A gift from my musically esoteric boyfriend, my record player has been my proverbial time capsule to the American Southlands I call home. I load dusty albums from the past–kings and queens of country–on the record’s arm and they drop by themselves. So I stack up five of those melancholy discs, and listen to the A-sides. They play through, drop down, and I flip and start with the B-sides. Sadness, coated with betrayal, layered with loss, all held within the grooves of the black vinyl. These artists sing a different tune than the post-millennial country. They sing about dusty clay roads, but they also sing about the lowest lows of desolation and the prayers of the darkest night. They sing about prison and adultery, tragedy and comfort. Their words are not contrived and sometimes not even catchy–slow and dull and long–dragging on one continuous chord. But they come from a place exclusive to the South, a place that the South could be forgetting.

I was raised in and by the hills of Virginia so I am acquainted with bluegrass and the bucolic banjo pluck of the Appalachians. Life in the South to me has meant mountains and magnolias, bourbon and a sauntering pace of life. But until recently, I did not know the darkness of the deep musical movements coming from the South less than a half century ago. In this place, in the acapellas of low sadness and the hymns of wandering, I have found camaraderie with the land that hemmed and honed me as a young woman and as a contributor to family and place. The deeper I listen to Emmylou Harris, Loretta Lynn and Conway Twitty, Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash and the like, the deeper I enter the old South; a place where despondency, pride, and revelry exist within each other. Ever since the needle scratched and crackled through that first disc, the open space between me and my homeland, and all her past sins, triumphs, and profundity, has sealed.

Emmylou Harris was quoted recently in Garden & Gun magazine saying that she has given up on present-day country radio. “It no longer has that washed-in-the-blood element,” she said. And she’s right, alluding to this spiritually infused land where God is seen more with dirty shoes holding out redemption, rather than a glowing halo bestowing blessings. Some present-day artists–Gillian Welch, Patty Griffin, David Rawlings in particular–hold fast to the tenets of powerful, bleeding and vulnerable music of the South, but these artists are rare. The influence of the South is too often watered down to an occasional mechanized twang, girls who wear dresses with cowboy boots, and cheap beer cans. And behind the barbeque and pickup trucks, we have lost, or are at least losing, our edge.

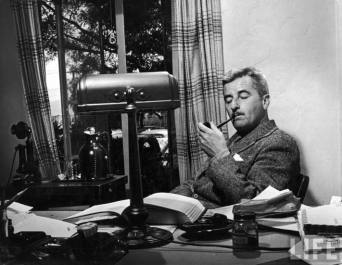

It’s the same edge that the writers of our Southern fiction have made famous. The place of darkness which honed the literary voices of Flannery O’Connor’s grotesque, Edgar Allan Poe’s nightmares, and William Faulkner’s pontifications on death. The South provided a backdrop unmatched by other geographies, fostering art that feeds on our ability to make the worst of our lot.

This land of moonshine and muskets belies a deep disenchantment. O’Connor wrote that since we lost the war in the 19th century, we have ‘had our fall’–the type of fall that keeps the whole populace awake to their potent inability to pride themselves on themselves. We are aware that we can believe deeply and still, with sweat and blood, lose everything. The artists who embody the South do not wash worries in whimsy, but attempt connection amidst isolation, loss, and disillusionment.

Flannery O’Connor herself said that we may not be Christ-centered as much as we are ‘Christ-haunted.’ And these ghosts, as much as they keep us fearful and frightened, keep us wide-eyed and questioning. We have been the “Bible Belt” for decades, a symbol of centrality as much as corporal punishment. And we Southerners have been beaten by our own faith. We are holy tormented and wholly sanctified.

The South has created from this fallen place and offered the nation a voice otherwise unheard. A perspective cast through an interminable mix of searing nostalgia, bated hope, and a weighty present balanced between the two. For decades, artists let this land mold their perspectives. It was the Southern zeitgeist, and it is this curious mix of hope and sadness.

More recently, the blurring of state and cultural lines has come as a detriment to artists. We lose our senses and loosen our allegiances, as we drift above the lands. As O’Connor said, when we cease to create from the reality of our place, this Southern place, we have lost ourselves, and we have lost the South. Makoto Fujimura has said before, we have a language for the waywardness. What the South is beginning to miss is the language for the ties that bind. So the challenge for Southern artists now is to stay connected–to keep the ankles in the mud and the fires smoldering. To be a product of the palpable senses, and to let the sights, sounds, emotion and memory of your place build your reality and your platform. We need to reorient our perspective to move beyond what we do in the South, beyond fishing, hunting, and cooking with butter, and enter into who we are, in joy and in trial.

And perhaps, optimistically, we can find ourselves anew in the people who understand and channel this spirit, regardless of their geographical upbringing. Because in the end, what the South did was connect in the darkness. It is the invaluable voice of a fallen community that still echoes from my record player, and is still found within my pages of “A Good Man is Hard to Find.”

Johnny Cash sang that he wore black for the sick and lonely, for the reckless, and the mournin’, for the poor and beatin’, and the prisoner and the victim. And as artists create today, perhaps it is our duty to take on the strands and fringes of black both to honor and connect us to the spirit, land and people of our place. So we take from the fragmented pieces of our community’s collective conscience, take the black, and take the blood, and in doing so, create an enduring piece of work, reminiscent of this old melancholy.