“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women are merely players; they have their exits and their entrances, and one man in his time plays many parts.” As You Like It (Act II, Scene VII)

In an era before social media, the street was essential to visual art’s mass communication. The latest exhibition at Fort Worth, Texas’ Modern museum is Urban Theater: New York in the 1980s. Michael Auping, the Modern’s chief curator, remarked, “I titled it Urban Theater because, for me, the whole theme that runs through the ’80s is performance, staging and display.” The street territory outside the walls of galleries and esteemed museum collections was the new exhibition space of the ‘80s, facilitating free exposure, offering a starting place for artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. New York City provided the ideal urban landscape for artists to experiment in a kind of civic theater—where the world was the stage in the labyrinth of boulevards and subway stations.

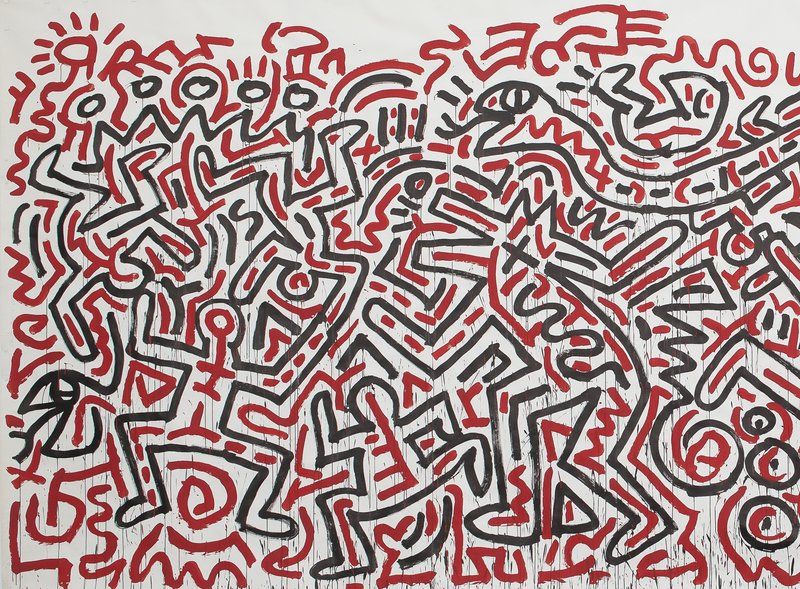

Considering the idea of the theater as central to the exhibition’s thesis, we might consider its featured performance a dazzling spectacle. Artists sought to contribute pieces in the most frequented, industrial, sterile, and average city-going spaces. Jenny Holzer’s truism’s lit up on billboards in Times Square as an alternate form of “advertising,” (i.e. Protect Me From What I Want, 1986). Haring’s spray-painted images in subway stations and Basquiat’s graffiti transformed the banal and quotidian into vehicles of activism. Photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe and Cindy Sherman both starred in and documented the unfolding spectacle of ‘80s New York, highlighting the disparity of racial and gender issues as a kind of art-in-action on an urban stage. Thus, Urban Theatre concerns both the civic space in and where works were created and also its actors, the particularized bodies which occupied and acted on the specified stage.

Which bodies can act in what places?

Michael Auping’s curation of Urban Theater groups work in two themes: sexual and racial equality and criticism of the market.

![Guerrilla Girls [no title], 1985–90 Screenprint on paper 280 x 710 mm Tate Collection](https://curator-magazine.ghost.io/content/images/www.curatormagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/guerilla.jpg)

Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex (1949) not only ignited the second-wave of feminism but also helped female artists have a deeper understanding of their identity within the male-dominated art world, as subject rather than object. According to Beauvoir, women were “separate but equal […] the very thing that Jim Crow did to black Americans. Egalitarian segregation served only to introduce the most extreme forms of discrimination.”[1] The Guerrilla Girls’ advertisements attend to both of these prejudices articulated by de Beauvoir on sexism and racism. Using mass-produced posters, the Guerrilla Girls posted statistics of galleries, art magazines and educational departments that denied hiring or exhibiting women and blacks. These anonymous artists combined wit with data, informing the public of discrimination after the Civil Rights and Woman’s Rights movements. One poster states: “What’s fashionable, prestigious and tax-deductible? Discriminating against women and non-white artists” (1987). The Guerrilla Girls utilized and critiqued other male contemporaries manipulating a Warhol-esque style in format, even at times superimposing Velvet Underground images. The exhibition wall, showing their posters operates on a meta-level, provokes the viewer to bring the exhibition at hand under the same scrutiny.

