In Pilates and various meditative disciplines, I’m told to look inward and focus my being—to “center” myself. While this works on a physical level, helping to tame breathing and related symptoms, it doesn’t work for my soul. When I look inward, the magnificent bastion of self I’m supposed to find simply isn’t there. I get nothing but a void.

When in pursuit of the elusive self, the cross-country road trip, the career switch, the sudden taking up of painting, all get invoked. But what is the self? I’m not even sure it exists outside our neurochemical construction of it. Perhaps it’s nothing but an accumulation of remembered attitudes toward remembered things. Memories slip. Language, the building block of memory, stumbles under the burden of nailing down meaning. Hence, “each moment is a new and shocking valuation of all we have been,” as T. S. Eliot writes in Four Quartets. As the self seeks to know itself better, it can study nothing but its own reflexive construction of what it thinks it is. The very words it uses are, at each moment, its own words.

Our generation often shatters on the rocks of this search. Driving forward under waves of find yourself, find yourself, people of our generation lose more and more of their vitality and peace in the frantic search for vitality and peace. Isadore the Priest spoke to our generation when he supposedly said, “of all evil suggestions, the most terrible is the prompting to follow your own heart.” And yet the endless breeding of new blogs and tumblrs and iPhone covers declares that the only way forward is increasing differentiation and uniqueness. But as the media phenomena through which our generation seeks uniqueness reveal more and more of their self-construction, the burden to make the self falls entirely on the self. Only you can build your personal brand, and only machine-enabled experiences can tell you how to do it. You inform machine processes, and they inform your self-construction.

So the self grows with the machines it creates (which also recreate it). The question of this generation is, what kind of self will emerge from an increasingly symbiotic relationship with increasingly powerful and amorphous machines? We are already beginning to see an answer: a mindset of networked simultaneity has begun to displace the sequential approach to activity which the modern era curated (and which curated the modern era). The modern self worked in discrete processes and in environments with clear limits. It orbited goals with clear courses and gravities. In other words, the modern self was centered. The hypermodern self, today’s self, works with fluid processes in unbounded environments, uncovering and continually adapting. In other words, the hypermodern self is decentered.

Like the technological relationships which engender it, the decentered self is amorphous. It is ready to switch media at a moment’s notice, following the latest notification. It does not categorize things as clearly as the centered self did because it has no need to. Relational technology performs the categorization and determines what to present and when to present it. The de-centered self is totally networked, perpetually enervated, participating in this emergent common mind that is larger and louder than any one of us. The decentered self googles everything and uses apps to get its chores done.

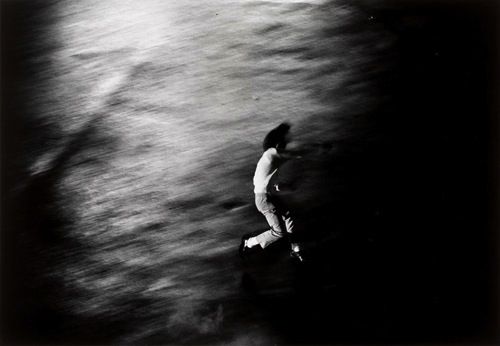

In something like a perpetual panic attack, the decentered self lives an amped life, staying on top of the ever-evolving sum of popular knowledge, culture, and technology, predicating its sense of legitimacy on its alignment with the ever-expanding latest and greatest. The newest operating system, newest iPhone or Apple gadget, it has to have them all. Without them, the decentered self is simply a castoff piece of debris from the mad hayride of technological advance. It fears this fall on stony ground more than anything else: to be lost and disoriented, dis-networked and dis-mediated, unseated from the careening carriage of change.

These two selves exist easily inside us because we live in a transition between two great ages of history. We are abolishing the centered self, but it is not yet abolished. Some of us are still trying to achieve the American Dream, and though the true promise of the Dream was always dead, this strain of meaning-making has hardly disappeared from the collective psyche. But the discovery of “meaning” within personal wealth and disregard for the community is fundamentally modern. Like all things modern, it values certain separations: nation from nation, public from private, middle-class castle from middle-class castle. Because this narrative relies heavily on these separations, it will not survive the transition; for the technology of the transition, our enervation by the internet, obliterates separations of this nature while introducing new separations.

The disintegration of all psychological barriers, the networking of all physical and psychological realities, means the decentered self coexists with the centered self. The decentered self emerges naturally in reaction to the failure of the narrative that created the centered self. Sensitive to the boundaries which the modern age enforced, the decentered self experiences those boundaries like a cultural punch in the face. The decentered self seeks solace from the terror of modern boundaries in endlessly branching connections across discourse spaces. Where the centered self sought a localized heaven on earth through personal advance within capitalism, the decentered self seeks heaven across network in a growing resume of connective technological experiences.

