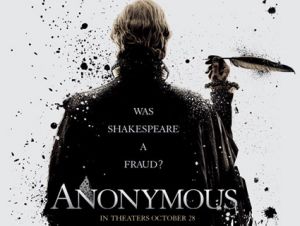

Well, the reviews are already out there. I didn’t read them before writing this, but perhaps you did. If so, The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Guardian, The LA Times, Rotten Tomatoes, and whoever else you read about films have already told you that Roland Emmerich‘s Anonymous is little more than a showcase for pretty boys to strut about in gorgeous, historically inauthentic costumes, speaking anachronistic lines and participating in fictional events. There is a good deal of beautiful skin bared, along with some not-so-lovely skin (please, keep your tights on). It is good for a few laughs: the buffoon Will Shakespeare (played by Rafe Spall) has his well-timed (if neither original nor accurate) Oscar acceptance moment, and Mark Rylance as Henry Condell spices up the chorus of Henry V with a little horsey impression. Indeed, I laughed through most of the movie, but for mostly the wrong reasons: I was incredulous, amused, and bemused by its clichés, its psychological implausibility, and its lavish big-budget spectacular emptiness. I laughed, too, as a critic and scholar, at the clumsy cuts and flashbacks (is that golden boy the Earl of Essex now, or the Earl of Oxford then? Is that one Queen Elizabeth’s lover, or son, or . . . ew), at the few nods to research (the alternative titles of Twelfth Night, or, As You Like It — really, that’s about as deep as it gets, so don’t worry if you haven’t quite finished that PhD in Early Modern Studies), and especially at the [not-so-] surprise Oedipal ending.

You see, this movie didn’t make up its mind. It could have been an educational immersion in 16th-century England that plunged its audience into the sights, sounds, and society of Elizabeth’s and James’s reigns. Or it could have been a watertight case for the Earl of Oxford’s authorship, ravishing the minds of its viewers with compelling evidence that he was the man who wrote “Shakespeare.” Or it could have been just a good movie.

But in it, Christopher Marlowe (Trystan Gravelle) dies at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and in the wrong way. The Earl of Essex (Sam Reid) commissions a performance of Richard III (it was Richard II). A Midsummer Night’s Dream is performed before Queen Elizabeth I (played by mother-and-daughter Vanessa Redgrave and Joely Richardson) and court in the 1550s with de Vere as proclaimed author, then performed again in the 1590s as “anonymous”: the Queen remembers it perfectly, while everyone else forgets it entirely. Doublethink? Or blooper? Henry V is de Vere’s first play presented under Shakespeare’s name at the Globe, to huge crowds and wild acclaim. Its manuscript is found, at the end of the movie, among the secret plays Ben Johnson (Sebastian Armesto) is supposed to publish after the Earl’s death. Subtlety, or stupidity? The Earl of Oxford (played by Rhys Ifans and Jamie Campbell Bower) delivers a speech about the material power of literature-as-propaganda that would not have been possible unless he had read Marx. A piece of Mozart is played at his wedding. Ben Johnson, Queen Elizabeth, and Shakespeare himself share a nineteenth-century, Romantic psychology about authorship, artistry, and individuality. The thing is a mess.

And while that Will Shakespeare, in the pastiche world of the film, could not conceivably have written those plays, and that Earl of Oxford probably could, there is no attempt to present a scholarly case for de Vere’s historical authorship. Dozens of books abound, scholarly, popular, objective, and partisan alike, that lay out a persuasive case either against Will of Stratford as author, or for de Vere Earl of Oxford as author. I’m a staunch Stratfordian, and I could probably lay out a better case for Oxford’s authorship than that film did.

I think I will. Here goes.

So, there’s this kid named Will Shakespeare, who is from a working-class family, may have gone to the local school, didn’t go to college, labored as a low-class actor (disreputable trade, that) in London, invested in real estate, dealt in grain and brewing, retired early, and was obviously more interested in money than literature. His wife and daughters were illiterate. He didn’t leave anybody any books or papers in his will. His name is spelt two different ways on the three pages of his will, and it’s known that illiterate people sometimes had their lawyers or other representatives sign their names for them. How could such a person, with no connections at court, little knowledge of classical training, no travels abroad, and a decidedly avaricious turn of mind be the author of the immortal and sublime canon?

On the other hand, there is Edward de Vere. As a nobleman, he would have received the best education of his day. He was raised by the Cecil family: both Cecils, father and son (Robert is played by Edward Hogg, William by David Thewlis) served in turn on Elizabeth’s privy council, essentially running the empire as unofficial equivalents to today’s Prime Minister. De Vere spent a good deal of time at court, traveled to Italy, saw the Commedia dell’arte, spoke several languages, stabbed a man through a tapestry, had three daughters (think Lear’s), lost his beloved first wife Anne (think the love-comedies or the bereaved Macbeth’s sorrowful speech), was known as a successful playwright (of comedies), blah, blah, blah. Oh, he died 12 years too early, but somebody else slowly produced and published his plays posthumously.

