Today begins National Poetry Month. Like Love Day, it’s a made-up thing that is warm and fuzzy and a little lame. I love it. It comes from the earnest belief that poetry needs to be celebrated at the national level, lest we forget its importance in knitting all of America together. In Percy Shelley’s famous phrase, “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” something that sounds nice and all, but really, we’ve all seen lately how powerless legislators are in the face of a rising tyranny. I teach for a living. What change is like the change of these past ten years, as the “hopeless little screens” pulsing in my students’ pockets, in mine, demand and receive increasing fealty? Poetry doesn’t stand a chance.

NaPoMo, as it must henceforth be called, is scheduled every April to serve an allusion only poets (many) or readers of poetry (a few more than many) will get. If you’re not sure of the reference, I won’t spoil it for you. The rest of you may enjoy a cup of hot cocoa in knowing satisfaction.

The best part of the month is the vows people make to write a poem a day, a vow I have made in the past and am making again now, publicly, to all of you. Searching Twitter for “National Poetry Month” brings dozens if not hundreds of tweets by excited poets inviting readers to follow them on Instagram and Tumblr and, uh, Twitter to read new compositions each day of the month. I’d like to see this as hopeful. But the wisest suspect that, like any special occasion, the promise is bigger than the payoff:

National poetry month, (honey be good to me).

— Amber McBride (@msambsnicole) April 1, 2019

Ahh, but it won’t be, friend. Not entirely.

