Playwright Neil LaBute has always been a master of malice. His plays, filled with the grand intricacies of name-calling and the subtlety of allusive pricks to the heart, are studies on the subterraneous cruelty we have grown accustomed to brandishing against those we say we love.

In his newest play, reasons to be pretty, now playing under the direction of Terry Kinney at the Lyceum Theatre on Broadway, LaBute’s characters have moved beyond the point of grinning and bearing anything. These characters are fed up with being treated unjustly. They have unleashed some primal forms of cruelty that are familiar in appearance, but when placed under the careful microscope of Neil LaBute, can be as brutal as a National Geographic documentary.

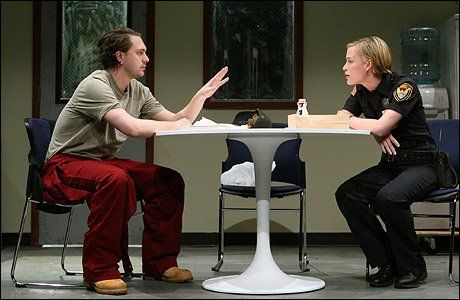

reasons to be pretty opens with the play’s main character, Greg (Thomas Sadoski), being verbally ripped to pieces by his girlfriend, Steph (Marin Ireland), for a comment he made to a co-worker that was meant to be “harmless” and completely unheard by anyone – especially his girlfriend. Greg’s comment concerned Steph’s physical appearance, which compared a certain body part to the new ogle-inducing blonde that works upstairs. The body part: Steph’s face. The abominably nasty word used to describe Steph’s face: regular.

The deadly comment sets off a series of events that place Greg in the judgment seat, where he is charged with the seemingly impossible task of being an adult. That is to say that he is fessing up, trying to be responsible, and asking those around him to listen, forgive, and change. If you’re a character in a LaBute play, this task is like juicing a two-by-four.

Steph breaks up with Greg and her immense anger turns into utter resentment in an achingly awkward scene where Steph stands up in the middle of the local mall’s food court and reads aloud Greg’s physical flaws. With vengeful flashes of Medea, Steph spouts off Greg’s physical defects executioner-style, remarking on everything from his premature balding to his (clear throat) nether-regions. But in the play’s first glimpse of compassion, Steph reveals why her predatory litany does not fit Greg’s crime: it wasn’t true. What Steph read aloud to the world was fabricated, constructed to be hurtful. What Greg said to his buddy about her face was honest. Steph reveals her longing to do good, which is constantly trumped by her lust to punch back.

While Greg attempts to repair his shattered relationship with Steph, his co-worker and best friend, Kent (Steven Pasquale), fans the flames of Greg’s moral predicaments as LaBute’s archetypal – yet always enthralling – testosterone-driven male. Like an old high school friend you didn’t want to run into over Thanksgiving, Kent’s locker room-language induces laughter at first and audible moans of bitterness later. Kent’s wife, Carly (Piper Perabo), is the play’s picture of “acceptable” physical beauty until she becomes pregnant and undesirable to Kent.

What unfolds is a whirlwind of conflict where people are asked to be accountable for their cruelty, or at least explain it. LaBute’s script has been revised since its off-Broadway run six months ago, and focuses less on an obsession with looks than on the ramifications for such conceited fascinations, which is what sets the play apart from his earlier works.

With plays like The Shape of Things and Fat Pig, LaBute has become the theatre’s expert on our culture’s physical obsession. Fat Pig is the story of a thirty-something male who falls in love with an obese woman. In the end, selfishness wins out, as the man dumps the woman and admits that even “true” love will fall victim to his obsession with appearance. This heartbreaking, deep-seated truth – no matter the cost, people are out more for themselves than others – is at the root of LaBute’s plays.

But reasons to be pretty adds another element to the cruel-on-cruel crimes of his characters: by the end, most of them are desperately trying to be responsible. Whether they succeed at growing up is debatable, but it is a theme that LaBute has only scratched the surface of until now.

