Last summer, a feral cat gave birth under our deck. My kids and my husband were delighted, but I predicted future trouble: waste in the sandbox, an influx of coyotes. I proclaimed that there would be no feeding of the strays. My family nodded, and I think they tried to resist, but bits of bread kept finding their way onto the deck, along with Tupperware containers full of water.

I watched my family try to tame the kittens. I caved; I participated. I sat on the steps of the deck in the sun, silently watching, coaxing the kittens closer with a little food and a gentle gaze. I repeated this many times, and each time I was reminded of a book I read 24 years ago. Odd, isn’t it, how literary scenes sometimes follow you? What, I wondered, makes a passage stick? I started thinking about the brain, how it functions, what it chooses to remember. I decided the answer would make a good subject for a detailed, factual, scientific sort of article. I surveyed some friends, searching for a pattern to exploit. What I found was much better than that.

***

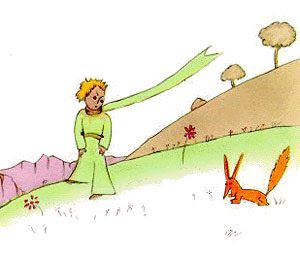

The scene begins simply, and is not well-defined by the landscape, the time, the architecture. It is a dialogue between Antoine de Saint- Exupéry’s title character, The Little Prince, and a fox.

The Little Prince, a young boy and ruler of a distant planet, has been on a grand tour of the galaxy, meeting all sorts of grown ups. Much of his experience perplexes him. He is now on earth, missing his beloved rose back home. He has discovered that roses grow in abundance on earth, and is disappointed. All this time, he thought his rose was special, but now he sees that there are thousands like her. It is at this moment in the story he meets the fox:

“Come and play with me,” proposed the little prince. “I am so unhappy.”

“I cannot play with you,” the fox said. “I am not tamed.”

“Ah! Please excuse me,” said the little prince.

But, after some thought, he added:

“What does that mean– ‘tame’?”

“You do not live here,” said the fox. “What is it that you are looking for?”

“I am looking for men,” said the little prince. “What does that mean– ‘tame’?”

“Men,” said the fox. “They have guns, and they hunt. It is very disturbing. They also raise chickens. These are their only interests. Are you looking for chickens?”

“No,” said the little prince. “I am looking for friends. What does that mean– ‘tame’?”

“It is an act too often neglected,” said the fox. “It means to establish ties.”

“‘To establish ties’?”

“Just that,” said the fox. “To me, you are still nothing more than a little boy who is just like a hundred thousand other little boys. And I have no need of you. And you, on your part, have no need of me. To you, I am nothing more than a fox like a hundred thousand other foxes. But if you tame me, then we shall need each other. To me, you will be unique in all the world. To you, I shall be unique in all the world…”

***

I ask my friends about memorable scenes in literature. Missy talks about Charlotte’s Web, how she struggles when they leave Charlotte at the fair to die. Jerry couldn’t make it through reading Where the Red Fern Grows out loud to his children. The moment when Little Ann goes to Dan’s grave and dies of a broken heart, he breaks down and his children are left wondering how to respond. Tom drinks coffee while he shaves, like a character in a Salinger novel.

Shawn recalls a scene from the Journey to the Center of the Earth. The setting is vivid to her, like a snapshot in her head. Chip reflects on the emotions that welled in him when Billy Parham shot the wolf in The Crossing. Matt recalls C.S. Lewis’s description of Aslan: Not safe, but good.

Laura and Jen can’t stop with one scene. Laura echoes Jerry’s attachment to Where the Red Fern Grows and adds Stone Fox, The Grapes of Wrath, Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Jen starts with A Tale of Two Cities, moves to Knowles: A Separate Peace, and then ponders the books on her shelves, looking for patterns.

I notice that five of the eleven scenes involve animals. Seven of the eleven titles are children’s or young adult books. I am momentarily excited, but then I realize that the phrasing of the question may have skewed the answer. My survey is flawed; I will have no objective data to savor, not even from this small sample. I give up on the article and go searching for something else to write about. After a few weeks, I fail. I reread The Little Prince.

***

The fox explains the benefit of being tamed:

“My life is very monotonous,” the fox said. “I hunt chickens; men hunt me. All the chickens are just alike, and all the men are just alike. And, in consequence, I am a little bored. But if you tame me, it will be as if the sun came to shine on my life. I shall know the sound of a step that will be different from all the others. Other steps send me hurrying back underneath the ground. Yours will call me, like music, out of my burrow. And then look: you see the grain-fields down yonder? I do not eat bread. Wheat is of no use to me. The wheat fields have nothing to say to me. And that is sad. But you have hair that is the colour of gold. Think how wonderful that will be when you have tamed me! The grain, which is also golden, will bring me back the thought of you. And I shall love to listen to the wind in the wheat…”

…

“One only understands the things that one tames,” said the fox. “Men have no more time to understand anything. They buy things all ready made at the shops. But there is no shop anywhere where one can buy friendship, and so men have no friends any more. If you want a friend, tame me…”

I think about my friends and what they’ve shared. I reread their comments, no longer as a statistical exercise, but as an invitation. Their perceptions shine; their lives sing; books are now woven into the ties between us.