In his brilliant essay “Buffered and Porous Selves,” Charles Taylor describes the pre-modern consciousness as “porous.” He means that the pre-modern self believed that its experience flowed into and out of it. This stands in stark contrast to the modern self, which Taylor calls “buffered.” In this terminology, he captures the ubiquitous sense of separation which characterizes the modern self.

His idea of the porous self relates in two ways to the decentered self. First, Taylor’s porous self—a self at one with the phenomena around it—is that which the decentered self seeks to become in its search for heaven-across-network. Yet since the decentered self seeks this experience through a fundamentally buffering phenomenon (personal connective technology), it will never achieve the return to human connective roots that it desires without eroding the meaning of connective experience in the process.

Second, I believe Taylor’s porous self is what we should strive for—a consciousness that participates in the world processes around it and even participates in the Divine. Owen Barfield addresses this idea of participation in his brilliant book Saving The Appearances. He writes, “Participation is the extra-sensory relation between man and the phenomena… actual participation is… as much a fact in our case as in that of primitive man. But we have also seen that we are unaware, whereas the primitive mind is aware of it.” [1] For Barfield, participation is that which Taylor’s porous self practiced in the pre-modern era. Participation was the flowing-into-and-out-of which the premodern self saw occurring between itself and its world. In an essay with the Other Journal, I discussed the connection of Barfield’s idea of participation through participatory technology—devices and platforms claiming to connect us with friends and family. In truth, these technological phenomena quietly buffer our experience of other humans at a financial gain for the corporation disseminating the technology. While the decentered self rightly seeks the participation which the modern era lacked, it defeats its search by seeking this participation in technology that encourages the spatial isolation of users.

Modernity has taught us that separation is hell. We have begun to long for a breakdown of separations, and now we seek that breakdown in decentered connective technology. In phenomena as diverse as Facebook, Uber, and Skype, we grope back towards a participatory, porous sense of self. But what does this return entail? And is it authentic? I believe it is not what we’re looking for. The true object of our desire is far more radical. We live in a war zone between centered and decentered value systems. In this cultural climate, the intentional construction of a porous self with many branching online connections is not radical. However, the intentional creation of a non-technologically mediated porous self is radical. This choice means seeking connectivity not in technologically networked experience, but with people, in person, and in relationship to the Divine. One can only make this move after recognizing the failure of both the centered and decentered models of self, and this double failure leaves the constructed self with a deep and overwhelming sadness. This radical connectivity is grace. It is the only solution.

The arts are always the front lines of cultural development, and grace has begun to emerge there. As Piet Mondrian said it in another context in the 20th century, “art had to find a solution.” Art is still finding solutions. Makoto Fujimura’s paintings rest in a static, transcendent place of grace. Forest Management’s ambient drone enables peace and real downtime. Matthew Anderson’s newest record fuses sorrow and beauty relentlessly. All these artists grope for true participation. Their works lack personal rage and political agendas. In place of “words, words… led out to battle against other words,” [2] these artworks proclaim something from beyond the constructing self.

To gaze on this something other is to be truly ex-centered—truly eccentric. One is centered not inwardly on one’s private fortress, not outwardly on expanding noise, but on a singular moment of grace. The true eccentric need not flesh out a full theology of who and what this grace implies, for she understands that if it is grace, if it is extrinsically sourced by no effort of hers, it will defy her ready-made cognitive boxes anyway. Grace manifests in art that’s content with the incongruities, the uncertainties, and the dissonant implications of the numinous. These things drive so many people away from the arts and from faith, yet they suggest to the true eccentric that she has found the interwoven pain and beauty of real truth. No longer looking inward to emptiness nor outward along networked, self-augmenting noise, the true eccentric fixes her gaze, as best she can, on grace—on something wholly other—on the numinous. Where logic breaks down, grace begins. Though every one of us needs grace, none of us can demand it; we can only give it.

[1] Barfield, Owen. Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry (New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975), 40.[2] Lewis, C. S. Till We Have Faces. (New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985), 308.

Featured Image: Untitled, from the series Protest, Tokyo, by Shōmei Tōmatsu, 1969, printed later, photograph | gelatin silver print

Source: http://www.sfmoma.org/explore/collection/artwork/29652#ixzz3fWLTQEGl

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art