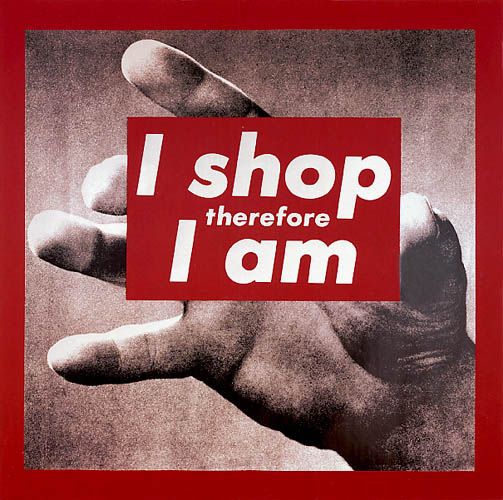

Another key artist in Urban Theater is Barbara Kruger, who engages economic concerns as well as women’s issues. Her I Shop Therefore I am (1987) is a cheeky play on Descartes’ Cogito ergo sum. As a former chief designer for the fashion magazine Maidemoiselle (where she inherited her graphic design talents), she learned the forms of advertising and propaganda, which were specifically marketed towards women. In the black and white image of a female hand holding what seems to be a superimposed maxim on a credit card, Kruger uncovers the power of media to socially construct gender identity, as critic Arthur Danto relates, “upon something frivolous in being one whose essence is shopping.”[2] Her poignant critique of America’s nihilistic consumerism exposes cultural practices that not only constructed women’s sense of identity, but conversely effectuated women’s oppression.

At first glance, Sherrie Levine’s After Man Ray #3 La Fortune (1990) appears to be a nondescript pool table isolated in an exhibition wing. However, a closer look reveals that there are neither cue sticks nor pocket holes. Taking a memorable staple of the men’s billiard room, Levine suggests that the sculpture’s structure is metaphorical of men and women’s relationship to each other, particularly in the art world. Women are the curved legs, supporting the table on which men play in order to sink their balls into the corresponding holes, ahem, pockets. Since there are no pockets in this billiard table, Levine insinuates this paradigm is “an impossible game” due to her intentional yet “inoperable construction.” What originally might be mistaken in the gallery as a pastime apparatus is rather totemic of Urban Theater in its male-female thesis during the 1980s.

Cindy Sherman, on the other hand, plays upon the viewer’s gaze or participation in her images, as both the subject and director of her photographs (Untitled Film Stills, 1977). She is not interested in coiffing and primping to conform to certain stereotypes, nor does she provide the viewer a contextual narrative through which to interpret her images. In this case, as Michael Freid suggests, the film stills are “anti-theatrical.”[3] She wryly inverts the gaze back on the viewer and questions his/her assumptions and projections on her images, critiquing voyeurism, the male gaze and aesthetic judgments. In this way, the modality of her images resemble the economy of the icon. The images ask us how we are looking at her and seek to correct our vision by catechizing our gaze.

