Here I am, writer at the desk, remembering. My memory summons up a homesick afternoon that I must write about, and now the picture appears. There I am, twenty-three, stretched out on the cool hardwood floor of my bedroom like a sad snow angel, listening to…

Eels. Electro-Shock Blues. I’m sure of it. I was a hip, sad indie snow angel at twenty-three, wasn’t I? And wouldn’t the title Electro-Shock Blues perfectly convey to the reader just how distraught I felt that afternoon?

Ah, writer. How quickly memory and wishes intertwine. Remember closely, for a moment. Admit that in fall 2005, when you were twenty-three, you had only ever heard one Eels song. Recall that when you wanted a soundtrack for your sad mood, what you reached for then would most certainly have been Counting Crows: I need a phone call. I need a raincoat. I need.

So, here I am, rewriting. Much as I wish I had listened to something with a little more cultural cache, I must present the truth. And, in this case, the truth illustrates what I was like at that time in my life much more deftly than my superimposed hipness does.

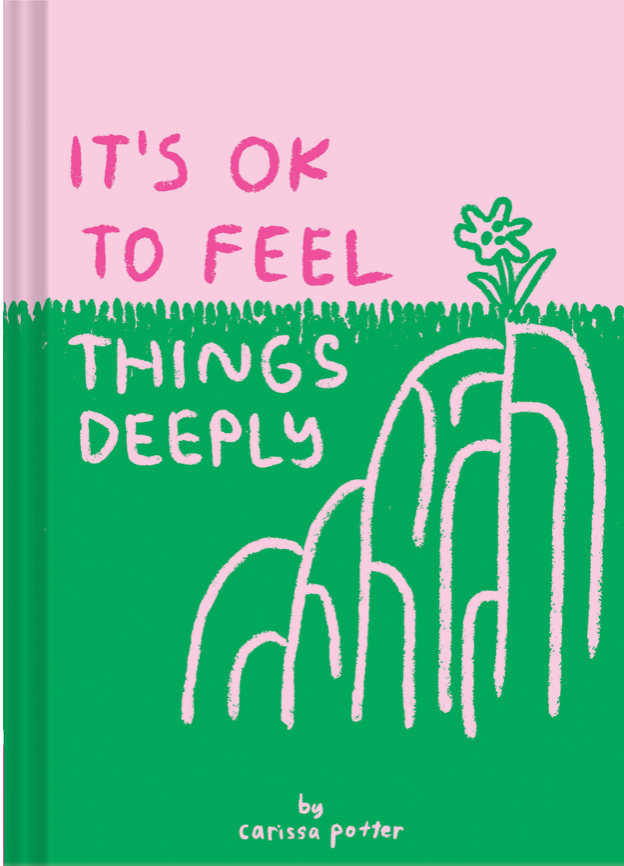

When I write Creative Nonfiction, I must write what is, to the best of my knowledge, true–or signal to the reader that I’m taking liberties. But the complexity of what truth means in this genre is inherent even in the name itself. Tell someone your primary genre is Creative Nonfiction and you’ve primed them for a joke. You’re sure to meet a smirk and the question– “Isn’t that what all journalism is? Aren’t journalists creative with their ‘facts’?” Even though the name itself seems to call “nonfiction” into question, what is creative about Creative Nonfiction is the merger of truth with imagination, fact with story-telling, the objective with the personal.

There have been at least two currents in Creative Nonfiction for a very long time. One fork of the river bends toward writing emotionally true or artistically rich prose, even if this relies more on imagination than fact. The other bends toward what is factual, verifiable, and personally honest, while still craving emotional authenticity and artistic innovation.

Scandals have plagued those who identify with the first trend. Several memoirs, like James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces, and a best-selling journalistic autobiography, Three Cups of Tea, have turned out to include troubling fabrications.

For those who–like me–identify with the second current, complexities abound. For one thing, this is a genre mainly interested in the past, and exploring one’s own past honestly is difficult even for those who want to present it without adding or embellishing. It’s obvious that memory tricks and eludes us; what makes memory even more slippery is that the more we think about a specific past event, the less reliable our memory of it becomes. For memoirists, who must access the same memory again and again in order to compose, the first experience of that event slips further away with every writing session.

For another thing, one of the gifts that postmodernism has given us has been to show us the need to be humble about our perspective. What we perceive has been colored by our human fallibility.

And yet, these complexities can be handled with integrity because when the reader cracks open a creative nonfiction book or scrolls down the page of a creative nonfiction essay, he or she expects that memory is an imperfect faculty. The reader also expects the author to use it honestly, without knowingly adding or distorting. The reader expects that even the most ho-hum nonfiction will also be shaped by its perspective. In the most creative works, facts will be shaped in innovative ways, but in works that commit to truth, the facts will simultaneously shape the narrative.

When the line between truth and imagination blurs, the writer does the reader and the genre a great service by signalling that the conventions have shifted. Peter Trachtenberg is wonderful here:

My position is that if the facts are your own, you have a license to play with them in various ways, as long as you give the reader some indication of what you’re doing. Dogs signal that they’re about to play by smacking the ground with their forepaws. I’m only suggesting that memoirists do what dogs do. Otherwise somebody may get bitten. Or mistake a nip for a bite.

Of course, clamping down on genre boundaries may seem too much like the landlord who pounds on the apartment door just when the party is getting interesting. John D’Agata, whose lyric essays I love and have referenced elsewhere, has recently come under fire for writing a book that sounds like journalism, yet is intentionally loose with facts. D’Agata said in a PRI interview, “I think that we have to be fooled before we are really able to wonder. So philosophically my issue is that we’re not allowing an entire genre – nonfiction – to have that kind of a relationship with the reader. And that’s for me, as an artist, that’s problematic.”

Yet truth and honesty can be limits that aid, rather than prohibit, creativity.

Consider this snippet from a recent Wired article:

One of the many paradoxes of human creativity is that it seems to benefit from constraints. Although we imagine the imagination as requiring total freedom, the reality of the creative process is that it’s often entangled with strict conventions and formal requirements…. symphonies have four movements; plays have five acts…. The brain is a neural tangle of near infinite possibility, which means that it spends a lot of time and energy choosing what not to notice.

As David Foster Wallace noted in his introduction to The Best American Essays 2007, when one writes nonfiction, one is immersed in an “abyss of Total Noise, the seething static of every particular thing and experience.” Could writers in this genre hone the noise into intelligibility through constraining themselves to what is true? Could close adherence to facts, honest memory, and reader-signalling be constraints that benefit this genre’s creativity?

Such honing not only creates greater trust between the reader and writer, but should allow the genre to flourish so that truth, like form poetry, will give writers just the limits necessary to write their best nonfiction. The narrow doorway opens onto a large and freeing vista where we can be overcome by what is solidly there in the world.

If we think we have to be fooled before we are really able to wonder, maybe we our concept of truth is too small. Let’s revive the possibility that the truth is larger and more fascinating than we have imagined. Let’s consider that it might leave us in awe, or horror, or even wonder of the things we write and read.