“Around the throne of God, where all the angels read perfectly, there are no critics—there is no need for them.” –Randall Jarrell

American culture tends to harbor little love for the critic. For them, every day is the Day of Judgment. They are vampiric leeches on the life of art. The critic’s role, at best, is to help direct money and time toward more desirable places—a cog in the industry of culture, a modest contributor to sales figures.

So what is criticism? Simply put, criticism is the practice of reflecting on art in public. Most of my “criticism” happens between the end credits of a movie and the theater’s front doors. Just because the movie is over does not mean you are finished. Standing outside the bathroom, waiting with others for others, a shared pile of enjoyments, dislikes, and interpretations quickly accumulate. The experience leads to shared words.

If you Rip van Winkled your way from the 1960s to now, a lot would be the same. As a community and a practice, criticism is obsessed with the terms of its conversation, resulting in a continual re-visitation of its societal purpose. In its short history, crisis is routine for criticism. Where does it belong? The academy? Popular magazines? Your blog? Cave scrawlings of genius hermits? Who is it for? The rich? The amassing poor? The bore? Who does it better? A.O. Scott or Terry Eagleton? Men who eat chocolate or women who skydive? Each answer is part of an unending obsession with the partially secure definition.

Often, discussions of criticism act as an extended answer to the question: are things getting better or worse? The meditations on the status of and responsibilities of criticism pull from the critic’s emotional state—whether apocalyptic, favorable, or Eeyore-esque—with general declarations providing the theoretical foundation. Like generational-based thinking, narratives of decline or ascent are simple ways to mistake your own emotional outlook for the prevailing narrative itself.

But what are words of criticism for? What is their purpose?

Criticism often starts as a form of narrative truth telling. While specifically talking about fiction in her essay Fine Writing, Cranks, and the New Morality: Prose Styles, Annie Dillard says fine writing is:

not a mirror, not a window, not a document, not a surgical tool. It is an artifact and an achievement; it is at once an exploratory craft and the planet it attains; it is a testimony to the possibility of beauty and penetration of written language.

To borrow from this helpful metaphorical winnowing: if fine writing is the exploratory craft, then fine criticism is the bright atmospheric reentry, the conversation afterward where you share your findings with those back on Earth. Most criticism is like a travel memoir, reportage on the far country, the return after the encounter, the interpretive event after the reading, watching, or listening—“When someone goes on a trip, he has something to talk about.”[1] It is narrating and reflecting on the form and course of your specific subjective encounter.

However, the question remains: what is the purpose of the narrative truths of this travel memoir?

Truth, like Guinness, often does not travel well—there are better and worse ways of transport. Problematically, I have a disposition towards the universal, a predilection toward authoritarian uses of “the.” Truth is especially dangerous in the hands of Christians (like myself), for when Christians start talking about truth, it is often because they want the conversation to end. The will to truth is often the will to power. But the truth is not the end.[2] Truth telling is where criticism starts but it is not where criticism, specifically good criticism, ends. Ending a conversation with an assertion of “truth” is the equivalent of buying lumber at Home Depot, and thinking you’ve built a house. The question always becomes what one does with truth.

A helpful way for figuring out the value of something is by figuring out its costs when done poorly. What is the cost of bad criticism? At what expense is bad criticism—hideously wrong engagements with art—written and published and read? Bad criticism threatens to make those who ingest it worse readers, viewers, and listeners of art. The modestly immodest intention of criticism’s narrative truths is to make you a better reader, viewer, listener. As poet and critic Randall Jarrell states, “What is a critic, anyway? So far as I can see, he is an extremely good reader—one who has learned to show to others what he saw in what he read.”

While the seduction of the pulpit is strong, critics aren’t primarily there to get you to agree with them (though sometimes, even often, that seems to be the animating hope) but to enact, to model a well-done reflective act. In “The Function of Criticism,” T.S. Eliot quotes Clutton Brock: ”The law of art…is all case law.” Other experiences with art become a model, and provide a form of wisdom for our own artistic engagements. The faint pedagogy of criticism is in its work as testimony.[3] It is a travel memoir that teaches us how to travel.

Walter Benjamin writes on this relationship between truth, narrative, and wisdom:

All this points to the nature of every real story. It contains, openly or covertly, something useful. The usefulness may, in one case, consist in a moral; in another, in some practical advice; in a third, in a proverb or maxim. In ever case the storyteller is a man who has counsel for his readers. But if today ‘having counsel’ is beginning to have an old-fashioned right, this is because the communicability of experience is decreasing. In consequence we have no counsel for ourselves or for others. After all, counsel is less an answer to a question than a proposal concerning the continuation of a story which is just unfolding. To seek this counsel one would first have to be able to tell the story (Quite apart from the fact that a man is receptive to counsel only to the extent that he allows his situation to speak.) Counsel woven into the fabric of real life is wisdom. The art of storytelling is reaching its end because the epic side of truth, wisdom, is dying out. This, however, is a process that had been going on for a long time.

The truth of criticism is about having counsel. Typically counsel is in the content. X leads to y. Character is destiny. Eat your vegetables. With criticism, counsel is in its form. Think about watching this way, listening this way, enjoying it this way. Someone else’s experience contains wisdom for your experience. There is an analogy of experience, we can learn from the artistic encounters of others. This is criticism is at its most useful, when its bossiness is a little more indirect.

Lurking in the background of this idea of criticism as a testimony, a travel memoir full of narrative truth, is the idea that consumption of good art isn’t good enough. Simply watching movies doesn’t necessarily train you to watch movies better (nor does watching good movies make you a good person). It tends to just train you to watch more movies. In the land of life, liberty, and entertainment, the ideal human is the ideal consumer, one who consumes and disposes with nothing in between—life as a bed-bound Netflix binge—your soul nothing but the pattern of your purchases. This version of the human reduces us to organs of appetite, a mouth attached to an ass—consumption and disposal become indistinguishable acts. What is absent is digestion, time in between. In the act of encountering art, criticism is the time between.

