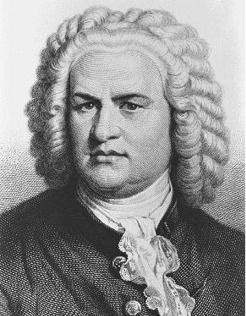

It is not uncommon in our culture to find the intellect pitted against feeling, or careful, nuanced thought against intuition and common sense. The United States has a long history of populist sentiments and suspicion of elitist intellectuals. Politicians today divide the country between the cultural elite and “real Americans” (one party disparges the cultural elite, the other the corporate elite). Some popular musicians deliberately avoid formal training for fear that it will taint their natural creativity. The abstract and academic are seen as artificial, as if learning somehow interferes with the expression of one’s natural self. This dichotomy between heart and mind did not exist for Johann Sebastian Bach, whose music is both intellectually dense and emotionally powerful.

Bach lived at a pivotal time in Western history. His lifespan (1685 – 1750) coincides with the heyday of the Enlightenment, a movement whose forces continue to shape our society today. Cultural trends were changing during his later years. As a reaction to baroque complexity, classicism sought structural clarity across many disciplines, from architecture to music. Classical influences in music produced the galant style, where simple melody and accompaniment textures replaced the rich, complex layering of many horizontal melodies known as counterpoint, a musical art dating back to the 12th century in the ars antiqua. Music written in the galant style was considered to be more natural and accessible. The complex and weighty was out, while the simple and frivolous was in. This new music, with its simplified harmonies (primarily emphasizing the tonic and dominant) and light, graceful melodies, had no higher aim than to please the audience and titillate the ear of the casual listener.

Bach considered the new style vacuous and continued on his own path, contrary to the fashion of his day. This brought scathing criticism (which sometimes stooped to outright mockery) from prominent musical commentators such as his former student, Johann Adolf Scheibe, who called Bach’s denser style of music “turgid and confused” and Bach himself an uneducated amateur. Even his own sons favored the new galant style, though they were more polite in expressing their opinions of their father’s music (though in his later years, Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach returned to the more substantial style of his father).

Bach never wrote a verbal rebuttal to Scheibe’s attacks. The compositions of the last decade or so of his life, however, are a powerful refutation of his contemporaries and critics. Bach set out to show that music could be both intellectually satisfying and deeply moving. Clavierübung III (1739), Clavierübung IV, better known as The Goldberg Variations (1741), The Musical Offering (1747), the Canonic Variations on “Vom Himmel Hoch, da komm’ ich her” (1747), the Mass in b minor (1749), The Art of Fugue (1745-1750), and “Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich hiermit” (1750) took contrapuntal art to levels unmatched before or since, and yet they are also some of the most profoundly beautiful compositions ever written. For J.S. Bach, those two things were not mutually exclusive, but were in fact organically linked.

In his book, Evening in the Palace of Reason, James R. Gaines describes this union of soul and mind in Bach’s final composition, Vor deinen Thron, tret’ ich hiermit (Before Thy throne I now appear), said to be composed via dictation from his deathbed:

Now, sightless, he set about composing a quietly eloquent variation in counterpoint for this text, Vor deinen Thron. The result was one of the most beautiful chorales he ever wrote (BWV 668). Set to the medieval integer valor–the tempo that of the human heart, each bar the length of one deep breath in and out–it is also in every other way a work of human scale and sympathy. Bach manages the remarkable feat of making each of the melody’s four sections into its own fugue, each time using the inverse of the subject as his countersubject, and as the work proceeds the counterpoint becomes ever more complex, “moving ever farther from the body into the domain of the spirit,” as David Yearsley puts it. “It is in this way a representation of the act of dying.” And yet even as it unfolds as a tour de force of the most intellectually demanding contrapuntal art, there is no aesthetic sacrifice to this technical achievement, no hint of “eye music.” From beginning to end, “Vor deinen Thron” is a song of hope and courage, with all the elaborate ornamentation of the earlier version stripped away.

Listen to the chorale:

Much of the thinking of our own culture assumes a division between the sophisticated and the genuine, the rational and the senusal, thinking and feeling. Ironically, this strand of anti-intellectualism can be partly traced back to the Enlightenment. In 18th century Scotland, around the time when musical tastes were shifting from the complexities of the baroque era (culminated in the music of J.S. Bach) to the galant style of the classical era, a thinker named Thomas Reid was expounding an epistemological framework called Common Sense Realism. As historian George Marsden notes,

Common Sense Realism said that the human mind was so constructed that we can know the real world directly. Some philosophers, particularly those following John Locke, had made our knowledge seem more complicated by interposing “ideas” between us and the real world. These ideas, they said, were the intermediate objects of our thought; hence we do not apprehend external things directly, but only through ideas of them in our minds.2

Over time, Common Sense Realism had a tendency to devalue nuanced thinking – after all, if truth is directly available to our intuition, what need is there for careful, rigorous thought? This leads to simplistic thinking, to trusting one’s gut in place of disciplined thinking in working through complex problems. Good instincts are then valued more than formal training.

In the late 18th century, a young nation was emerging in the New World which proved to be fertile soil for the ideas of Thomas Reid. Common Sense Realism fit nicely with our democratic, anti-elitist sentiments, and its populist effects are still strongly felt today. It is so ingrained in our culture that it usually goes unnoticed, such that most Americans would claim that they don’t have a philosophy but just use common sense. This mode of thinking and the galant style of the 18th century classical music both share the populist notion that everything should be directly accessible to the intuition, regardless of any cultivation of the mind through formal training.

We could benefit from studying the work of J.S. Bach and letting his statement of principle embodied in his late works challenge our assumptions that the emotional and the intellectual are mutually exclusive. It is ultimately a matter of unifying not just two abstract concepts, but of unifying the heart and mind of the inner person.

Footnotes:

1. James R. Gaines, Evening in the Palace of Reason: Bach Meets Frederick the Great in the Age of Enlightenment (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005), 251-252.

2. George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism 1870-1925 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 14-15.