Last fall, Lindsay Zoladz wrote a perceptive, sobering article for The Ringer. In it, she cites Speedy Ortiz frontwoman Sadie Dupuis on recent developments in indie rock:

The things that are most exciting for me are introducing narrative elements that aren’t atypical but just aren’t part of the canon—things that are normal to my experience as a feminine person. So I’m obviously the most psyched when I meet with a 13-year-old girl who reminds me of myself. But it’s also awesome when I see a 45-year-old guy who probably likes Pavement and Sebadoh and Guided by Voices, but is now connecting to a narrative outside of what was the onslaught in rock for so long.

I found this passage speaking to me, if for no other reason than I’m a (more-or-less) 45-year-old guy who likes Pavement and GbV. Like so many men my age, my thinking around gender and sexism has been challenged and has thus evolved over the past ten years. I’m grateful for that evolution, but like so many others, I have much yet to learn.

Perhaps an expression of that desire to learn can be found in the number of male indie artists who have brought women’s voices onto their records. I’m not talking about co-ed bands, like the New Pornographers or Los Campesinos. I’m talking about decidedly dude-centered, nerd-beloved artists. Spoon’s Hot Thoughts (2017) featured a quartet of women, including Sharon Van Etten, singing back-up and in unison with Britt Daniel on about a third of that album’s tracks; Rivers Cuomo was joined by Bethany Cosentino on “Go Away” from Everything Will be All Right in the End (2014); Stephen Malkmus gave a verse to Kim Gordon on “Refute,” one of the songs from Sparkle Hard (2018).

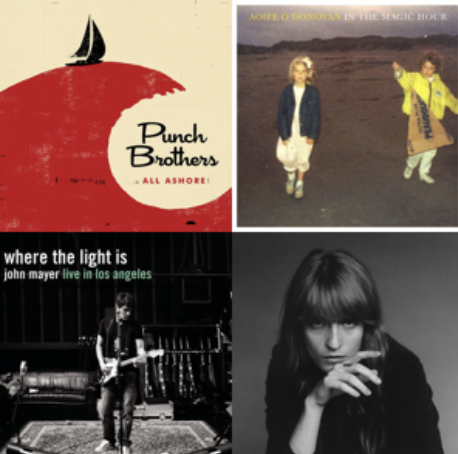

Three recent releases expand this guest-spot-for-a-lady into something more substantial: Better Oblivion Community Center’s debut album, Vampire Weekend’s Father of the Bride, and The National’s I Am Easy to Find. The first of these, Better Oblivion Community Center, is the most obviously egalitarian of the three. Conor Oberst (aged 39) has often worked with women, even back in the Bright Eyes days—most effectively, for my money, with Emmylou Harris on I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning (2005). But for this project, Oberst and Phoebe Bridgers formed a brand-new outfit. I don’t know who approached whom, but the two contribute to the writing, the playing, and the singing in what feels like a true collaboration. The fruit of that collaboration can be witnessed by the band’s performance on Stephen Colbert of “Dylan Thomas,” a rocker that gains in energy and joy when performed live.

Though apparently a loose concept record, Oberst and Bridgers operate as confessionalists in their writing and singing, their lyrics yoked to the personas they’ve adapted fronting bands. The songs are earnest; the narrators, if not Oberst and Bridgers themselves, seem to mean what they sing.

Vampire Weekend, on the other hand, are formalists. Father of the Bride, aside from featuring some of the most justly maligned album art ever to grace a major label release, is an aural production: The sound is king. I just don’t know what any of it means. Danielle Haim’s presence throughout the album is lovely, yet it also feels like one more element in front-man Ezra Koenig’s Wes Andersonian sonic landscape. (There are a lot of elements in that landscape, as the list of songwriters, producers, musicians, and years needed to bring it all together indicates.) Haim sings duets with Koenig (age 35) on three different songs, each of which hit on the sentimentally sketched, doomed-lover tropes common to Tammy & George records. The first of these, “Hold You Now,” is the best, but all three work within a type, no matter how advanced the songs’ sonic palette. Koenig is playing with different genres and themes on this album, and Haim’s been invited to play along.

To me, the most interesting of these new releases, and the one that has the most to say about our post-#MeToo era, is I Am Easy to Find. In the mid-aughts, a friend of mine suffering from an alcoholism I’d not detected mailed me a burned copy of Alligator as if in confession. The album’s mixture of suave self-confidence and harrowing self-interrogation made for intense listening. I enjoyed the music’s clear debt to the indie rock that came before it, and I admired Matt Berninger’s grim, muted, self-disclosing, and subtly emotional baritone.

While perhaps not as admirable as starting an entirely new outfit, a la Better Oblivion Community Center, Berninger (age 48) and company do something more unexpected on I Am Easy to Find: They revise the meaning of the band called The National.

