“Art can be weird.”

—Ron English in Hi-Fructose

Imagine a little trip back to college, freshman year, Philosophy 101: that earth-shattering, mind-blowing class. Ten weeks into the semester, readings in Metaphysics, Epistemology, and Ethics have already trashed old assumptions and made The Matrix look more plausible than it ever did before. Now the professor writes on the board:

AESTHETICS = THE STUDY OF ART AND BEAUTY

The class sighs in relief. Finally, something soothing. Images of naked goddesses float before the collective imagination while ghostly strains of Mozart echo in the mind’s ear.

But what’s this? Four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence — that calls itself music? Music can’t be silent! And what’s that? A urinal in an art museum? A urinal isn’t art! And after tape-loops of train whistles, the creepy tones of Sprechstimme, Hugo Ball carried on stage in a tinfoil mitre, and a couple Dadaist poems, Plato’s cave sounds as home-sweet-home as Kansas. Aesthetics is not so simple after all. Apparently, it can be as difficult to define “Art” as to define “Reality.” And beauty might be in the eye of the beholder or beauty might be an irrelevant approach after all.

There are two overlapping movements currently underway — worldwide art phenomena of great energy and influence — that redefine Art yet again and smash barriers implicit in the oppositions “high” vs. “low,” the gallery vs. the street, art vs. protest, and the classic vs. the cutting-edge. They do their best to defy taxonomy, so even calling them “two movements” is questionable, as is the attempt to label them. But for this conversation’s sake, these contemporary visual phenomenon can be discussed under two modes: “Street Art” and “Pop Surrealism.” While they began in different venues, they do have some similar effects and are, perhaps, growing closer all the time.

Street Art, also called urban art or post-graffiti, is not so much about What is Art as Where is Art? It was originally art executed outdoors in a public space, usually in a metropolis. In the last seven years, it has caught fire across the globe, flaming through city streets, rail lines, subway tunnels, and high-rise buildings. It has burned its way through Amsterdam, Bristol, Cork, Lille, Lisbon, London, Los Angeles, Madrid, Melbourne, Milan, Montreal, New York, Paris, Rome, São Paulo, Sydney, and Tokyo, becoming fantastically prolific, popular, profitable, and even — in some cases — respectable. To the uninitiated eye, most Street Art just looks like graffiti. It is often spray-painted, stenciled, or stuck on posters. Some contain a ubiquitous, ambiguous “tag”: the artist’s logo or visual pseudonym, such as an arrow for Above, a stick-figure with a big head for André, the face of a giant for Obey. However, the artists explain that the major difference between their work and graffiti is its public nature: “Unlike graffiti, where the work is intended to make sense to a peer group, street art is open to everyone to understand.” [1]

Understanding is very important to Street Art, because it exists to communicate a specific message. This is often political — protesting the Iraq war or the installation of surveillance cameras, for instance — or ideological — many works of Street Art combat commercialism. CutUp Collective made a practice of slicing up billboard images and rearranging the squares into new scenes that question the advertising industry. Many satirize politicians or celebrities: In one attributed to Dolk, the Pope wears a dress, striking Marilyn Monroe’s famous subway air-vent pose. One brave artist, Banksy, painted protest images all along the West Bank wall as soldiers fired at him.

And that’s another facet of Street Art that once defined it but is beginning to shift; originally, it was illegal. Spray-painting on the surfaces of public buildings is, after all, vandalism. One artist calls it “a beautiful crime.” [2] Many artists got arrested. For some, the thrill of working at night in a forbidden space under extremely dangerous conditions involving heights, electrical wires, scaffolding, moving vehicles, or live bullets was as essential as the act of making art. Over time, some artists realized that prison would put a quick stop to their careers, and began finding legal ways to display their work. Some now paint only with permission of building owners. Others make it removable, on posters, stickers, or other paper installations. And others have moved on to canvas and have begun hanging paintings in galleries. As a matter of fact, alternative galleries have sprung up just to showcase art from the streets — thereby taking it out of the open public space altogether.

Pop Surrealism, also called lowbrow, underground art, art brut, or urban contemporary, is not so much about What is Art, either; it’s more about How is Art? It is another outsider, with origins in cartooning and comic book illustration, but has its galleries, too. Like Street Art, a piece of Pop Surrealism might be a sculpture, an installation, even a toy or other artifact; but it is usually painting. Or, more accurately, within this larger movement there are fine art painters in the Pop Surrealist style.

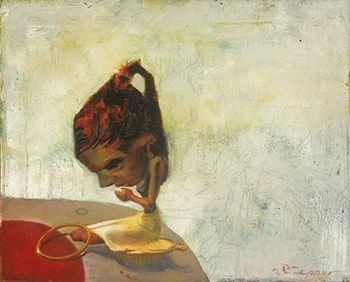

I recently had the privilege of interviewing a young painter, P. Tepper, who loosely identifies himself with this movement. He described the methodology used by some of its most influential artists: Todd Schorr, Mark Ryden, Joe Sorren, and Greg Simkins. To this list might be added Robert Williams and many more.

Tepper explained that a Pop Surrealist painter will first choose one of the great European masters such as Monet, Rembrandt, or da Vinci. Next, he will pick his subject matter from pop culture, often something strange, bizarre, juvenile, kitschy, or carnivalesque. Then he will paint this contemporary subject using the techniques of his chosen master. This in itself is an odd juxtaposition: A baby doll or a toy painted with Baroque glazing, Impressionistic impasto, or a pointillist approach. But that’s not all. He will also skew, mar, maim, and distort the image into a creepy, nightmarish caricature. The technique is masterful and the content is bizarre. There are a lot of monsters, creeping creatures, disconnected body parts, corpses, ooze and slime, zombies, foxy ladies bordering on soft porn, worms coming out of eyeballs, children butchering or being butchered. It’s an ugly world beautifully painted.

Because of the excellent technique, many of these works hang in the world’s major art magazines and galleries, including MOMA, the Tate Modern, and even the Louvre. But then again, so does Street Art. There are other ways these two movements are moving closer. Both are interested in “smashing the façade of artistic standards.” [3] Both are fast-growing, multi-international trends with large followings and significant commercial success. But while Street Art is coming indoors, into galleries and private collections, Pop Surrealism sometimes goes outdoors. Ron English, with whose quote this article began, took a group of artists to Texas and asked cattle ranchers, “Hey, can we paint your cows?” They didn’t mean paint pictures of cows. They meant, paint pictures on cows. So they did. They painted some with zebra stripes, some with rainbow stripes, and some with maps of the world on their flanks.

I knew art could be weird. But I hadn’t known it could be quite this weird. Looking at Street Art or Pop Surrealism, I think: “Why, oh why, didn’t I take the blue pill?”

[1]Eleanor Mathieson and Xavier A. Tápies, Street Artists: The Complete Guide, p. 7.

[2] André, quoted in Street Artists p. 8.

[3] Hi-Fructose: New Contemporary Art, vol. 16.