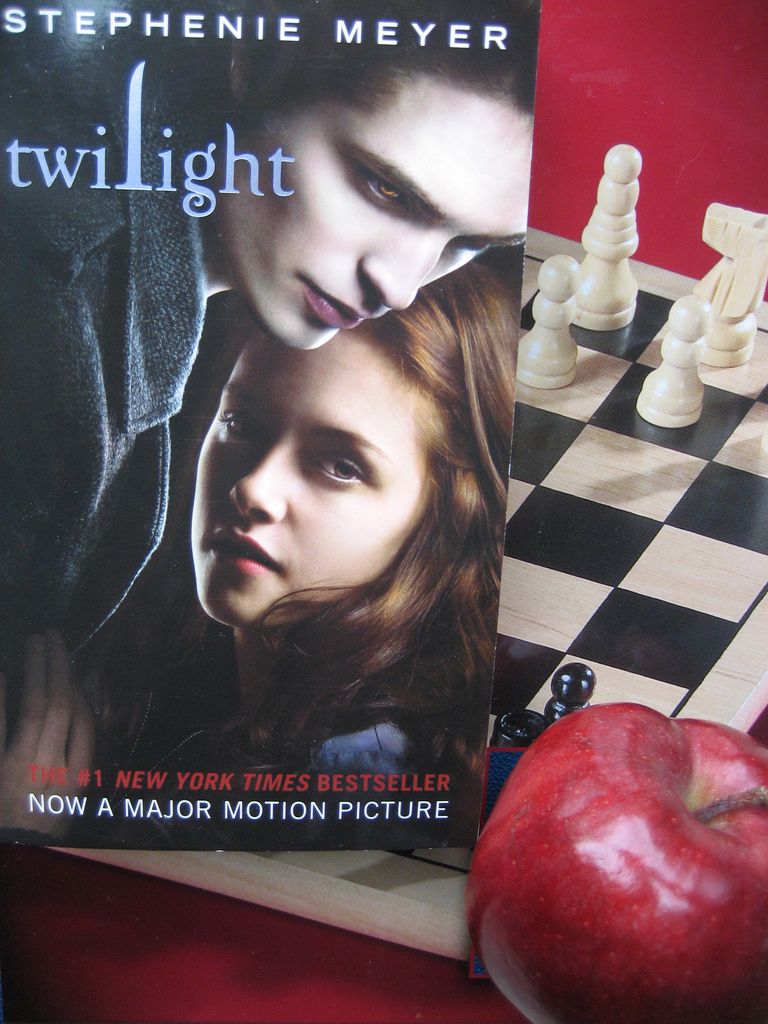

Before they became all the rage amongst sixth-graders, I wanted to write a story about vampires. I rode a wave of inspiration for about fifteen minutes before abandoning my project to the towering junk pile of books I never finished writing.

A few short years later, Stephanie Meyer would lead a parade of the tragically postmodern faux-undead in what is perhaps the most disappointing resurrection of an otherwise timeless monster. Now people ask me if I regret not finishing, that maybe I could have had some stake in the recent vampirical pay day. My answer is always no, which is typically met with accusations of jealousy. Don’t I wish I’d written a story like Twilight, they ask.

Now if a person has to ask me that question, they obviously don’t know me very well, because the answer is unequivocally no. But the Kool-Aid being served on the Twilight bandwagon is potent, and so I don’t take offense at such sentiments, misguided as they may be. In fact, I’ll even do you the favor of offering up my justifications for, up until now, ignoring everything that has ever spilled forth from the Twilight series.

First and foremost, Stephanie Meyer didn’t actually write a story about vampires. Instead, her version of the undead takes the fearsome mythological demons and turns them into emasculated prairie dogs, simultaneously delivering them up on an implied sexual platter to the freshly-excited hormones of the prepubescent and the perverted longings of the hopelessly romantic.

That’s not to say that there’s anything wrong with fictional creatures evolving – I take very little issue with the Twilight vampires being able to wander around in the sun – but disregarding the root truth of vampires, which is that they are demonic and evil, and depicting any of the lot of them as capable of love for humans is irresponsible, and at the very least, ludicrous. As such, Meyer not only successfully bastardized the nature of vampires, but worse, she also encouraged (though I’d imagine unwittingly) a shamefully false sense of truth about that which is wholly good and that which is wholly evil.

Fantastical stories of romance have always been big sellers. From the Bible to Shakespeare to Danielle Steele, the tales that makes women swoon and men snicker (while swooning secretly so you’ll think we’re big and tough like the guys in those stories) continue to rank as The Most Read Stuff On The Planet. Trashy romance does exceptionally well; in fact, it makes up for the bulk of fiction novels sold. And granted, the rippling biceps described by the likes of Nora Roberts rarely, in reality, belong to men with a romantic sense of equal potency, but we tend to accept that on the premise that it is still within the potential of a man’s nature to behave as they do in those novels.

Meyer’s world, on the other hand, immediately breaks down in the consideration of nature because it is, by no means, natural for a vampire to fall in love with a human. And before the naysayers have a chance to play devil’s advocate here, let’s remember that one of the most defining characteristics of the undead is that they eat people. A vampire falling in love with a beautiful woman would be tantamount to me falling in love with a well-bred cow, and while you can argue that such a thing is disturbingly still within the realm of possibility, you should also admit that you wouldn’t want anything to do with me if that’s how it went down.

