To put my literary cards on the table: I am a rabid acolyte for David Foster Wallace (hereafter DFW), his personality, and work. Cult leaders dream of disciples with my dedication and single-mindedness. Wounded by the failed cultural terrorism of older avant-garde fiction, I found DFW. Or more precisely I received him about a decade after his mid-90s fame—stumbled upon stories bursting with irony, meta-irony, grad-school immaturity, damaged people, and deep faith. But fear not; I’m no evangelist, and this is not a spittle-flecked sermon of the Good News of the Church of DFW.[1] From him I received tiny but dense truths: that we are lonely, that this world makes us feel lonely, that we don’t want to feel lonely. The continual reading and re-reading of Infinite Jest became a spiritual practice, a literary S&M, or perhaps my personal form of faux-monastic self-flagellation. In him I found myself, or at least what I like to think of myself. He wrote how I wish I thought, with a smart and funny Heisenbergian brain. Infinite Jest was his fractal Summa on anxiety and addiction, where the jest is infinite because our desires are bottomless.

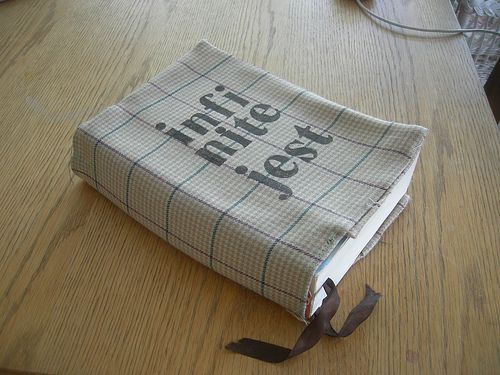

Amidst charting the mini-monstrosities of the protean collective consciousness, Infinite Jest is about worship. To be human is to worship. Every heart bows before something: a feeling, an activity, a calling, a vision of itself. And Americans are good at super-sized worship. Rome’s got nothing on our bacchanalia; we put the excess in excess. And to a certain point we are proud of it, relishing our materialism, flaunting it. America stands as both the architect and victim of affluence and endless entertainment. It doesn’t require a DFW-sized intelligence to see that Hell is cool, flat, crowded, and so is Wal-Mart: both sell happiness. Simply put, as a nation of addicts we are a nation of worshipers; and most of the time we worship ourselves. As DFW said in an 1996 interview:

“[D]rug addiction is really a form of religion, albeit a bent one. An addict gives himself away to his substance utterly. He believes in it and trusts it, and his love for it is more important than his place in the community, his job, his friends.”

Here is the blurry cultural edge, where excess becomes addiction, where what you consume begins to consume you. The opened door locks behind you. Desires don’t fight fair, their gravity warps you, coiling you around yourself. Interventions, groups with “Anonymous” in the title, self-hatred, confusion, fraudulence, love of suffering, paralysis, bright nights and dark days appear like animate pre-prom pimples. In these dark times, addiction’s friends—boredom, loneliness, fragmentation—are the cultural forces from which DFW’s fiction draws its own physics, computing the large arcs and subtle distortions of American life. Infinite Jest provides a diagnosis of this communal dark while pointing to the fires of humanity amidst the cold. He portrays how humanity lives, rejoices, and even loves amidst the addiction, the movements of entertaining materialism. If Infinite Jest gives the diagnosis, the 2006 Kenyon Commencement speech opens a window into his prescription; a distillation of what worshipping well might look like. He says:

“Worship your intellect, being seen as smart, you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out. But the insidious thing about these forms of worship is not that they’re evil or sinful, it’s that they’re unconscious. They are default settings.

And the so-called real world will not discourage you from operating on your default settings, because the so-called real world of men and money and power hums merrily along in a pool of fear and anger and frustration and craving and worship of self. Our own present culture has harnessed these forces in ways that have yielded extraordinary wealth and comfort and personal freedom. The freedom all to be lords of our tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the center of all creation…The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.”