Berninger’s voice and the singing style it inhabits become just one of the multiple (mostly) female voices who occupy the melodies and harmonies on the album. These voices express longing, comfort, wisdom and prophecy. Berninger still sings lead on many of the songs, but he just as often allows others the first, and last, word. In some cases, he disappears completely.

What initially worried me about this approach was my belief that Berninger might be projecting his own, male-derived point-of-view onto the women invited to sing with him, like a film director casting an ingénue into the role that suits his desires and fantasies. The first time I heard I Am Easy to Find’s opening song, “You Had Your Soul With You,” I feared the worst:

I have owed it to my heart, every word I’ve said

You have no idea how hard I died when you left

These lines, from the bridge, are sung by Gail Ann Dorsey, who sings with a calm, almost clinical authority in tension with the couplet’s heartbreak. The song’s lyrics, a symbolist take on the aftermath of a failed relationship, are not what I feared they were—that is, the projection of a tortured man who conceives of himself as being so vital that his absence leaves the secondary voice, the woman’s, bereft of hope or life. The song’s vibe is not swaggering or boastful. It’s bewildered. It’s a dialogue between two people trying to figure out what happened to them.

Indeed, the lyrics were written by the person Berninger is married to, the filmmaker and writer Carin Besser, who has been co-writing lyrics for The National since Boxer (2007). That arrangement may contribute to why (for me) the album works so well. There are songs here that are what you’d expect from the band at this point (“Quiet Light” is a sound I love, but it’s a familiar sound), but often the call-and-response of the vocals suggests a series of dialogues, or vignettes, drawn from a somber musical. Dorsey is joined by Eve Owen, Sharon Van Etten, Diane Sorel, Lisa Hannigan, Kate Stables, and the Brooklyn Youth Choir. Several of these people sing on multiple tracks. Dorsey sings on six, for example, and in one of the most striking instances, her voice arrives mid-stream to join the chorus of voices of “Where Is Her Head,” lending gravity to a song that in its delicate energy threatens to float away. (The number of singers also suggests another precedent: Hip-hop, where rappers and singers guest as a matter of course.)

The most powerful track on the album, “Not in Kansas,” has Berninger singing a lament for the things of this world in the age of solastalgia: eco-catastrophe, refugees, the alt-right, topiods, the retreat of the sea of faith—all as he resignedly leans into those pop-culture touchstones that bring him solace: Annette Bening, mid-period R.E.M., the voice of Roberta Flack. In rejoinder, a chorus comprised of Dorsey, Stables, and Hannigan appear like the aural equivalent of the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey, announcing a new paradigm where our cares—and maybe our existence—will be replaced by a new reality, by becoming, indeed, “a new creature”: “And the people all know that it’s over / They lay down their airs and they hang up their tiresome words.” The women’s voices offer a kind but firm rebuke to the man’s—and men’s—retreat into cultural arcana. Your knowledge of cultural references, boys, won’t save you. Look outward.

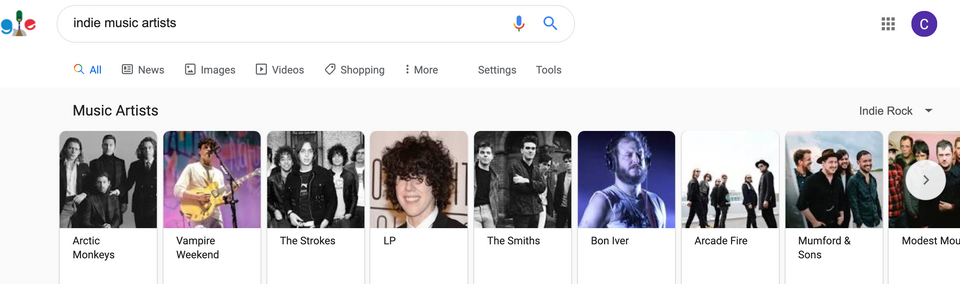

What The National, along with Vampire Weekend and Better Oblivion Community Center, reveal about the direction of the conversations around indie rock and sexism, I cannot say. I can’t imagine it moves the needle in any particular direction. The image below, captured from a Google search I did for this article, speaks for itself.

That image shows, beyond the obvious, that the term “indie” may simply be outmoded, given the relative age of some of the artists pictured. What is true, though, is that some of the most vital music of the last couple years has come from the likes of Mitski, Van Etten, Julien Baker, Solange, Tank and the Bangas and Lucy Dacus (whose Historian is a mighty document). Their music has been busy transcending and collapsing genre categories. Who knows if the dudes, and their tiresome words, can catch up?

[Post was edited 6.6.19 for clarity.]