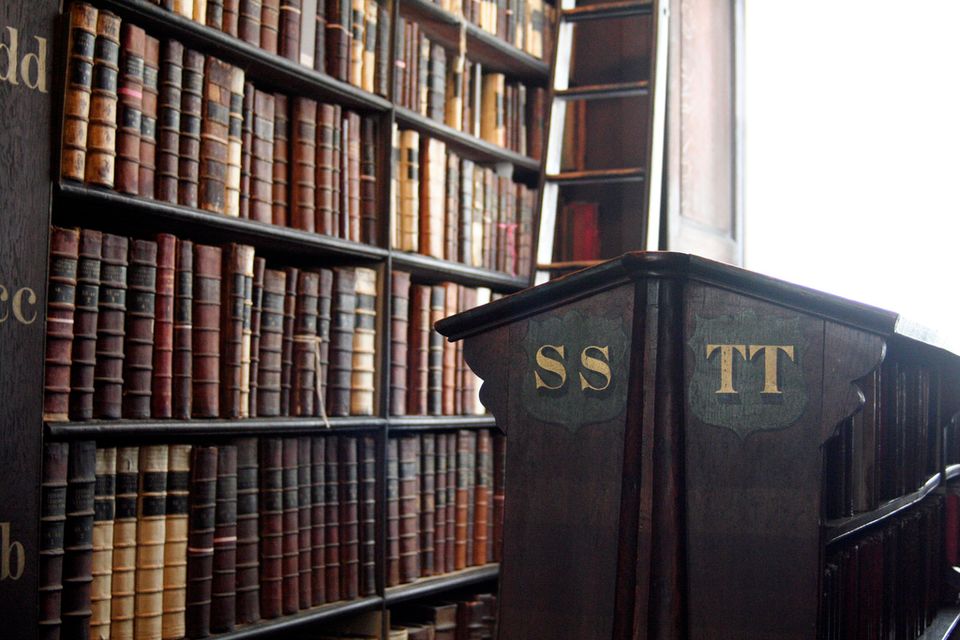

In a set of black-walled, dimly-lighted rooms in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Ireland, the history of the book unfurls. Chinese narratives, Japanese seasonal poems, Korans heavy with jewels, papyrus scraps of Biblical texts; calligraphy as lovely as flowers, hieroglyphics, Arabic scripts, Greek print, Latin typesetting; paper, linen, leather, silk…. The colors there rival Dead Sea blue and Grand Canyon red, unrolling on ancient scrolls, edged with a wealth of gilding and golden ink. Pass by the peacocks in their splendor; glance past the Dome of the Rock in its pride: Here is the treasure of the earth.

This impressive collection of print materials, gathered by an American millionaire and bequeathed to the Irish people, contains some of the oldest and most beautiful specimens of the art of the book. Yet I found that what caught my mind the most about this display was the postmodernity of it all. There were two aspects of the Chester Beatty exhibition that revealed to me the ancient nature of what we “Western” humans tend to consider our newest attitudes to texts.

First, the physical material of the book was honored as an art-object. There was no mention in any of the informational videos or the tour-guide talk that Chester Beatty actually read these books: He collected them to look at and to hold, as others collect jewels. He loved them because they were old or because they were beautiful. This relegates the text—that is, the content of the text—to a secondary position, subordinated to images (many of these book are gorgeously illustrated), or even a tertiary position, subordinated to images and to construction materials.

Many of the pieces were distinguished by their use of gold. One particular series of Chinese scrolls used golden clouds as transitions from one scene to the next, much the way PowerPoint uses a fade-effect to transition from one slide to another. Imagine that the next time you are in a sales meeting the presenter scatters gold coins in the air each time he wants to move from one pie chart to another; that is the gloriously prodigal effect of these scrolls. Others were noteworthy for jewel-encrusted covers, or complicated filigree carvings, or stamped leather bindings. Each was a physical treasure that would have cost a lot of money even if they were not old, or even if they did not contain literary art and wisdom beyond price.

Second, the flexible nature of the text itself put the postmodern novel to shame. The term “postmodern novel” has come to refer to a book that does funny things with the text. Perhaps the narrative is non-linear, or characters’ identities are fluid, or the reader takes a role in determining outcome, or it deconstructs metanarratives. Yet this designation goes beyond the ideological content of the work; what’s postmodern about these products is their “non-traditional” approach to its physicality. The words might be printed sideways, vertically, horizontally or backwards. The sentences might form shapes, or spiral around into or out of the center of the page. The book might include elements that depart from two dimensions, such as pop-outs, fold-outs or cut-outs.

The point here is that the most “non-traditional” of these devices are more traditional than the supposedly traditional book! The two-dimensional page, cover with horizontal lines of text, printed on pages made of paper, bound between flat covers, is just the tiniest blip in the history of the book. Indeed, what we think of as the standard book occupies merely a 400-year period (at most!) in the thousands of years of stone carvings, jade engravings, painted wood, rolling scrolls, folding scrolls, papyrus sheets, cyclical texts, microscopic texts, mirror texts, words on walls, words on clothing, words on signet rings and words on a grain of rice.

One particular item in the Chester Beatty collection illustrates the ancient nature of postmodern textuality with startling precision. It is a Koran. It is written on a very small scroll—perhaps four inches wide. When you stand looking at this scroll from above, you see an intricately decorated border surrounding a grayish page on which a few large white words appear. But if you take up a magnifying glass, you can see that the gray hue of the entire surface is created by the entire text of the Koran, composed in minuscule handwriting. The white spaces on the page, which are words themselves, are the blank portions in which nothing is written. The microscopic words (written in a period before the microscope, the magnifying glass, spectacles or eye surgery) slant in every possible direction, curving, looping and hatching the page with mind-boggling complexity. The entire Koran, then, is compressed onto a tiny scroll, creating a text-within-the-text effect that is itself a work of art.

The postmodern novel, then, does not really do anything new. It revives old approaches to suspecting, playing with and adoring the text. Readers who are afraid of losing “real books,” as they often call paper codices as opposed to e-readers, should take heart—or give up. Grandmothers have probably been bewailing the loss of the “right way” to read since the invention of writing. I can imagine a Roman poem bewailing the disjointed nature of the bound book when compared to the narrative ease of the scroll, or an aged Egyptian lamenting the ephemeral nature of papyrus, moaning, “When I was young, we put hieroglyphics on a cartouche where they belonged!” The Kindle, then, is nothing new: It is simply today’s momentary mutation in the long evolution of The Book. It is a technological art-object in its own right—smooth, beautifully proportioned—and its ability to contain thousands volumes is a baffling beauty, much like the squeezing of a whole Koran onto a thin strip of paper.

In fact, the monochrome, flat aesthetic of the common e-reader may actually have an effect that is the opposite of the postmodern suspicion of text and narrative. So many ancestors on The Book’s family tree flaunted their physicality. By stripping away the gold, jewels, illuminations, bindings, unfurlings, swirlings, textures, colors and smells of those forebears, perhaps the e-reader returns to a focus on the words themselves: what they look like, how they are ordered and—most of all—what they mean. The most precious pieces in that collection are a few bland, discolored scraps of papyrus, bearing the oldest known manuscripts of the New Testament. So just as what gets called New is really the Old returning again, maybe the Old comes back in the New in the best ways. Unlike Chester Beatty, when we collect tens of thousands of books on our modern devices, maybe we can actually read them.