“I know that suicide is one of the deadly sins. But being unhappy is a great sin, too… ”

In Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry, unhappiness is a constant companion. Mr. Badii is a man suffering, and he makes a decision to silence his heartache through suicide, which he declares is a solution for pain granted to man by God himself. Whether this choice was made compulsively or slowly, violently or with calm conviction, by the time we meet him, Mr. Badii seems resolute. He has determined the manner (sleeping pills) and the place (the side of a hill overlooking Tehran). He’s even dug his grave already. The only obstacle that remains is finding someone who will bury him after his death.

Our unexpected knight errant rides through the streets and outskirts of the city, searching not for glory or honor, but for a hand in his final rest. As he passes by laborers old and young, his gaze is searching and slow, patient for the right person to assist him. Eventually, he meets a young soldier and, while driving out to his makeshift grave, attempts to enlist his help. The nameless soldier is tacitly shy, but his reticence morphs from discomfort into fear into abject refusal as he comes to realize Badii’s request. The soldier can’t begin to imagine aiding someone in suicide. In his incomprehension, he flees.

A short while later, Badii comes across a seminarian studying in Tehran who is somewhat more receptive to Badii’s plight. The two have a long, insightful discussion about the nature of life, the inescapability of suffering, the mercy of God, and our right—or lack thereof—to choose when we die. However fruitful the conversation is, neither side is swayed, and the student declines to help.

After many hours of searching, Badii finally finds someone who agrees, albeit reluctantly, to bury his soon-to-be-dead body. Mr. Bagheri, a taxidermist at a nearby museum, clearly sees Badii’s pain and determination. He accepts Badii’s terms, although he also exhorts Badii to reconsider. Bagheri’s argument is not based on lofty, abstract ideas about the value of human life. Instead, Bagheri calls upon the sensual and the imminent. He waxes nostalgically about the sharp taste of mulberries, summons the tender reds and yellows of sunset, and recalls the bracing splash of water from a spring.

After his encounters with these potential gravediggers, Mr. Badii moves forward with his purpose. But it is finally here, in Mr. Bagheri’s words, that we find the essence, the being, of Kiarostami’s film. Taste of Cherry never sets out to establish a grand ideological treatise, but instead forms itself into a play of the senses centered on the pain of another. It dwells in the wilderness of experience, a landscape of personhood at once recognizable, yet ultimately strange and unknowable.

*

We never learn out of what suffering or longing or loneliness Mr. Badii has come to his embrace of death. If we demand to know why, we will be frustrated. But if we allow ourselves the space of not knowing, we begin to sense him—the dance of conviction and pain in his glances; the reminiscences of exuberant, younger days; the search for human connection, even now in his twilight.

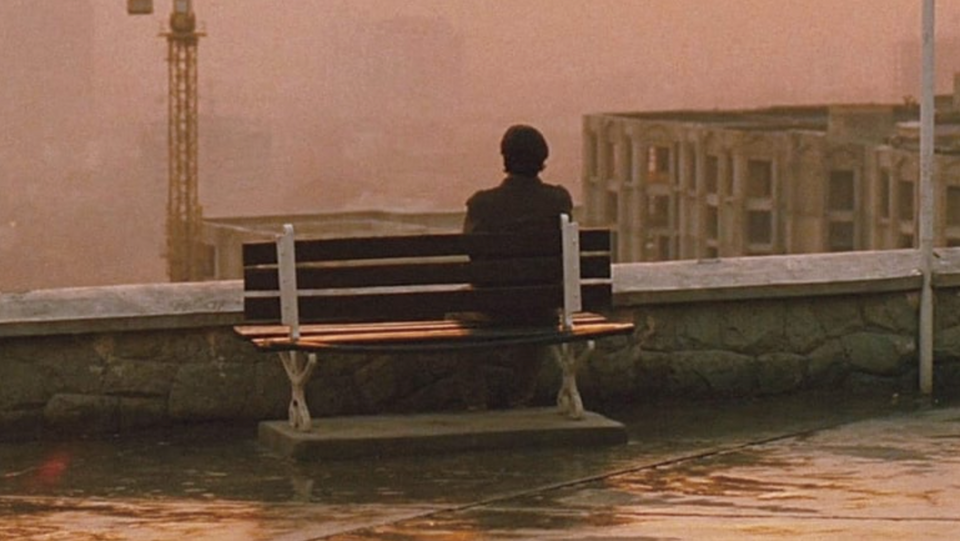

Kiarostami does not bring us close enough to Mr. Badii to feel his open wounds as our own, but he brings us close enough to glimpse them. Kiarostami chooses to materialize the phenomena of Badii’s torment through imagery. The film’s palette bathes the landscape in umber and vermillion, evoking barrenness. As his search for a gravedigger proves fruitless and the day ebbs away, the golden hour seems to evoke a diminishing of both his hopes and his life, which are ironically in competition with each other. After stopping at a construction site, Badii watches dirt pour into a quarry and transfixes on his shadow being consumed within the cascade. As vehicles pass by, he is gradually obscured until he disappears entirely, baptized in dust to nothingness. In a strange inversion of Coleridge’s mariner, Mr. Badii finds earth, earth everywhere, nor any yet to bury him.

The movie keeps us slightly removed from Badii, despite our being immersed in the imagery of his desire. Denied full understanding, Kiarostami gives us encounter. We must view the conversations with his passengers within the same framework of desire—they are all speaking out of and toward their individual motivations—and approach them all with the same humility and reserve. If the audience finds the passengers’ arguments for why Badii should not kill himself unpersuasive, that’s fine. Kiarostami includes them to serve as the very thing Mr. Bagheri talks of: glimpses of a life. We detect in the soldier the nervousness of youth and the displacement of being far from home, and a response conditioned by rigidity. Likewise, it is easy to sense the seminarian’s profound concern for deep matters, though his intellectual focus distances him from Badii’s plight. And as Mr. Bagheri tries to convince Badii to change his mind, he tells a story of his own attempted suicide. For him, the simple taste of some mulberries brought him from the brink of death. He then lists off so many experiences of sweetness, asking Badii if he is truly prepared to forego them.

As the very title implies, this is a movie about sensing, not about knowing. The encounters are just that—tastes, gestures of impermanence that perhaps reach out toward something transcendent.

*

Just as we never receive the revelation of Badii’s heartache, so too we are blocked from knowing his fate. The horizon of his life is a plane we are not able to cross. In a particularly disruptive move, the movie ends with a behind-the-scenes coda depicting fragments of the shoot. With this decision, Kiarostami denies us the happy ending we yearn for; he also elides the interpretive ending that would have rolled credits at the fadeout. Instead of showing a change of heart or a fade to black, Kiarostami pulls back the curtain and shows us the set and the crew. He forces us to confront the question of what we wanted from the film.

Those are the questions of life and death: what makes the former worth it, what right do we have to the latter, what becomes of us when both are behind us? Kiarostami never seeks to directly answer these questions; instead, he implies that his movie simply can’t resolve them. We are given a gesture in place of revelation.

We look to movies for reflection and for imagination: to learn about ourselves, to learn about others. To reconsider our world, to discover new ones. The reflective power of movies can endlessly search us, but our imagination can exceed our experience only so far. How can the experience of death be conveyed by a director, or felt by an audience, when neither have tasted it? When it comes to the teleological endpoint, movies are resigned to gestures. Never finality.

By cutting the imaginative end short, Kiarostami turns us back to reflection. Taste of Cherry is honest about its own inability to truly put us in the life of another, about the chasm between us. It knows it can’t be an answer, but even as a gesture, it offers something sweet.