Having dabbled in music composition, graphic design, and writing fiction, I found in myself a confusing network of interests and an alarming readiness to feign expertise in a new medium. I realized that I had become a jack of all trades (and the rest of the cliché)—a fool who enjoys sensual and creative stimulation but can’t bring himself to commit to any one discipline. But now, after recovering from that intense addiction to creative practice, I’ve begun to understand a larger definition of space—one that functions not only in art per se but in the creative process and in real life.

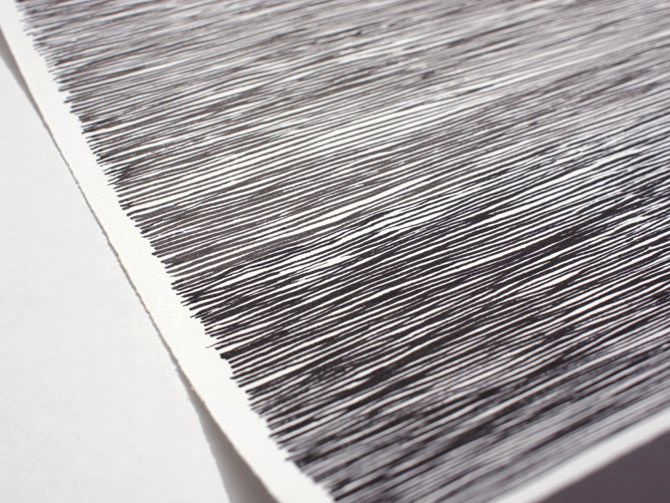

I had never thought about space until I started taking graphic design classes. When I heard the same crits over and over and studied the successful examples the teachers pointed out, I began to perceive the visual silence around the subject, around what we consider at first glance to be The Good Stuff. Comparing this to the student work around me, I realized that The Good Stuff suffers in oversaturation without a context of visual silence.

I started thinking about this in relation to music. I thought about things I had written and things I had analyzed. I questioned why I loved or hated certain pieces. I found that what I disliked about a lot of mainstream genre music was its low range of both vertical and durational space—that is, a tendency toward sameness in how big and how complex. Then I realized that that’s what I like about Oceansize and Fleet Foxes and Bach: Each gives me, in its own way, a constant interplay between The Good Stuff and some form of silence. Bach’s music especially displays this use of space. He is a master of the unstated, and his unstatement shines in his solo cello suites. He uses the leaping of a single melodic line to sketch the forms of larger harmonies, giving you the sense of a harmonic context which you aren’t actually hearing. Your ear, rather than Bach, assembles the outlines and suggestions into something larger.

While I was still a music student, I never worked toward unstatement. Instead, I pushed myself obsessively toward Good Sounds. I looked for one grandiose chord, something with the towering suggestion of infinite color. I created some good chords, but I never found The Chord of Everything. Eventually I gave up. I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in composition and a general bitterness toward academia, a resolution not to perpetuate the cycle of get-degree-to-teach-at-university. Feeling smart and rebellious, I abandoned that track and turned to my neglected writing project, the latest novel in a long line of work that wasn’t worth sharing with people. And I resolved to become a Novelist, capital N.

I tried it for a while. I grew a lot as a writer, but then I started thinking about raising a family and being a breadwinner. My creative potential was still high, but my income potential looked like silence; so I scrambled to fill that silence. I started another degree, this one in graphic design. Rather than leaving the white space in my life alone, I tried to slather it with The Good Stuff. One and three-quarters semesters later, I dropped out, overworked and plagued with anxiety attacks. I had not yet learned the function of silence, of uncertainty.

I suppose any creative discipline, including the living of life, is a constant relearning. Before I tried graphic design, I thought I knew novelizing; I didn’t. Now, no longer cutting cardstock with a razor, I started cutting words with a razor. I relearned and relearned, but I knew I had not yet found my voice. It was not until I grappled with William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury that I began to realize the meaning of white space in Story. With my clinical descriptions of roads and trees, feelings and thoughts, I was shouting at my imagined reader, “This is my story! Don’t you like it?” But Faulkner showed me another way. He insisted, with his obtuseness, that I pay attention and stumble toward some form of reality that even he might not know. He never preached Story; he offered it, and he refused to hold my hand.

I resolved to do likewise in my novel. I rewrote the whole thing. I worked obsessively, editing first thing every morning and reading last thing every night to absorb another writer’s brilliance and do it all again the next day. But the anxiety attacks came back. In purging myself of other people’s demands and turning inward to my great purpose as Novelist, I wasn’t curing myself; rather, I was oversaturating my mind and emotions with The Good Stuff. Insanity was blossoming in the noise, and it was my fault. For once, I couldn’t blame the bosses or the professors, for I had become my own professor; and I was a tyrant.

At the same time, I couldn’t say no to music. I was still in a band with my brother. I was still hauling amps at the wrong hours of the night and still adoring the imago of our rich and varied material. Oh, we had certainly stumbled upon the law of silence. Our stuff was loud and then quiet, mechanical and then melodic. It was really good. But our well-composed music bore no reflection in my disorderly life.

All of this began to look like some weird analog to the concept of Signal Versus Noise—except that the meat of artwork, The Good Stuff, wasn’t the signal; it was the noise. The signal that I so desperately needed could only be found in the silence that I refused to practice.

That was when I realized that the creative process itself is an artwork, sheltering what we call art, nested within the larger artwork of life. This three-tiered fractal structure of art within art within art, of wheels within wheels, was collapsing around me. I was not balancing the outermost medium of creativity—my life itself, my mental and emotional health—with crucial white space. My head was crammed with obsession over what I wanted to accomplish and the corollary fear of failure. I may have written The Good Stuff with my pen, but with my life I was writing noise, an insidious scrambling toward infinity. And it was becoming clear that I was not meant to be infinite.

That’s where I am now. Not infinite, living sometimes in the sounds and sometimes in the silence. The other night I lay in bed at 4:30 a.m. wishing that Sudafed hadn’t made me antsy—and that, if it was going to do so, it would at least clear my nose so I could sleep. Exhausted, suffering this for many nights in a row, I asked God with sincere and childish tears where He was. I heard only silence, and I cried some more.

But a thought kept nagging: maybe this God is balancing his artwork with white space.