia and Flight of the Red Balloon train us to slow down and appreciate the fabric of our living spaces; masterful renditions of “smelling the roses.” Maddin’s film demonstrates how connected we are to our hometowns, which in a very real sense give birth to us. Man on Wire shows us how slight shifts in perspective can humanize places that have become so associated with the daily grind.

I like to think of films like this as an antidote to the dislocating tendency of Hollywood commerce and advertising described in America. In their celebration of particular places they train me to see wherever it is I live as a place to live and thrive rather than just a backdrop to my daily commute or a borough of the madding crowd. Like a master class in topophilia they tell us why our walk to and from the theater is just as valuable as our time in the theater itself. Or as experimental filmmaker Nathaniel Dorsky once quipped in a Village Voice interview: “Narrative film seems very clogged up, with almost no exceptions. It has no openness for me. I go to any narrative film, in recent years, and with almost every one, the lobby is more interesting than the film. Getting out of my car and walking to the theater is much more interesting, because at least I am alive in the present moment.” And, I would add, in a particular place.