David Denby has a good heart. He seems genuinely concerned for the men and women in American media and celebrity culture who find their reputations punctured by “snark,” those tiny, singularly inconsequential but collectively painful daggers that seem to fly from every corner of the internet these days. Vicious dress-downs are a necessary part of a healthy democracy, he admits, but do they have to be so ignorant and, well, so mean? Like yesterday, when Gawker writer Richard Lawson called Danny Gokey, arguably the best singer on this season’s American Idol, a “whistling idiot” who “whored out the untimely death of his wife at the preliminary auditions.” Was that absolutely necessary?

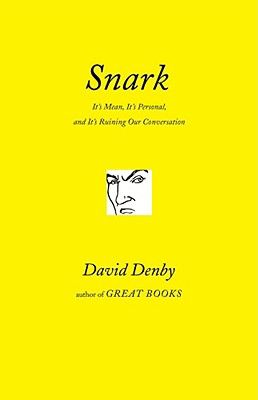

Snark, Denby’s defense of the world’s maligned couch jumpers, tries to give that kind of uncalled-for put-down a name. It’s “a strain of nasty, knowing abuse spreading like pinkeye through the national conversation.” Not “trash talk,” “satire,” or “nasty comedy,” but rather the sort of thing you read on Gawker or in Maureen Dowd columns: insult as “blood sport,” insult based on the crude philosophy that everything and everybody sucks.

Actually, that “sort of thing” may not exist. It’s rather impossible to locate a clear line where witty insult ends and Denby’s idea of “snark” begins. He spends a rather astonishing number of pages on what snark is not, and his attempts to give a positive definition are the book’s weakest passages. He glues together a daisy chain of examples: a feisty Wonkette post, a random Fox News headline, a Paul Begala remark in a fundraising email, a Perez Hilton graffiti job. Somehow because these all happened on the Internet, and not, say, in a closed-door meeting or scrawled on the wall of a bathroom stall, they’re evidence of a disturbing new idiocy that threatens to replace all serious thought and intelligent discourse. We all know anecdotal evidence is the number one indicator of a bogus trend story, and it’s just as telling in Snark, a book that manufactures a megatrend from scattered bits of valid insight.

There’s little debating that sarcastic Internet writing can be idiotic, lazy, and apathetic. It can target unfairly and deliver its punches clumsily. But Denby is wrong to dismiss it all-what ever “it all” is-as witless and effortless. He’s just as misguided to charge snarky writing with being inherently unimpressed by merit or success, unable to care or applaud when something happens to be praiseworthy. “Even when something original or great comes along,” he mourns, “snarking writers cannot turn off their attitude for a minute and celebrate.”

That’s not only demonstrably false, it’s a high-horse misunderstanding of the role “gossip” blogs play in the new media ecosystem. Gawker, Defamer and Wonkette are around to pick on the bad stuff, to peck at the liars, wannabes, and copycats. (Who are now, we should note, more ubiquitous and obnoxious than ever.) They’re not around to stage High School Musical-style celebrations of the latest breathtaking art or athletic achievements. Their bloggers appreciate a good film like anyone else (you’d know if you were on Twitter), but penning the thoughtful, wistful paean is A.O. Scott’s job. And point me to the posts where snark blogs ragged on Michael Phelps during the Olympics, or even after he was caught hitting a bong. (The Gawker post about Phelps’ mom that Denby cites is actually more of a snark on the silliness of endorsement deals than a rag on her “frumpy”-ness.) If I recall, even Gawker was pretty impressed with all those gold medals. So yeah, this alleged large-scale insulting of earnest, classy, talented people who are having their success and minding their own business? Where is it happening? Denby whales at the piñata, but doesn’t really connect.

When snarkers do attack, it’s not because they’re purveyors of an angry form of discourse that values cruelty as an end. Rather, it’s a means for expressing defeated idealism, for raving at the absurdity of entrenched institutions insults that insult our intelligence and sense of fairness. Underneath their “comically defeated” voice, as former Gawker editor Emily Gould described it, snark writers do believe in something-they just use their sarcastic jokes to dull the pain of constantly confronting a comically out-of-touch media and shameless celebrity culture. Instead of wondering why the “Manhattan party kids” are angry, and why their rage might be justified, Denby grumpily sends them to the corner for a time-out. You! You irrelevant little Gawkers! Go sit over there with the YouTube commenters and be quiet until you learn to get over yourselves. The grown-ups are trying to write.

This attempt to lump respectably talented young Internet writers with witless hacks like Perez Hilton encapsulates this book’s fatal flaw: its inability to separate the truly idiotic from the intentionally exaggerated, the inane from the ironically lowbrow. Too often, Snark tries to bundle divergent strains of public discourse-irony, idiocy, criticism, slander, libel-into one convenient little ball, then hurl it at whoever Denby happens to dislike. He distinguishes randomly and incoherently between media figures: Gawker rags without values, but Jon Stewart is a defender of civic virtue. Maureen Dowd “doesn’t have a single political idea in her head,” but Keith Olbermann is “intelligent as hell.” (All of the above, one could argue, are occasionally ruthless entertainers who attempt to illustrate the truth with sarcastic humor.) As a rule, his analysis makes sense in its most specific examples, but snaps when stretched toward grand theories.

More broadly, Snark is another tired argument against new media, an elitist rebuke cloaked in hip Webspeak. (Ironically, Denby’s obvious unfamiliarity with the everyday routines of the internet generation-instant messaging, Twitter, many of the blogs he quotes-casts him as transparently out of touch.) We heard this same line about talk radio, about Fox News, about people reading news online: the experts are losing control of the discussion. Snarkers react viscerally to the highbrow notion that intelligence and objectivity are sequestered in a few ritzy office buildings in Manhattan, and having too many voices out there-and God forbid having anyone compete for an audience-muddies the intellectual waters.

What Denby really wants, he says, is a civil discourse that values deliberation, nuance, and authority. He wants people to believe in things, to defend them passionately, and to insult their opponents honorably. But it’s unclear how attacking a vague concept like snark as inherently illegitimate-and dismissing all those who use it intelligently to express real outrage-really does anything to further those goals. Like a true old-guard alarmist, Denby insistently ignores the fact that people can read snark, have a laugh, and leave it in its proper place: lowbrow entertainment with the occasional incisive insight.

This article originally appeared on Patrol, a daily web magazine that covers the arts, culture, and politics in New York City.