It’s taken me a while, but I think I figured out why no one wants to play video games with me. I’ve gathered some evidence, too.

Exhibit one: Left 4 Dead 2

Four survivors try to make it from Savannah to New Orleans, traveling through entire regions infested with zombies (“infected,” in game terminology). This is a first-person game, so players see things from the point of view of the characters and have to work together if they want to actually make it to safety. The game’s designers did a good job of fleshing out the locations, from a shopping mall to abandoned amusement park to the French Quarter. The game pays a lot of attention to detail, and many of the locations feel like real places (albeit ones with shambling undead) — atmosphere, I think they call it.

So I’m playing online with some total strangers, all with colorful handles like [aw3s0m3z] YOUR MOM or Linkinpark4evr (my name: Toes). These are folks that’ve been playing the game constantly since it was released last year, and they know every trick, have every corner of every level memorized. They know that if you stand on that ledge over there, you can shoot through a graphical glitch in the wall without having to worry about zombies nibbling you.

Anyway, we’re playing a portion of the game that involves wading through a flooding town in Mississippi, and an ongoing storm aggravates the zombies. Hundreds of the monsters are rushing toward our characters, and the other players are tactically racing through houses, yard sales, and playgrounds to make it to the safe spot at the end of the level. And oh lord toes were are u y are u lagging behind?!?!?!?! It’s because I noticed a bookshelf in one of the rooms, and paused to see what titles — fictional or not — the game developers placed there.

Thinking I’m getting attacked, one of the other players falls back to see what’s holding me up. The zombies catch up. We lose.

Exhibit two: Age of Empires II

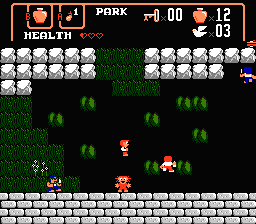

In this real-time strategy game, players control one historical civilization (Turks, Celts, etc.) and build a society while battling other players. Even though it’s over a decade old, Age of Empires II summed up these cultures nicely, with everything from the increasing architectural strides the cultures would make to the comments your little worker people would make (in the various languages and dialects!) when you ordered them around.

I would occasionally play against guys in my dorm when I was in college, and while the rest of my friends were scurrying to built the best warriors faster than the rest, I would hum to myself and work on building nice town squares or thinking of effective ways for my townsfolk to work on their carpentry skills. I was always the first one out of the game, my town reduced to cinder. The one time I tried to fight back didn’t really work, either; I was playing as the Persians, and I thought it was really neat that I had war elephants. They were pretty powerful, from what I’d gathered, so I gripped my mouse harder than I probably should have and started training lots of elephant units. War elephants, baby!

Dozens of war elephants, ready to attack. I sent little troops around to scout out the map and soon learned that another player — the one cocky guy down the hall — was awfully close to my town. So I sent in the elephants, an almost comical swarm of swinging trunks and computerized trumpeting sounds. As the creatures starting plowing through the other player’s buildings, I typed something like “I’ve come for your peanuts” into the game’s chat function. His momentary panic quickly shifted to something more stable as he rallied his troops and not only wiped out my elephants, but then invaded my (defenseless) village. I lose.

Exhibit three: Dungeons and Dragons Online

Dungeons and Dragons Online — DDO to us nerds — is a recent computerized incarnation of the enduring pencil and paper roleplaying game. It’s a massively multiplayer game, so there are thousands of other people running around the fantasy world, interacting with you, trading with you, teaming up with you (or not doing any of these, in my case). There are numerous quests that players can take part in; characters advance through the game at a snail’s pace, though, and sometimes players will find themselves running through these quests multiple times out of necessity.

While all of the game’s quests are designed with story in mind, it’s easy to ignore that and just run from point A to point B as fast as possible to nab the treasure or experience at the end. I occasionally play with a few friends, and most of them have learned which quests yield the best rewards. They’re rushing through these quests, pausing only to fighting the monsters they need to fight and move on. I’m usually at the rear of the group, trying desperately to read the text that advances the plot, and end up desperately (mis)typing something like “Hey guyts wait up!! I’m trying to reaad all of the story!” Which then usually leads to me getting lost, eventually spotting something cool and thinking, “Hey, a haunted grotto! Sweet! I wonder what’s in there?” And then I die, and lose.

Conclusion

Playing video games online with other people usually involves boiling the experience down to simple actions. Make it to the escape area and shoot zombies. Quickly train soldiers and win. Get treasure and level up. Stopping to ponder, well, anything is frowned upon. Left 4 Dead 2 is more than just another shooting game because it takes the time to weave in nuances, be it the deft banter between characters or the subtle social commentary. I don’t think I can turn off the part of my brain that recognizes this, though, and that makes me a lonely online gamer. Winning, for me, is taking part in a story or being awash in near-tangible atmosphere, not just getting a lot of points.

This is an area that I think will be crucial in making video games more respected artistically. As fun as herky jerky escapism is, it leaves me feeling empty. While game designers and programmers might be crafting something worthwhile, it’s easy for the gamers on the other end of the screen to tear it all down. Maybe we’ll take the time to smell the digital roses; maybe, this way, we can win.