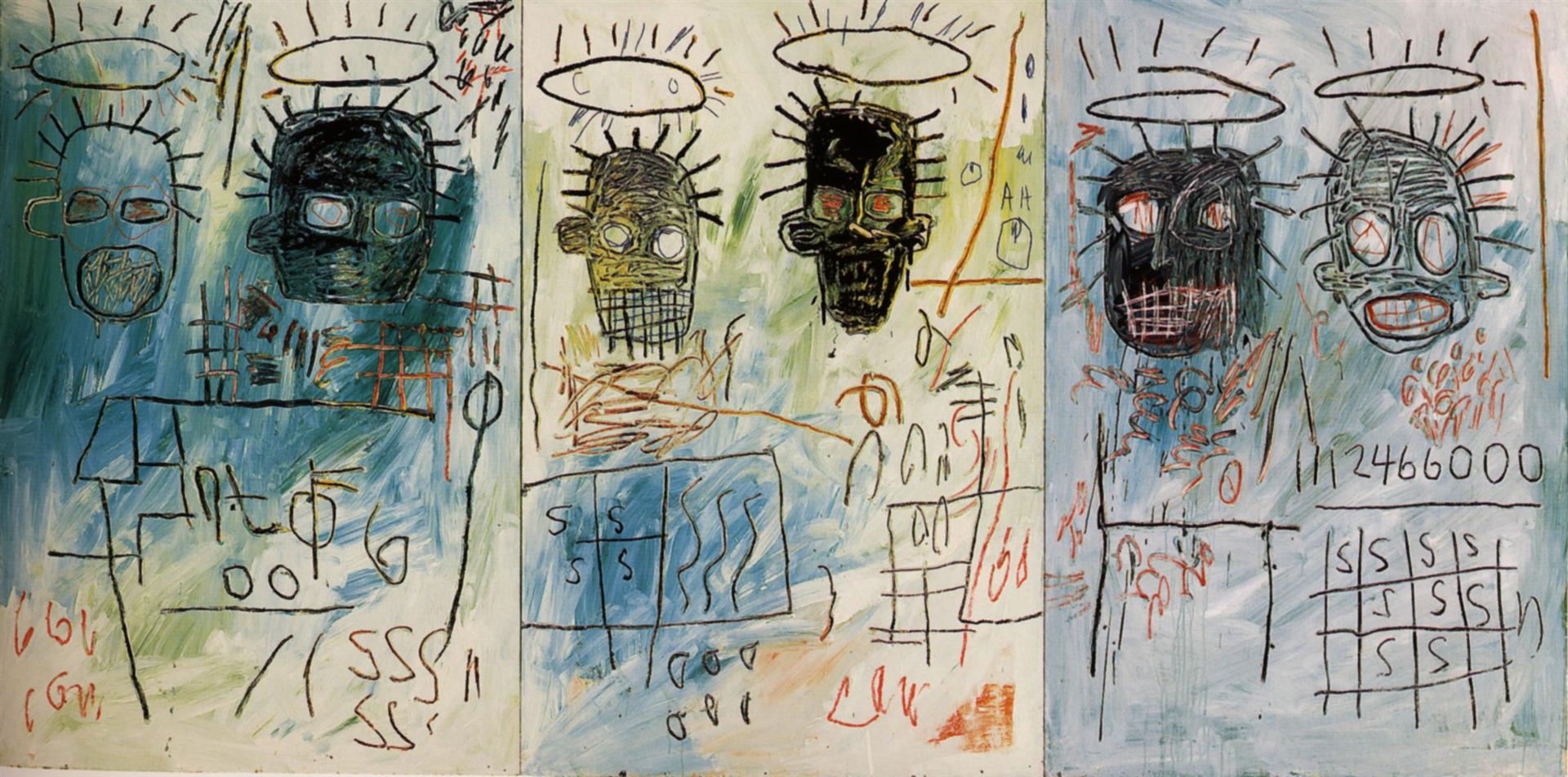

Urban Theater takes into consideration the economic favorability of ‘80s as both ideal for the marketability of art, while reminding us that consumerist demands can be a detriment to its creation. Art collectors and dealers alike desired paintings as financial investments in a booming market. Enter Jean-Michel Basquiat. The “radiant child” had humble beginnings through street painting activism, signed as SAMO© (same old sh*t), a graffiti informed by a political critique of oppressive market systems. We might be reminded both of Cy Twombly in his mixture of drawing and writing combined with painting and Jean Debuffet’s primitive art brut. Yet his subject is far darker than Twombly’s childlike scribbles in lllium. Basquiat’s pastiche penetrates the horrors of the outsider and the injustices in human history. His Six Crimee (1982) in this exhibition depicts six black heads with halos floating above them on a background of vibrant malachite green, a color often used by Quattrocento artists like Cimabue in portraying saints. Basquiat gives us a vision of black martyrs, who have perished at the cost of systemic brokenness—a system, W.E.B. DuBois wrote, that was not designed to protect blacks in the first place.

