“Genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at will.” —Baudelaire

In his essay “Exiles,” Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño writes, “All literature carries exiles within it, whether the writer has had to pack and go at the age of twenty or has never left home.” In the (often self-imposed) exile of the young writer, few wellsprings are as welcome as Bolaño’s fiction. His stories contain life.

Beginning to read Bolaño requires a certain posture; it is like being in a country, city or room where you do not speak the common language. His stories are littered with characters displaced from their origins: a Chilean detective in Italy, a Russian porn-star in America, a Chilean student in Mexico. Characters are placed in the unknown where the unfamiliar landscape naturally creates tension. Bolaño explains, “Sometimes exile simply means that Chileans tell me I talk like a Spaniard. Mexicans tell me I talk like a Chilean, and Spaniards tell me I talk like an Argentine: it’s a question of accents.” In these kinds of moments, exile encompasses external as well as internal landscapes. Not only can we not recognize the faces around us, but the very mind inside our skull seems strange and extraterrestrial. The foreign mirror of exile reflects the question: Who am I?

Bolaño’s fiction packs a peculiar jab, creating what Francine Prose defined as “microclimates” that obliterate everything outside the narrative. He crafts a universe fogged with the mysteries and paradoxes of a detective novel using deceptively simple prose. Bolaño’s stories are an expanse of complexities against an entrancing atmosphere, with sinister forms of evil casting shadows behind every sentence. Reading Bolaño, we become exiles in his universe.

Bolaño’s stories are an expanse of complexities against an entrancing atmosphere, with sinister forms of evil casting shadows behind every sentence. Reading Bolaño, we become exiles in his universe.

Bolaño’s fiction often focuses on youth, not just physical or temporal development, but an intellectual and spiritual coming-of-age. Youthful openness in Bolaño’s characters does not simply mean readiness for amoral promiscuity. Parties, sex and drugs happen as a part of youth, but these experiences are neither the heart of the matter nor merely outliers. They just are: experiences free of the over-interpretation that torments many of Bolaño’s characters, and many writers during the editing process. Herein lies an eerie paradox: Bolaño promotes openness that is both active and passive. Characters must be open to ethical demands, like a rescue or a courageous brawl, but that openness to act requires the contemplative stillness of a detective. Through the haze of eroticism, Bolaño promotes the kind of openness—both destructive and worthwhile—that so often thrives in youth but barely survives adulthood.

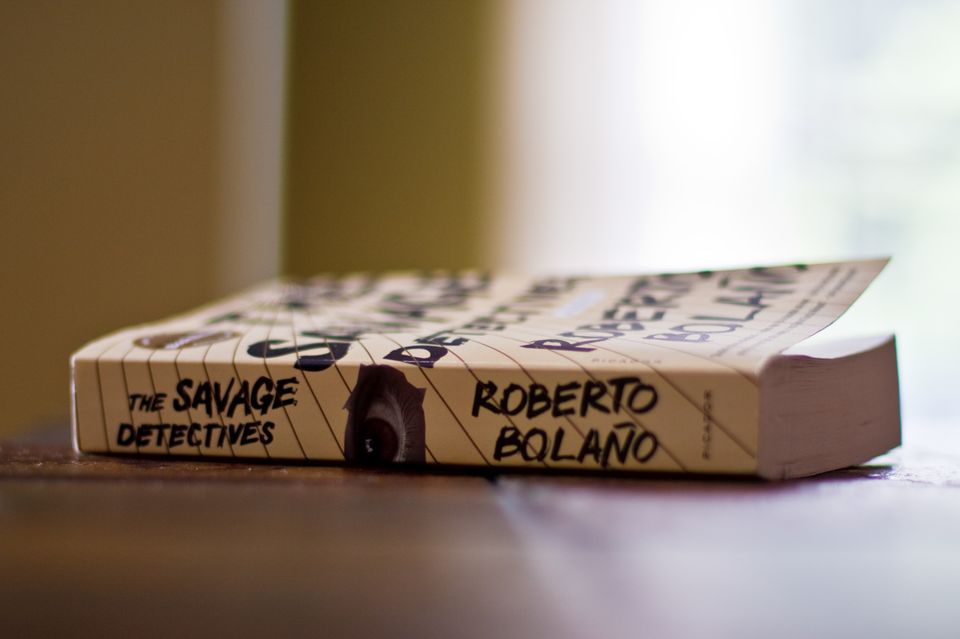

This particular openness contrasts with social aging: the slow, peer-encouraged disenchantment with one’s youthful aspirations. More often than not, fear dries up dreams. For a young writer (or any writer) failure is a guarantee. For the character in The Savage Detectives who claims, “Youth is a scam,” maturing means failing less and less often; it means giving up writing—the youthful mirage—for a more certain future with fewer mishaps. In comparison, Arturo Belano, even in his forties, could be described as immature. He has cut his hair but he is still immature. He has a son but is still immature. He has grown up but is still immature. Adulthood proves a difficult task: How does the writer converse with a childlike imagination continually while actively resisting the illusions there?

True artists in Bolaño’s fiction exhibit a childlike seriousness of play but still pause at the terror of uncertainties. Giving up a promising future for the writing life takes a kind of confidence and courage Bolaño maintained his entire life despite mounting hardship. What really matters for the writer, according to Bolaño scholar and translator Chris Andrews, is “to lose oneself more fully in the construction of an imaginary world, as children often do in play, while using the written word to stabilize that construction over time.”

Loss of self is key to genius: children are at their most creative in the self-forgetfulness of play, complete with frights, and it is this forgoing of self that is frequently lost after the coming-of-age. We become caught in a kind of voyeurism, watching ourselves from a removed, safe distance, addicted to over-interpreting details that push us further from ourselves with every thought. Bolaño thinks that we must become exiles of our own head, like children, to truly create. And herein lies the genius of his fiction: we leave the home of our head.

Therefore, confidence for Bolaño is not synonymous with self-assurance. Confidence is not the certainty of achievement, nor the denial of fears. Consider Ulises Lima in The Savage Detectives, who, along with Arturo Belano, leads a revival of the “visceral-realist” movement among Mexico’s young poets: When a fictional Octavio Paz asks his secretary to compile a list of the most important visceral-realists, even among the hundreds of names, Ulises Lima is not included. Lima is a failure if recognition equals success. True success, for Lima and Bolaño, is a deep, concentrated effort to exile the writer’s mind, to disappear from the anxiety of success.

True success, for Lima and Bolaño, is a deep, concentrated effort to exile the writer’s mind, to disappear from the anxiety of success.

In the end, Bolaño employs fear, failure and exile together with his subtle admiration of life. He encourages artists to return to a child’s unfettered imagination. As he writes in his iconic novel 2666, “The truth is we never stop being children, terrible children covered with sores and knotty veins and tumors and age spots, but ultimately children, in other words we never stop clinging to life because we are life.”