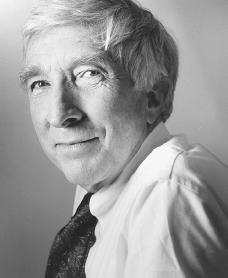

I can’t claim to be John Updike’s biggest fan. I’ve only read a couple of his books. But I was perturbed to learn of his death this past Tuesday. For this California boy, he represented the leather-patch-on-the-tweed-jacket kind of writer – a WASPy New Englander who snapped away on his Underwood and smoked unfiltered cigarettes. Anyone who made their living writing was, for me, someone to emulate. But for would-be writers like me, the iconic imagery that surrounds real writers blows away like so much fog (or cigarette smoke) as one gets older, and leaves only what you can glean from the work. This is as it should be, of course – if you’ve actually read the books.

The 76-year old novelist, essayist, short-story writer, poet, and critic’s place in the pantheon is unassailable. Two Pulitzer Prizes, a PEN-Faulkner Award and a host of other prizes cement his legacy as one of the great white writers. And while I’ve read a few of Updike’s novels and some of his critical essays and poetry, the book that sticks most to my ribs is Rabbit, Run, which I read a few years ago.

More than 40 years after it was written, Rabbit, Run still seems as fine a portrayal of helpless masculine angst as ever there was. Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, the has-been prep basketball star: making all the wrong decisions, listening to bad advice, and fleeing neurotically at the first sign of emotional distress, was a true everyman – more like myself and most guys I knew who were confronted with relationship troubles without the requisite skills or preparation. Bouncing between his demanding and very pregnant wife and an obliging (at first) prostitute named Ruth, the hapless Rabbit leaves us, as the title suggests, fleeing from his life and the mess he has made of it.

In 1976 Updike saw his own first marriage fall to the divorce decade that was the 1970s. His name-making book Couples (1968) presaged the tone of the swinging seventies amongst the married – at least those in the art world. The titular couples spawn a whirlwind of sexual exploration and selfishness that was one of legacies of the 1960s, while a lingering cloud of guilt surrounds them. Given the divorce rate then and since, perhaps art does imitate life.

Updike remarried the following year, and remained married until his death. While his most acclaimed work was published long ago, his 15 minutes of real fame came with the film adaptation of his 1984 novel, The Witches of Eastwick. Never particularly comfortable with fame, Updike avoided the maelstrom of a Hollywood production as best as he could. The novel was purportedly a response to persistent feminist criticism of his fiction, so the hostile response from feminists was perhaps not surprising. It is not hard to see the novel’s gleeful trio all sharing (and ultimately being bested by) one male protagonist as more than a bit of nose-thumbing at feminist attacks, though Updike denied this connection in a Telegraph.co.uk piece.

But perhaps the most important Updike legacy is the sheer volume of his work. More than twenty-five novels (including a Witches sequel published last year) and many more volumes of stories, poetry and criticism garnered many awards, though, alas, no Nobel Prize. It became easy for readers to take him for granted; you might browse the reviews of his books as they came along, knowing you already had enough of his back catalog to wade through.

And so procrastination raises its ugly head. In his introduction to the Everyman’s Library collection of the four Rabbit Angstrom novels, Updike says the books became a sort of “running report on the state of my hero and his nation.” I don’t know about that, but I do remember loving that first one. Rabbit stands as a kind of touchstone for American men feeling battered and buffeted by modern life (read: most of us). And the approximate ten year span in real and fictional time between the books appealed to the procrastinator in me; my plan was to read the books in the same time sequence – one every ten years. Checking the copyright page, however, I appear to be about four years overdue in reading the second book.

I’m also delinquent in reading the second book of Angstrom’s literary descendant Frank Bascomb, hero of Richard Ford’s The Sportswriter and Independence Day. I did enjoy Sportswriter, finally, though Bascomb’s wishy-washy, ambivalent moodiness nearly made me put the book down prematurely. So now it will be back to the Everyman collection, after I’ve finished Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy. Maybe Independence Day after that. You can only put things off for so long, you know: before you know your time will be up.