We humans make sense of our lives by shaping them into narratives. Childhood is the exposition; romances, tragedies, and accomplishments soar up the slope of conflict to peak at the crisis of marriage, death, divorce, a degree, promotion, or publication. We organize little experiences like short stories: beginning, middle, end. Maybe this is why fiction is addictive: each new beach novel or young adult fantasy offers another compelling visualization of that neat arc. Maybe my life will make sense if it matches the triangulation of a fairy tale, novel, or epic.

I recently spent 3,200 miles on the road: 20 days traveling, 40 hours in a car. While there was no descent into the underworld, nor any large-scale battles, there was a cast of thousands, and I was a tiny voyager in unknown terrain. I re-imagine this pilgrimage as an approximation of an epic journey, especially since it was framed by encounters with life, death, love, and literature. Even a hobbit might accomplish such a jaunt and return home changed. Absurdly enough, J.R.R. Tolkien was so wound up in these events that his narrative colored my own, urging me to subcreate (or sub-subcreate?) my little story in light of his. And I’m not the only one to do that.

It began with a whirlwind trip to New Hampshire (7 hours from my Pennsylvania home) to visit my ailing grandmother. It continued with 18 hours to Chicago, carrying along the sweet sorrow of a final goodbye.

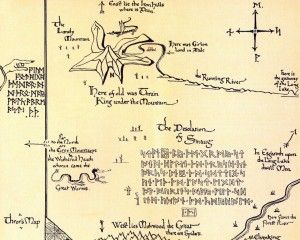

Then the literature begin pouring into the tale, as I spent three days studying the works of Charles Williams at the Wade Center. Surrounded by books by and about Barfield, Chesterton, Lewis, MacDonald, Sayers, Tolkien, and Williams, with maps of Narnia and Middle Earth hanging in the next room beside Lewis’s own wardrobe, it was impossible to avoid delusions of mythical grandeur.

After that, a few more hours on the road brought me to a place of villainous ugliness: Western Michigan University. But there, the collective contents of thousands of scholarly minds (22 pages of names) were spread in a glittering academic jewel-hoard known as the 46th International Congress on Medieval Studies. Panels and papers abounded on Anglo-Saxons, Aquinas, archaeology, Augustine, ballads, Bede, Beowulf, Bibles, Boethius, Byzantium, Castillians, castles, Chaucer, Cistercians, chroniclers, crusaders, Franciscans, Franks, freaks, gender & jouissance, Malory, manuscripts, marriage, martyrs, miracles, monasticism, mosaics, movies, plagues, poems, priests, prose, revisions, romances, sagas, songs, spirituality, stories, syllabi, symbols, teaching, texts, translations, Tuscany, video games, visions, voyages — and J.R.R. Tolkien. At any given moment throughout the four-day conference, there was a panel sponsored by the “Tolkien at Kalamazoo” society.

This is where the narrative-framing became, perhaps, a little bizarre. Tolkien scholars call Tolkien’s work “The Legendarium” (the exact provenance of this term is under dispute) and — this is the astonishing bit — scholars talk as if the texts of the Legendarium comprise the surviving documentary evidence of an actual, historical culture. Honestly. They write and speak with all seriousness about the stories as if they are chronicles of historical events; about the maps as if they plot a real topography; about the languages as if they have real grammatical rules, morphologies and etymologies — which, to be fair, they do.

You can see why I laughed at first. I mean, come on guys (and gals): it’s fiction! Of course, none of these scholars believe that they are studying the documents of an actual society. But I still thought: Get over it. Grow up. There’s real history to study, real languages that need translating, and you’re arguing about the etymology of Tinfang Warble?

Then I underwent an about-face. Instead of gently mocking these ardent scholars, I began admiring Tolkien for the profundity of his achievement. How magnificent that one man’s imagination could produce a made-up culture consistent, coherent, and comprehensive enough to stand up to such scrutiny! How beautiful that he could shape not only the products of his own imagination, but also the collective fantasies and fears of a generation, into a lasting narrative that continues to form and fulfill the literary longings of generations to come! “ . . . What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! . . . in apprehension how like a god! . . . ”

See, it’s a more official way of making our lives fit into stories. These scholars are part of a larger subculture of people who study literary fiction as if it has some kind of ontological reality. All literary scholars are doing that, simply by dedicating their lives to books. They structure their lives around books. They subject the language of fiction to close scrutiny, honing its meaning into clarity and relevance, or causing it to fall open and create a space for more discussion, more argument, and more meanings. They read poems in historical context as if the events surrounding the author’s life wrote the poem, then turn and read history as if it was written by the literature of its time. Historians go further and write history books as if they are narratives: this caused that, which caused that, which led to this crisis, which finally wrapped up in this resolution.

This obviously causes problems: Whose history? Who gets left out? Who decides what is crisis and which is resolution? Each historical narrative privileges somebody’s (or some ethnicity’s, or some nationality’s) story over someone else’s; one person’s tragedy is someone else’s victory. And this is true to some extent in individual lives: My acceptance letter may be someone else’s rejection slip. At the very least, I can’t know what the high point of my life was until I’m dead — and will we re-write our earthly tales in the afterlife?

Yet it’s necessary and healthy to plot episodes in our personal stories so they make some kind of bearable sense. After 12 days and 2,484 miles, I returned home, but the circle was not complete. Two days later, I got the dreaded call that my grandmother had died. Her 89-year-long story had ended, at least this side of the grave. What story she tells and is told now is beyond my ken. I drove a much more somber 7 hours up and 7 hours back, those hours framing the pain and muted pleasure of family reunited at her funeral. Her story was happy enough and long enough for most mortals, but nobody likes endings. We love sequels, and books in series. We weep as the closing credits roll, or turn the page to look for an epilogue. My grandmother’s epilogue — or whole new story — is written in a language I cannot read, for now. It may follow a narrative arc I have never imagined.

Like Samwise Gamgee, I return to home and garden, to continue to retell my adventures, tragedies, and victories according to shapes given me by fiction. The human story goes on, and my grandmother’s in mine, and mine in others’, and all of ours in the great narrative of history that will at last reveal its ultimate plot-arch only at the end of time. Meanwhile, we tell stories and sing songs to make sense of our lives, shaping little journeys into “there and back again.”