Such is not the case with dear Edward, whose warm tenderness manages to capture the hearts of women both fictional and otherwise as he insists that eating people makes him feel like a monster, although he seems to have accepted drinking animal blood as harmless enough.

And therein lies the rub: conflicted or not, Edward is a monster, not a man, and the consequence of Meyer’s fiction is that we are no longer able to see that through the trees. Not only that, but with his charming good looks and fairy-tale sensitivity, Meyer has made the monster into one of the Good Guys.

This is problematic because – whether we realize it or not – what we see, hear, read, and otherwise assimilate affects the way we see the world around us. For adults, perhaps this is permissible; we all need a little reality break from time to time. But Meyer’s base audience is not adults, but young adults who remain as easily-influenced as children while simultaneously being slammed by the same desires as their elders amidst the first inklings of developing a world view and morality – a dangerous recipe when it comes to stories as seductive as Twilight. In quiet suburbia, where no one understands poor Bella in a new and unfamiliar world, she finds solace in the mysterious bad boy with the intoxicating eyes, a wild smile, and an unclear sense of rebelliousness. After a flirtatious dance in a circle of mounting sexual tension, the bad boy sweeps the innocent girl from her feet and shows her what life (or is it death in this case?) is all about.

Still, the story of the good girl and the bad boy is as old as any story involving human nature, and I’ll even concede that vampire stories are often, if not always, sexualized in some way or another. Indeed, sexuality is part of the seductive nature of vampires, and arguably what makes them so dangerous in the first place (if you believe in mythological creatures, that is).

The problem with Edward and Bella – and most other surfacing stories of the undead – is that the seductiveness of the vampire is glorified, not condemned. Even in Bram Stoker’s original masterpiece, Mina feels nothing but wretchedness after being taken by Dracula; she dedicates herself to his destruction after the fact. Bella, on the other hand, takes a taste of damnation and decides to roll it around on her tongue for the rest of eternity. (An unfortunate irony, no doubt driven by the success of such stories, is that one of Bram’s descendents recently tarnished the revered name Stoker by publishing a sequel to Dracula which consists mostly of bloody lesbian sex, glorified alcoholism and morphine addiction, and, like Twilight, the choice to turn to the darkness for the sake of love.)

What’s worse is that both the Dracula sequel and Twilight are only extreme examples of a phenomenon happening to the modern vampire – indeed, even the modern monster – the world over. In our consumerist culture of sex and excess, fear has taken a backseat to desire. Monsters suddenly have feelings. Where feelings remain neglected, gore, sexuality, and general debauchery act as the springboards for tainted stories of torture and abuse, while other tales of misplaced redemption impair our ability to recognize evil for what it really is.

Whether rooted in mismanaged eroticism or flat out perversion, we have over-humanized creatures which, despite their appearances, have very little else in common with mankind. If the creatures themselves were the ones redeemed, then there might not be much to complain about; almost every decent work of literature relies on symbolism to convey a message.

But when the symbolism suggests that we humans can somehow safely cross to the dark side through a heart of erotic love, thereby finding some sense of eternal happiness, we jade ourselves and misguide our youths, thus further perpetuating the merciless consumerism which drives the majority of people and cultures. There’s nothing wrong with Eros and there’s nothing wrong with redemption. But the conveyance and use of such themes, like any other, bears a sense of responsibility which stories like Twilight disregard, while the people who read them continue to empower authors to propagate gross sublimation within the consumerism of a deprived race – namely, mankind.

Ultimately, this is the challenge and the curse for all artists: to commit to a responsible delivery and depiction of the stories and symbolism we use to better understand our world. A created world entirely devoid of evil wouldn’t do much good in helping us to better comprehend our own reality, but neither does a world where the evil is glorified – not only as desirable, but also as the thing which ends up being chosen. We will always have a choice between good and evil, but the idea that evil might ever be permissible as the right choice is both a tragically naïve idealism and a detriment to society as a whole.

If I ever do write my vampire story, I think I’ll make Bella and Edward part of its beginning. Five hundred years after Twilight, when the vampire couple is spending a romantic evening on a country hillside with a eclectic assortment of barnyard animals, innards spilled out on a picnic blanket in the worst distortion of prix fixe since Manhattan’s West Village, they’ll be seduced by Qumran, the vampire evangelist who convinces them that people are, after all, the finest of cuisines. Emotional and psychological chaos ensures, driving the Twilight twins to embark on a raging killing spree, numbing whatever human sympathy is left in them.

Then vampire-hunter extraordinaire, Abraham Van Helsing, ninety-seven years old but hell-bent on ridding the world of demons, will swoop down from the time machine he was secretly building with Jack Seward after the death of Count Dracula, single-handedly drop-kicking the heads off of all the world’s remaining undead, starting with Bella and Edward. Having put stakes in their hearts and garlic in their mouths, Van Helsing retires back to nineteenth-century England where, faced with the decision to properly publish his successful sojourn through time and his second victory over the damned, he decides instead to settle down in the isolation of a quaint villa in Messina, quietly passing from this life to the next without a single mention of the undead lovers he so valiantly slew. After all, some things are better left in the dusty, crooked confines of our imaginations.