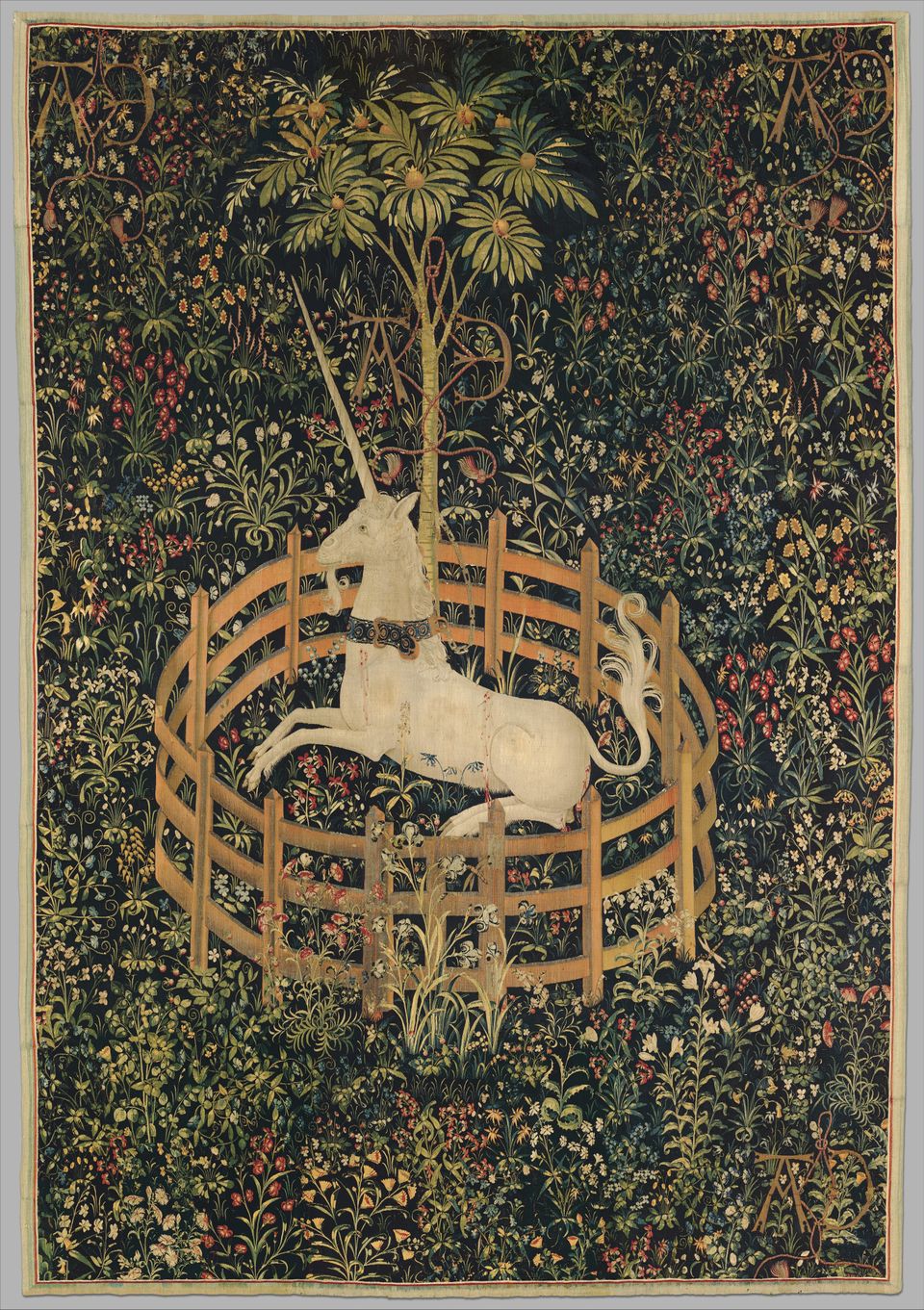

Why won’t it? Well, for one, writing is hard. In the back of our minds we can hear John Keats telling us “That if poetry comes not as naturally as the leaves to a tree, it had better not come at all.” Talk about pressure. Leaves come to a tree in the spring (in, it just so happens, April), the result of sunlight and water and fecund soil. I mean, leaves don’t even have to try. The “ghastly whiteness” of the blank page, on the other hand, requires the poet to manufacture from scratch not only branch and tree, but also the soil, the yard, and the poorly coiled hose sitting next to the garage.

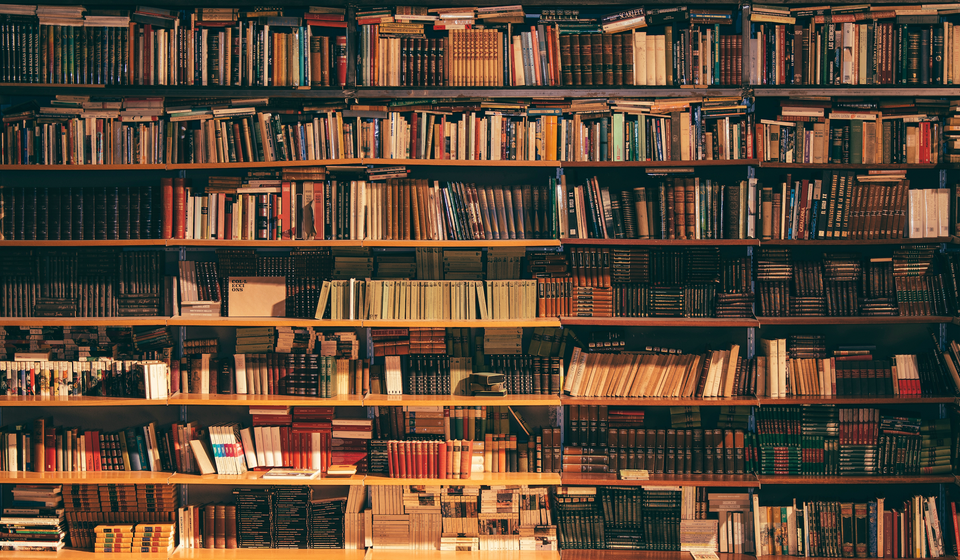

When we do manage to get some words down that sound natural and good, we have to then contend with readers. Keats, again: “[Poetry’s] touches of beauty should never be half-way, thereby making the reader breathless, instead of content.” The poems we write, if they’re really poetry, should leave readers “breathless”? It’s not often one can be truly enchanted with a single poem amid the crush of new work put into the world every single second. This past weekend was the meeting of the AWP (Association of Writing Professionals), an annual conference that attracts over 12,000 writers. Twelve. Thousand. I went one time, years ago. Walking into a room the size of a hangar I gazed at the innumerable stacks of poetry books and journals arrayed for sale on tables stretching in endless rows, like the rows of crates in the final shot of Raiders of the Lost Ark. I was breathless, all right. And a little sick.

It’s perhaps instructive that the two poets I’ve named so far are (white, male) “Romantics,” since that stripe of poetry has inflected, and infected, so much of what we’ve come to think of as poetic: that which is beautiful and passionate, the product of an individual, uncompromising genius. But Keats’s “axioms” are embedded in a letter about a comma; he begins by thanking his friend John Taylor for suggesting where to put one. There’s something charmingly earthbound in that fact, since it recognizes that the power of a poem comes in small arrangements of the material stuff that makes up the language—like this marvelous enjambment in “Ode to a Nightingale”: “The weariness, the fever, and the fret / Here…”—and it celebrates those friends who read closely enough, and care enough, to tell us to fix our punctuation.

If you want to be that friend, be that friend. Writing a poem a day means writing a lot of lousy poems; reading, actually reading, what your poet-friend writes each of those days means a mansion in heaven is being prepared for you. To engender the proper sobriety for approaching your friend’s, or anyone’s, poetry, consider Marianne Moore’s opinion on the subject:

I too, dislike it: there are things that are important beyond

all this fiddle.

Reading it, however, with a perfect contempt for it, one

discovers that there is in

it after all, a place for the genuine.

Buy the whole field. There’s a pearl in there somewhere.