But currently, “Speed is God, and time is the devil.” Ultimately this version of the human and artistic consumption reveals our diseased relationship with time, what Sven Birkerts calls “time sickness.” Happiness and speed become synonyms. We dream of forms of agency and action that are not available to us. To riff on Mr. Churchill, we shape our time and then our time shapes us.

“I have never found anywhere, in the domain of art, that you don’t have to walk to. (There is quite an array of jets, buses, and hacks which you can ride to Success; but that is a different destination.)” –Robin Scott Wilson

Encounters with criticism entail a small alteration in the relationship between time and engaging a work of art. To frame it through the Christian calendar, criticism can be the Advent of the art world. Engaging criticism requires that you look back, that you remember, assimilate, digest, and wait. The simple fact of reflecting adds time to my encounter (and is a small act of faith, and a demand, that the art means). This time is about refining the activity of attention through the activity of reflection. We might see through a glass darkly, but some glasses are darker than others.

Near the end of college, I became obsessed with John Updike. It started with Roger’s Version, and quickly gained momentum. Luckily, every used bookstore has at least one shelf segment of Updike books, so my newfound addiction was inexpensive. My reading of the seventh Harry Potter novel was put off for months due to The Centaur, Poorhouse Fair, In the Beauty of the Lilies, Pigeon Feathers, The Bech books, and a vast sea of criticism, etc.

Damn, that man could write a sentence. If Shakespeare was English at its most agile, then Updike was English alive with simple delights—a particular blend of enchantment and attentiveness to the anatomy of the American routine. I loved the moments when his writing was like a camera stuck in a close up. There is no forest, no trees, nothing but this single leaf and Updike’s encyclopedic words of prose and praise. There was something approximately scriptural about it.

Then came the criticism. I read Sven Birkets’ article, “Running Out of Gas,”

“The self, however grandiose, is finite; the wells do dry up.”[4]

I read Wallace’s “John Updike, Champion Literary Phallocrat, Drops One; Is This Finally the End for Magnificent Narcissists?”

“Mr. Updike’s big preoccupations have always been with death and sex (not necessarily in that order), and the fact that the mood of his books has gotten more wintery in recent years is understandable-Mr. Updike has always written largely about himself, and since the surprisingly moving Rabbit at Rest he’s been exploring, more and more overtly, the apocalyptic prospect of his own death.”

Then, I read Nicolas Baker’s U and I.

“He teaches even in his transgressions.”

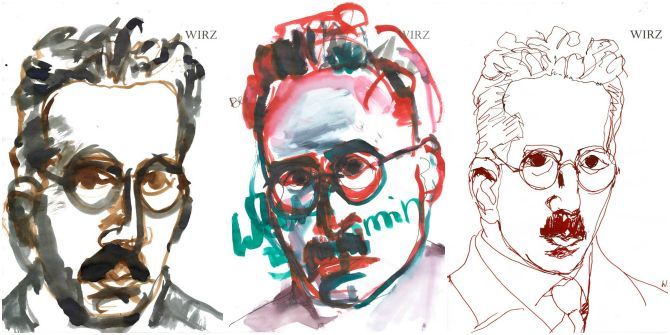

After each engagement with this winding road of criticism, patterns became apparent—the use and abuse of female bodies stood out. His “reflexive contempt” as gatekeeper for the realm of literary fiction led to frequent uncharitable critical missteps. My ear picked up the Updike auto-tune. How all of his characters spoke with a homogenous polished tone. Updike was the singular ousia manifest in infinite hypostases.

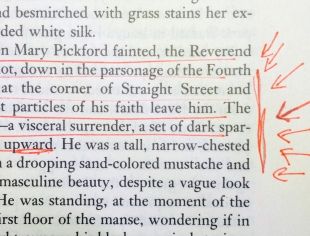

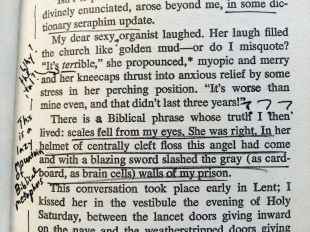

Finally, I read Month of Sundays, Updike’s novel about a philandering minister. And if I compare these marginalia to my initial Updikean encounter, the underlines are less frequent; the question marks are larger, bolder—with some sticking out of the text like a line of Loch Ness monsters. This marginalia differs remarkably from my notes in In the Beauty of the Lilies, with its flurry of arrows that are afraid to touch the hallowed text itself. My criticisms had congealed; my loves were sculpted down to their dense cores.

Criticism can provide a possible structure (a posture of approach) to and for the artistic experience. This is the common project, the shared mission of this space. As philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty states, “the discovery itself calls forth further quests.” Criticism is wisdom for the “further quests.” With each return, our means of travel, the nature of our experience, are shared, refined, critiqued. Criticism is there to help train your senses, the artistic hungers, and your reflective capacities.

If life is a problem, then art is not a very effective solution. If art is a question, criticism is not its answer. Don’t read criticism looking for answers; be on the hunt for forms of engagement.

CITATIONS:

[1] Walter Benjamin quoting a German saying.

[2] However, if I am to be honest with myself here, and if one were to press me on it, any discussion of the truth would involve me invoking Christ, because Christ is not a footnote, until he is.

[3] This understanding of testimony is heavily indebted to Alan Jacobs’ Looking Before and After: Testimony and the Christian Life.

[4] On an odd note of recent literary criticism history, this essay was published the same day, in a different magazine, as Wallace’s strikingly similar article.