In the playwright’s note, LaBute writes, “I’ve written about a lot of men who are really little boys at heart, but Greg, the protagonist in this play, just might be one of the few adults I’ve ever tackled.” Along with this new sense of adulthood, the characters in reasons find themselves with a moral dilemma. If they are to grow up and act responsibly, then they insist those around them do so as well. In the theatre, this is the point when characters get hurt or do some hurting themselves. In reasons, this ethical catharsis culminates in a rough and bloody fight, Greg being the character who prevails. Was this violent match the point of Greg’s becoming an adult? The audience sure thought so, applauding and whooping for the average Joe who finally took justice into his own hands, as if to say, “Yes, the adult thing to do is to beat the shit out of those who wrong you.” We the audience, apparently, were as unequipped to bang the gavel as the fallen characters we were observing.

In essence, LaBute’s characters in reasons are struggling from taking on the role of judge and possessing the mercy to rule outside their own self-interests. They are trying to adopt a morality that ultimately falls apart when those they love and care about fall short of such a high standard. This is LaBute’s equation for cruelty, and sets him above the mold in being able to express the normalcy of the chaos we live in.

All of this makes for a dizzyingly exciting night of theatre, with countless thematic implications that go deeper than just the skin. Even though many of LaBute’s scenes are filled with comically heavy arguments, it is the more subtle yet equally as potent jabs that tell us who these people really are. Their attempts at true goodness and beauty are executed with a sort of awkward frailty, like a child taking the training wheels off.

As always, LaBute’s dialogue is rhythmically beautiful, profane, and clever. He has concocted some of his most hilariously well-crafted insults and slurs to date, making one feel a little less pretty and somehow disturbingly more at home for laughing with and at the characters.

The performances are outstanding, particularly Marin Ireland’s acerbically biting yet exposed Steph, and Steven Pasquale’s wretchedly funny Kent. Thomas Sadoski as Greg provides us with a perfectly magnetic performance of LaBute’s everyman.

Director Terry Kinney (co-founder of Chicago’s continuously impressive Steppenwolf Theatre), brings an energy and flow to the play that makes it as comical as it is tragic, allowing us to hear LaBute’s dialogue at such a clipped and naturalistic pace that you would feel as if you were eavesdropping if you weren’t in a massive Broadway theatre. Rob Milburn and Michael Bodeen’s sound design, and Kinney’s scene transitions, accelerated by a spinning siren and loud rock music, give the feel of an unpredictable joyride (it’s hard to go wrong when you toss a Radiohead number into the action).

David Gallo’s sets and David Weiner’s lighting provide a working class warehouse where the drama unfolds. Amidst the set’s towering shelves of stacked products of plastic, one wonders if this warehouse is the image of Greg’s world around him – a place with walls of baggage too high to scale, the work of unloading it never to be completed, like some American middle-class Sisyphus.

LaBute’s characters all hide behind their own egos through books, looks, and machismo, and by the end of the play are not necessarily stripped of their own selfishness, just a bit more responsible for it. This breeds a blatant compassion in his characters and, as one who has kept a keen eye on LaBute’s work, is an intriguing trail to see the prolific playwright go down. LaBute is raising some fascinating questions in reasons to be pretty. What do we value in relationships? Is it looks? Honesty? Flattery? Sacrifice?

And most importantly, in all seriousness: what would it take for you to love an ugly person?

By Neil LaBute; directed by Terry Kinney; sets by David Gallo; costumes by Sarah J. Holden; lighting by David Weiner; sound and music by Rob Milburn and Michael Bodeen; technical supervision by Hudson Theatrical Associates; production stage manager, Christine Lemme; fight director, Manny Siverio; general manager, Daniel Kuney. An MCC Theater production, presented by Jeffrey Richards, Jerry Frankel, MCC Theater, Gary Goddard Entertainment, Ted Snowdon, Doug Nevin/Erica Lynn Schwartz, Ronald Frankel/Bat-Barry Productions, Kathleen Seidel, Kelpie Arts L.L.C., Jam Theatricals and Rachel Helson/Heather Provost.

At the Lyceum Theater, 149 West 45th Street, Manhattan; (212) 239-6200. Running time: 2 hours 15 minutes.

WITH: Thomas Sadoski (Greg), Marin Ireland (Steph), Piper Perabo (Carly) and Steven Pasquale (Kent).