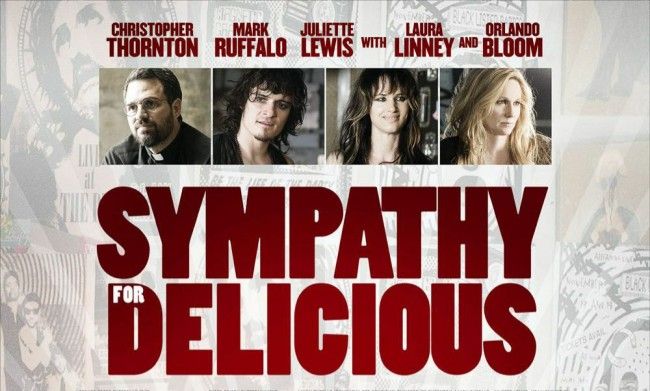

As Dean “Delicious” O’Dwyer whips along the streets of Sympathy for Delicious‘s hazy LA, one almost marvels at his practiced nonchalance in the wheelchair. It is hard not to think of Christopher Thorton, the actor playing Dean, whose accident years ago had landed him in a similar situation, prompting him to write the screenplay for Sympathy.

As Thorton did, Dean tries praying and even attends charismatic faith healings out of desperation. Dean’s disability has marginalized him thoroughly: a promising career as a DJ has been truncated, he lives out of his car and gets in line at a gritty soup kitchen run by another unfulfilled character, Father Joe, played by a stooped and woolly-voiced Mark Ruffalo (who also directed the film). Father Joe had envisioned himself building a sustainable “state-of-the-art shelter”, instead he’s stuck handing out temporary solutions due to lack of funding.

Here the real-life comparison ends as the film takes a turn for the surreal: Dean discovers that by touching others, he can heal anybody but himself. This additional injustice is a blow to Dean, and he initially lets Father Joe talk him into lending his “gift” cheaply at the kitchen, where the majority of the guests needs healing in some way. It is an instant crowd draw, but tensions escalate after the two disagree on Dean’s payment in light of the sudden surge of donations to the kitchen.

After falling out with Father Joe, Dean is accepted as a turntablist for a rock band headed by a glamorously skulking front man (Orlando Bloom). He is quickly resigned to the fact that he isn’t actually wanted for his spinning skills; his healing is paraded as a sensational side-show at concerts, the band’s shot at reviving the euphoria associated with rock legends. Dean’s grimy undershirt is replaced by leather chokers and tar-black nails as he pushes epileptics dramatically into mosh pits. When an attempted healing goes awry, he is ejected back into reality.

Sympathy is a contemplative and determined study of the “Why Me?” question, that strange universal fist-shake. The film explores human coping psyches and the possibility of faith and fate. It is dangerous to build a story on philosophical aspirations, not least because one runs the risk of burying the characters underneath the strain of introspection. The results flicker in Sympathy. Dean’s pre-accident life is only ever mentioned in conjunction with lamenting his would-have-been career, and Father Joe’s character and motivations are sadly as obscured as the spectacles through which he blinks. Orlando Bloom and Juliette Lewis both look like they’re having fun playing slurred rockers, but it feels more like a feather boa-ed, fish-netted game of pretend.

When the film does shine, it is poignant. Thorton and Ruffalo tackle the abstract cleverly by going for the surreal, especially when portraying the rock and roll healings. In one scene Dean asks Father Joe if he could really be healed. The Father replies enigmatically, “entirely possible.” Whether intended or not, it is a candid commentary on the church and how it deals with suffering. Father Joe seems to be speaking in priestly double entendres; he’s implying that whether or not Dean’s body could be healed, his soul always has a chance. The idea brings hope, but oftentimes overlooks the individual pain. In the end, Thorton puts on a courageous face towards understanding the mystery of this pain, and the search is both well-worn and admirable.