Let me preface this by saying that I get strangely sentimental around the holidays.

The first reason for going was the food, and the second was the nightlife, but somewhere in the top ten reasons that I chose to vacation in New Orleans was to put my finger on the pulse of the town that was partly responsible for one of my most recent reads, John Kennedy Toole’s Confederacy of Dunces. Somehow, it seemed romantic and hilarious that there still might be a philosopher-slash-hot-dog vendor, like Confederacy‘s protagonist, certain enough about life’s secrets to wear a costume like that on Bourbon Street as well as lead a Crusade for Moorish Dignity.

It’s easy to be a critic in the mold of that protagonist, Ignatius J. Reilly, decrying and lamenting the ills of a society, all the while maintaining a log in your own eye. Within Confederacy of Dunces, hidden among the sermons and moral indignation of the protagonist were several lovely descriptions of a city that, despite its own odd collection of degenerates, was nothing other than immensely human. (And speaking of sermons, while I was in New Orleans, I was jarred awake at ten each morning by a megaphone sermon on the corner of Decatur and Canal relegating all sinners to hell.)

While it was fun to spy the oddities, eccentricities, and inequalities that Toole lampoons in the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, things have changed immensely since Hurricane Katrina. This makes it all the more interesting that it was at the movies, like Mr. Reilly in the novel, where I had a profound encounter with quite different piece of art during my stay.

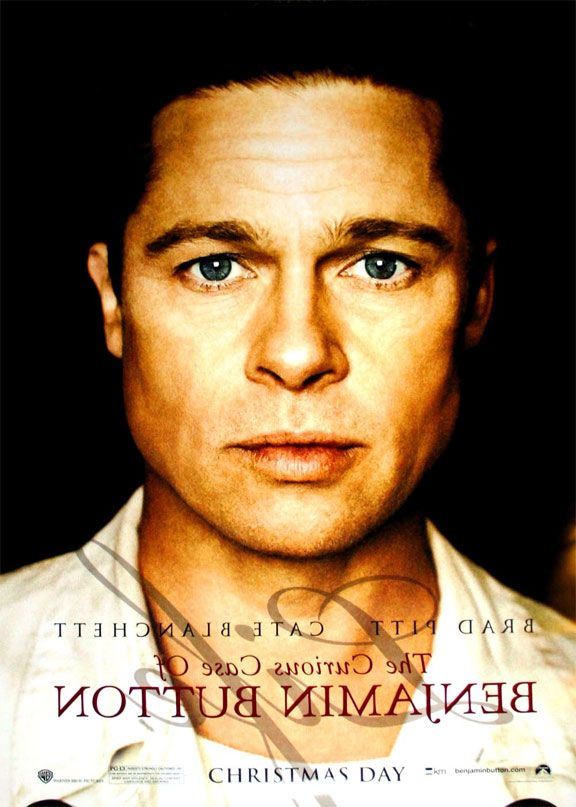

While I was sitting in the Canal Place Cinema on Christmas Day, I realized that the city of New Orleans was visible in its best light as Brad Pitt rolled through Gentilly on a vintage 1950’s Triumph in a leather jacket. Maybe it’s kind of ridiculous to say it, but New Orleans in the film The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, while not prominently featured, clearly shines through; the images portray the city as uniquely set in time and place, and as the film hints, possibly capable of throwing off the yoke of time when the situation allows.

Directed by David Fincher, the film chronicles the unique circumstances surrounding the birth, life, and death of Benjamin Button, book-ended with scenes from a hospital on the day Katrina made landfall. As you know by now if you’ve not been living in a cave over the holidays, Button ages backward. He appears to be eighty years old as an infant, and passes on as a newborn.

To me, the real story in the film was the city. It grows up and seems to lose its innocence simultaneously with Benjamin. As Benjamin grows younger, the city becomes also becomes younger, less mature. At several moments direct comparisons are drawn: New York is more affluent and artistic, but it is flighty and prone to change according to unimportant whims. Murmansk, Russia, while containing more seriousness, is at last too cold, the sameness of the place invading even the people that live there.

What other city would have been better used to display the timeline of the United States? The upper Midwest is a graveyard for what once was the nation’s industry. The West Coast is swimming in exposure, which only spotlights the notoriously absent soul of the place. The East Coast maintains an argument-winning intellectual leverage, an ardent belief in its own superiority keeping everyone else at arm’s length. All of these places have trouble changing, becoming other than their current descriptions.

Cities like Detroit, Newark, and Los Angeles have all experienced a knockout blow; New Orleans, a death blow. There is a strange blessing in this – instead of wheezing out an existence, ruin leaves a chance for a return, and therefore provides a blueprint of hope for the rest of America. As Walker Percy points out in his essay “New Orleans, Mon Amour“, the only city capable of delivering the American city from death by extremes of time and place is New Orleans. Early independence, spiritualism, hedonism, race struggles, devoted local culture, crass materialism, devastation, and hopefully, resurrection – it’s all there. New Orleans lives and still breathes. It stays up all night dancing. It best showcases the problems and hopes most relevant to the United States today, and despite how old it sometimes look, it constantly stays young at heart.

There was an ovation as the film ended, and as I left the Canal Place Theater there weren’t many dry eyes. I stepped out into the sunlight. It was warm and beautiful. It would have been a great day to be born in New Orleans.