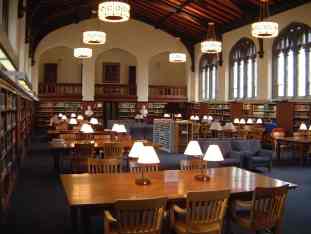

For the most part, I have a pretty good life as a grad student. Aside from time spent in class (and that crazy month right before seminar papers are due), I spend most days happily immersed in the writings of great scholars and statesmen of generations past, which means living a pleasantly hermit-like existence either in a magisterially peaceful, wood-paneled reading room at Union Theological Seminary, or sitting on my couch, curled up with a cat and a cup of coffee. But occasionally, I daydream about what else I could have done with my life — usually prompted by well-meaning jibes from relatives with MBAs who see no use for a PhD in English in the real world, or how I feel when I go online and my New York Times homepage brings news of turmoil in the social, political, and economic spheres, or even the shock I get at the contrast between my placid Morningside Heights neighborhood and some of the sketchier areas of town. On these occasions, the Ivory Tower feels like exile. I wonder guiltily about whether I buy my comfortable lifestyle at the expense of being uninvolved in the world around me, or whether I do so in order to avoid the responsibility of trying to improve it. Have I fled from the present world in order to escape into the past, and what account can I then give of myself to those who will inherit this world in the future?

In the past few months, I have found an unlikely model for thinking through these questions in Niccolo Machiavelli. I’m not sure how many other people in the world would admit that they want to follow Machiavelli’s lead in attempting to be socially engaged; now literally a by-word for bloodthirsty back-dealing and two-faced politics, we hear “Machiavellian” and think of classic stage Machiavels — Barabas, killing off a whole nunnery in Marlowe’s the Jew of Malta, or Shakespeare’s Richard III, putting the “murd’rous Machiavel” to school in his blood-soaked grab for the English throne — or its occasional use by psychologists to describe people with anti-social tendencies. Nevertheless, Machiavelli has proven a good guide for me not because of his unscrupulousness in the political present, but for his conscientiousness in approaching that present through the writers of the past.

While most people focus on the juicier catchphrases in The Prince that advocate ruthlessness and immoral political conniving, Machiavelli’s concern was not about morals as such at all. Rather, his lifework and writings were aimed at finding realistic ways of creating a stable, democratic political world. During the brief period in the early 1500’s when Florence operated as a republic, Machiavelli worked as a civil servant — in the second chancery and as a secretary to the intimidatingly named “Ten of War” committee — before the Medici family returned, took control of the government, and created a virtual oligarchy. Under the new regime, Machiavelli was confined to within 25 miles of the city limits, then imprisoned as a potential threat, and strappadoed six times (the legal limit was four and, bless him, he still refused to confess to anything) before being released. Unemployed and still under suspicion from the government, he exiled himself from the centers of political and social power in Florence and moved back to his family’s farm just outside the city, where he wrote all of his major political works. [1]

While there, Machiavelli wrote a letter to Francesco Vettori, the Florentine ambassador to Rome, asking for advice on how to use The Prince to regain entry into the political sphere, and it’s the tensions in this letter that haunt me as I wrestle with what it means to be involved simultaneously with the world of the political present and with the thinkers of the past. In order to take his mind off his present troubles, he says:

When evening comes, I go back home, and go to my study. On the threshold I take off my work clothes, covered in mud and filth, and put on the clothes an ambassador would wear. Decently dressed, I enter the ancient courts of rulers who have long since died. There I am warmly welcomed, and I feed on the only food I find nourishing, and was born to savor. I am not ashamed to talk to them, and to ask them to explain their actions. And they, out of kindness, answer me. Four hours go by without my feeling any anxiety. I forget every worry. I am no longer afraid of poverty, or frightened of death. I live entirely through them.

After so many years of anxiety and uncertainty, Machiavelli’s approach to the past seems to be about turning to a quiet, contemplative life where one forgets “every worry” of the present by living vicariously through those he studies. It’s a picture of comfort and solace to be sure, but where does the comfort come from, and how does one square these claims with his evident desire to be back in the thick of things?

The key for me to the meaning of his studies can be found in his adherence to humanism and its mode of civic engagement. Machiavelli, as any 10th-grade European history teacher will tell you, was one of the subscribers to the new humanistic learning that gained traction across Renaissance Europe, and that sought to revive the study of ancient and classical literature and history. The humanists believed that education in the classics formed effective citizens who would take part in the world around them, and who would use the wisdom of the ancients to refashion their political present. In this worldview, it is only by taking stock and contemplating the past that one can lead an active public life. Far from a turn away from the problems of the contemporary world, Machiavelli’s classical studies can only be understood as a whole-hearted embrace of the present and its problems.

In light of this, the comfort and the solace of studying the past comes, not from escapism, but from the capacity it gives us to deal wisely with our own time. Machiavelli likens studying the ancients to entering a foreign court, and casts himself as an ambassador, comparing policies and gaining knowledge and information to take back to his own realm. Studying the past gives us perspective on the present, allows us to see the scope and significance of contemporary sociopolitical events in light of the grand sweep of history, identify historical patterns and similarities by which we can predict outcomes and respond appropriately, and helps us acknowledge our own transience in the recognition that, just as early dilemmas were superceded by later problems, so also will ours be engulfed by those of the future. As Hannah Arendt, another great political philosopher, wrote earlier this century,

Life itself, limited by birth and death, is a boundary affair in that my worldly existence always forces me to take account of a past when I was not yet and a future when I shall be no more. Here the point is that whenever I transcend the limits of my own life span and begin to reflect on this past, judging it, and this future, forming projects of the will, thinking ceases to be a politically marginal activity. (Hannah Arendt, The Life of the Mind, pg. 413)

It certainly worked for Machiavelli. The immediacy of the republican crisis in Florence is now all but forgotten, but the judgments Machiavelli formed about it by studying the past have survived and continue to influence the way we think about politics in the European and American republican traditions, providing a means for us to conceptualize how politics work, now and in the future. And so with the image of Machiavelli before me, decently dressed and nourished by the ancients, I continue to study — not as a hermit, but an ambassador, reaching back to the past to get wisdom for the present.

[1] David Wootton, Machiavelli: Selected Political Writings, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1994.