Not recognizing himself

He wanted only himself. He had chosen

From all the faces he had ever seen

Only his own. He was himself

The torturer who now began his torture.

—Ted Hughes, Tales from Ovid

Eight or nine months ago I was still in the honeymoon phase of first-time smartphone ownership. Instagram was the first app I embraced. Armed with a battery of hazy filters, I set about making the street corners, stairways, and appliances of my daily life into art. My following crept past the single digits (not including parents), and I became aware of the lusty satisfaction of having a photo “liked.” It was not a new concept: shared experience, the promise of a digital community that transcends geography by replacing it with a cheerful topography of glitzy, artistically emphasized experiences.

My moral sense was skating through this landscape undisturbed until one day, checking the photo stream, I noticed something that prickled my neck hair. A friend of mine was adding pictures from his actual honeymoon. The photos were tasteful and appropriate; they depicted a modest fantasy of splashing water, umbrellaed cocktails, and endearing hugs by sunset. But suddenly the smartphone in my hand felt less like a link to my peers and more like a keyhole to a peepshow. My honeymoon with the media stream was over. There was something categorically wrong about projecting, for the general public, a life event that is intimate by definition. Far from forming a sense of community between my friend, his new wife, and myself, it created, unaccountably at first, the distance one feels when still deciding whether or not to buy a product. I had seen these flashy pictures before—in cologne advertisements.

A few weeks later, a freshman in my college writing course turned in a paper that, using statistics and marketing documentation from major companies like Starbucks, demonstrated convincingly that Facebook is, essentially, a self-marketing tool. The website—probably without knowing it—has simply substituted “profile” for “advertisement,” and, while its participants are not actually selling themselves (this caveat excludes band, company, author, and political Facebook pages), they are making the same editorial decisions with their own image as an advertiser does with a product: Only the positives are displayed.

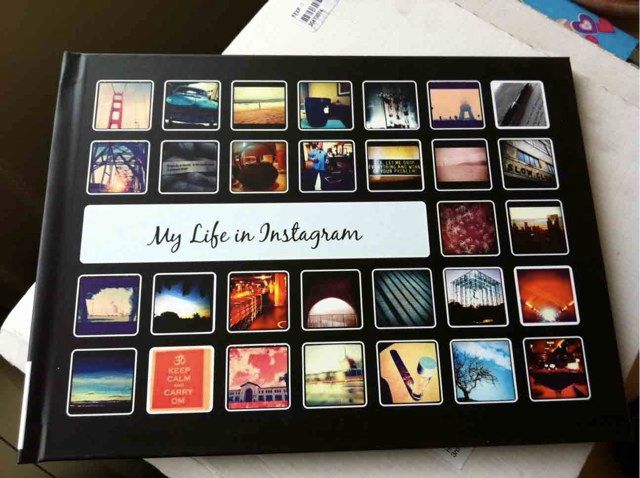

As an educator I do not tell Facebook when I am a little overboard with the whisky on a Thursday night, or fighting with my wife, or having some embarrassing trouble digesting a spicy taco. No: Facebook is only informed of my most sanitary thoughts and actions. Because my online reputation can make the difference for me between dollar signs and unemployment (I have known teachers who have lost their jobs as a direct result of posting “red cup” photos, in spite of the fact that the cups were holding only grape juice), I treat my identity, insofar as it exists on the internet, as a product—one that I must advertise. Instagram boils this process down to its most subversive state by being dedicated exclusively to that most powerful advertising tool of all: Image. In the end, our photos may be about sharing experience, but only experience that reflects positively on our marketable image. Even our photos of church group, or a friend’s birthday, or exercise at the YMCA are, if we admit it, about us. Every photo is a “selfie.”

This reality commands an army of unintended consequences. Anyone who works in advertising knows that to keep a company perpetually sellable is a career-long process, which requires a full eight hours of slogging labor every day, and leaves the copywriter or image consultant tired in her chair at home. But to advertise one’s self perpetually by means of social media is a wearisome project. It requires a portion of mental attention to be available at all times, looking for the compartmentalize-able moment.

Anyone who has used Instagram with any regularity, or known someone who does, has felt this peculiar brand of exhaustion. “Hold up!” your friend shouts while you walk back from the wharf at sunset, and you turn, to notice her ten paces behind, selecting a filter. At dinner, the waiter is pulled away from a crowded six-top that just sat down under the opposite window to snap a group photo of your whole table—after all, these get-togethers happen less and less. Your mother, of course, is taking a picture of her food. Where are these photos going? Do they matter to those involved in your current experience? Not at all. They only matter to those who have missed it, and can do nothing but make them detached from whatever it is they happen to be doing, as they, just for half a second, check the photo stream.

The topography of shared experience has only one geographical feature and one explorer: The Self. This is a cruel twist of logic, but it isn’t a new one. In the months that I first started to abandon social media, I happened to be teaching Ted Hughes’ translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and the myth of Narcissus came to hand as the perfect barometer of a civilization that has always been just as self-concerned, but has only recently developed the tools to socially interact with its own face.

Narcissus became rooted in the end, and similarly, the new narcissism of social media has the effect of rooted-to-the-spot mental stagnation. To record life at the same moment we experience it requires more attention then we can spare. We will give our devotion to one process or the other. But there is a deeper problem: To self-advertise is to make perpetual war on the fallibility of our own nature. It forces us to conceal the flaws that real friends and loved ones must experience and forgive in order to genuinely love us. In the end, the photostream isn’t a new landscape but a hall of mirrors—one that is easy to get lost in.