What we worship gives our heart objectives, our imagination form, and our mind geography. How we worship—the habits, liturgies, and set of activities—form the way we live and move and are in this world, how we inhabit time. The Kenyon address advocates a type of being, an everyday mindfulness, a spirituality of attention—as though he saw the true form of life in Simone Weil’s maxim, “attention is the highest form of prayer” and ultimately, true love. In The Pale King, DFW’s unfinished novel, the character Chris Fogel says that with “simple attention, awareness…stay[ing] awake off speed” everyday humanity “blaze[s] in an almost sacred way.” In his fiction, DFW made the leap of faith into redemptive relationality—creating stories that ask you to sacrifice your attachment to yourself, to fall into the fullness of other-centered empathy. Tragically, what this careful awareness entailed escaped him, for in 2008 he committed suicide. DFW, self-described as a “black hole with teeth,” was eluded by the physics of mental peace. His advice at Kenyon, it would appear, did not determine his course of action, but rather reflected what he observed, what he longed for. Can we trust the addict, the one who committed suicide, a person who wandered into the wilderness and never returned? Can the lost guide? DFW was certainly no saint, but lives of truth take many forms.

Consider Parisian curate Abbé Marie-Joseph Huvelin, an avowed spiritual director from the 19th century. Throughout much of his life he ministered amidst chronic sickness, able to provide nourishing guidance and a spiritual home for many. Years later, his private journals revealed he experienced severe depression and persistent thoughts of suicide. An 11-page segment of his notebook contains his name written over and over with “He does not exist” and “I used to be” scratched across it. Out of this complexity Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams invokes the category of the “holy neurotic,” arguing that Huvelin reveals the freedom of love to work through a life marked by cavernous guilt and self-hatred. DFW’s fiction is analogous to Huvelin’s spiritual directorship. Amidst the howling self-conscious tornado of prose, bloated details with no plots, characters that are sacks of naked self-knowledge without selves, and the footnotes (Oh Dear God the footnotes), I was evangelized, invited into an act of faith. That which pained me also ended up sustaining me. The faith DFW advocates focus on a state of being, rather than faith in the one who gives humanity being. Humanity doesn’t necessarily have a God-shaped hole in its heart, but a worship-sized one. DFW educates us in the form and rhythm of faith, reminding us of its cost. This form of worship, of living, is summarized by Madeleine L’Engle:

“We live under the illusion that if we can acquire complete control, we can understand God, or we can write the Great American novel. But the only way we can brush against the hem of the Lord, or hope to be part of the creative process, is to have the courage, the faith, to abandon control. For the opposite of sin is faith, and never virtue, and we live in a world which believes that self-control can make us virtuous. But that’s not how it works.”

The search for mental and emotional health in the modern world may ring Pelagian, but this is not altogether inappropriate. DFW’s writing can save us from the everyday idolatry of the default setting, the cultural autopilot of excess and addiction precisely because his fiction is a gym for the moral imagination. He shows that the daily commitment of faith is hard (or should be) when your eyes are breathing in the miasma of the 3000th daily advertisement. Because whether you recognize it or not, you are being invited to worship. Hell, you (and I) are worshiping. Regardless, humanity can’t control or consume its way out of this omnipresent idolatry into health and holiness. An act of the will, the sheer force of self-control, is not the key to making head and heart habitable. The calculus of control or even choice is exactly what addiction and worship do not provide. I believe that, in the light of Christ’s work, worship is where God promises to save us from ourselves, the event in which we find ourselves uncoiled from our addiction to self-worship. This is not a trite cliché, but a common truth—an irreducible inevitability of what it means to be human, to be a creature. Good worship—worship that seeps into your cells and atoms—is just as much a form of rest as it is a form of activity. DFW was a man who rarely found rest, and never found Sabbath. This is the physics of worship. Sabbath is the “womb with a view” where awareness is remade and life’s choreography redone. The Sabbath, the communal time where we are unmixed from our daily addictions. The physics of faithful worship—embodied liturgies of motion and rest—resist the atomistic and addictive energies of the culture, integrating us with what some theologians call “the grain of the universe.” Good physics of worship are not something one accomplishes, but something one receives as a gift. Some of the greatest gifts are to be re-given again and again and again—every Sunday, in fact.

A more religious man than he is given credit (his favorite book was The Screwtape Letters), DFW loved Brian Moore’s Catholics, the story of an abbot incapable of prayer. Any prayer was pure fraudulence for him; mass was not a miracle, but a pious ritual. Yet the story ends with the “faithless” abbot kneeling with his broken community, and praying the Lord’s Prayer. Here, beyond the point of choosing to believe, beyond the point of control the faithless pray, the anxious rest, and the lonely are known.

[1] This is not entirely true.