The movie touches on some of these themes, mostly visually without comment or discussion, and makes its persuasive case more on painting Shakespeare in a poor light than on investigating documents and conditions. But is that really the point? I don’t think so.

James Shapiro’s recent, brilliant book Contested Will takes a different approach to the authorship question, and one I would like to appropriate here. Although the sections of his book are entitled “Shakespeare,” “Bacon,” “Oxford,” and “Shakespeare,” respectively, he is less interested in presenting and critiquing the case for each man’s authorship than in psychoanalyzing the people who believe so-and-so or so-and-so wrote the plays.

Instead of asking, “Did the Earl of Oxford write the plays?” Shapiro asks why Freud, Mark Twain, Helen Keller, and others believed that the Earl of Oxford wrote the plays — and why did they believe this then, and there? What were the material, social, and psychological conditions that led them to accept an arguably ridiculous theory?

That is what I want to ask. Why this movie, why this message, here and now?

For the message is a strange one in this world. The message of Anonymous is essentially that a normal guy, an average middle-class fellow, could not achieve greatness. Why this message, now, when the “little guy” (or girl) is occupying the public square, storming the financial district, toppling dictators, and instituting democracy? If the little fellow, or the young person with an ordinary education, can overthrow a government, why can’t he write a few dozen popular plays?

Shapiro, in the end, lays out a very persuasive case for William of Stratford’s authorship, primarily based on the playwright’s intimate knowledge with the acting company (the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, later the King’s Men), the theatres (the Theatre, the Rose, the Globe . . . ), and the material conditions of acting in Elizabethan and Jacobean England, especially the new conditions that arose when Shakespeare’s acting company moved to the indoor Blackfriar’s Theatre after Edward de Vere’s death. I am convinced by his scholarly, readable case. I am not convinced by the conspiracy-theory attitude of Anonymous, in which everybody from the Queen herself through her privy council down to Ben Johnson, Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Dekker, and Thomas Nashe know the royal secrets. The film makes it appear that anybody at all who was paying attention could have figured out that Will didn’t write the plays, Edward did, yet that the thinking and unwashed masses alike have been mysteriously duped ever since. It doesn’t hang together. I suppose it appeals to the kind of mind that wants to believe NASA never put a man on the moon, JFK was killed by the U.S. Government, 9-11 was an inside job, and the like.

Sure, there were personal and practical considerations in making this movie, such as Roland Emmerich’s private interest in the story and the need to wait until Shakespeare in Love fervor died down so patrons would flock to the box office for another movie “like that.” Well, it isn’t like that. And since Anonymous was pulled from national release and only available in limited theatres, I couldn’t even bring my eager literature students, fresh off of Hamlet, to see it. Instead, I slogged through the slush-puppy misery of an October snowstorm to see it in lower Manhattan.

But my big question still remains: if Romanticism is dead, the Disney gospel indoctrinates children everywhere with the message that “You can do anything you believe you can do,” and democracy is sweeping the globe, why this message that it takes an aristocrat to write truly great plays? There is something more than conspiracy theory at work here, I believe. There is a more subtle kind of elitism that can be revealed by a Structuralist analysis.

You see, the surface message of the movie appears to fit in nicely with a world packed with people’s revolutions in Egypt, Libya, Syria, and — in a more limited sense — Wall Street. It seems to speak to the masses’ discontent with “the present administration.” This superficial plotline is based on the obstensible reason for Edward de Vere’s anonymity: the movie reads the plays as covert anti-establishment pieces of propaganda. This accounts for the substitution of Richard III for Richard II; besides being a better-known play, it also presents a clear villain, a hunchback who could represent Robert Cecil and inflame the crowd to support Essex’s (failed) rebellion.

Well, then, you may ask, doesn’t that make perfect sense, here and now? Cecil could stand in for Hosni Mubarak, Moammar Gaddafi, Bashar al-Assad, or the current American antagonist — who is variously and vaguely defined as a Wall Street CEO, a corrupt bank manager, Congress, the President, or the Apple corporation (as the Occupiers vigorously tweet out their discontents).

But that’s not the real story. The real story is that Edward de Vere has no desire to overthrow the establishment. He only desires to step into a space in the establishment, preferably as king, but as merely the king’s adviser if that’s all he can get. He doesn’t want to change the system. He wants the system to remain exactly as it is, and to fit himself and his friends and relatives into the spaces in the structure. Were I writing in Colonial America in, say 1770, I would shout, “Tory!”

So maybe that is why this movie never made it to the top ten (and the weekend it came out, Puss in Boots was #1). It’s pretty, sure. It’s fun, definitely. But maybe the average movie-goers are smarter than Ronald Emmerich gave them credit for, and maybe they didn’t want to swallow elitism along with anachronism in a soup of weak conspiracy-theory. That is a lot to swallow.