Quite paradoxically, the theater of the ‘80s in New York also contained work antithetical to Basquiat’s scathing critiques of bloated economies. Jeff Koons, the high priest of factory-produced mass culture-as-high-art for a consumerist market became very successful. Following the natural progression of art’s evolution after Duchamp’s Fountain urinal (1917) and Warhol’s Campbell Soup Cans (1962), he conflates a bourgeoisie taste for the sentimental and the kitsch, seen in this exhibit as Buster Keaton (1988). In many ways Koons sees himself as the public’s savoir of embracing secretly repressed bad taste. “The imperative” he states, “is to be yourself and don’t pretend to be someone else whom you believe superior to yourself. Your tastes are all right as they are […] bad taste is as good as taste gets if it is yours.”[4] One can’t help noticing that Koons’ critiques about taste and class are ironically what have made him one of the world’s wealthiest living artists. And yet there is something annoyingly democratic about its intellectual accessibility and intentional self-deprecation of artistic elitism. One does not have to be educated in art to comprehend his subject matter; in fact, one might momentarily mistake being in a souvenir shop instead of a museum.

Auping curated the images in Urban Theater as moving parts to a story, creating a photographic tableau in the museum. But how much do these activism-charged pieces evolve in context of a museum?

The museum’s sterile, peaceful, and tidy interior decontextualize these artifacts from their dynamic involvement with their environment—a dangerous yet thrilling 1980s New York City. The gritty and edgy components of these art works lack their initial subversive and inflammatory qualities. Isn’t housing within the museum the ‘art of the streets’ with its egalitarian ‘art for everyone’s sake’ an ironic contradiction? Their rigors of unmasking are downplayed, as spectacle divorced from theater? Reconstituting the works within the museum is a different kind of theater belonging to both the curator and the visitor, contingent on individual experience.

The concept of the cinematic tableau helps in reuniting spectacle and theater together in this exhibit. In conjunction with the Urban Theater, Auping organized the Lone Star Film Festival to host a paneled conversation in-house with Julian Schnabel, screening all three of his films, Basquiat, Before Night Falls, and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly at the Modern Museum. As a painter and filmmaker, Schnabel is a common thread synthesizing the Urban Theater era, painting alongside Basquiat and Warhol, as well as filming their stories. The interview with Schnabel was lively and disarmingly direct, considering the trio of his vivid films. Each of his protagonists are marginalized or overcoming a significant cultural stereotype as an exilic: racially distinct, homosexual, or handicapped. It became quickly apparent in the conversation that the components of textural complexity and poetic sensibility were critical in Schnabel’s visual art and cinematic compositions. He spoke of his influence from Tarkovsky where “film is an accumulation of moments like paintings.” The difficulty of navigating the exhibition’s decontextualized artworks from the city of New York is mitigated by screening Schnabel’s Before Night Falls within the museum’s theater after the interview. Together, artist/director, curator and audience collectively encountered a movie through the medium and the stage for which it was intended. Thus, Schnabel’s film contributes an art form to the exhibition that is not stripped from its original context and reimagines the medium of art making for a larger audience.

New York City provided the ideal urban landscape for artists to experiment, to engage in a kind of civic theater— where the world was the stage. Unfortunately, many artists had their exits prematurely in this period due to accidental drug overdose and AIDS, among other things. Warhol, Basquiat and Haring are among the talented acts that faded too soon.

[1] DeBeauvoir, Simone. The Second Sex, 1949. p.12.

[2] Danto, Arthur. Unnatural Wonders: Essays from the Gap Between Art and Life, 2007. pp.64

[3] Freid, Michael. Why Photography Matters as Art Like Never Before, 2008.

[4] Danto, 291.

*Featured Image: Keith Haring’s Red (1982-1984), part of the the exhibit Urban Theater: New York Art in the 1980s, on display at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. The work is goauche and ink on paper, 106 3/4 inches by 274 inches. Photo: Courtesy: Gladstone Gallery, New York, and Brussels Haring Foundation.