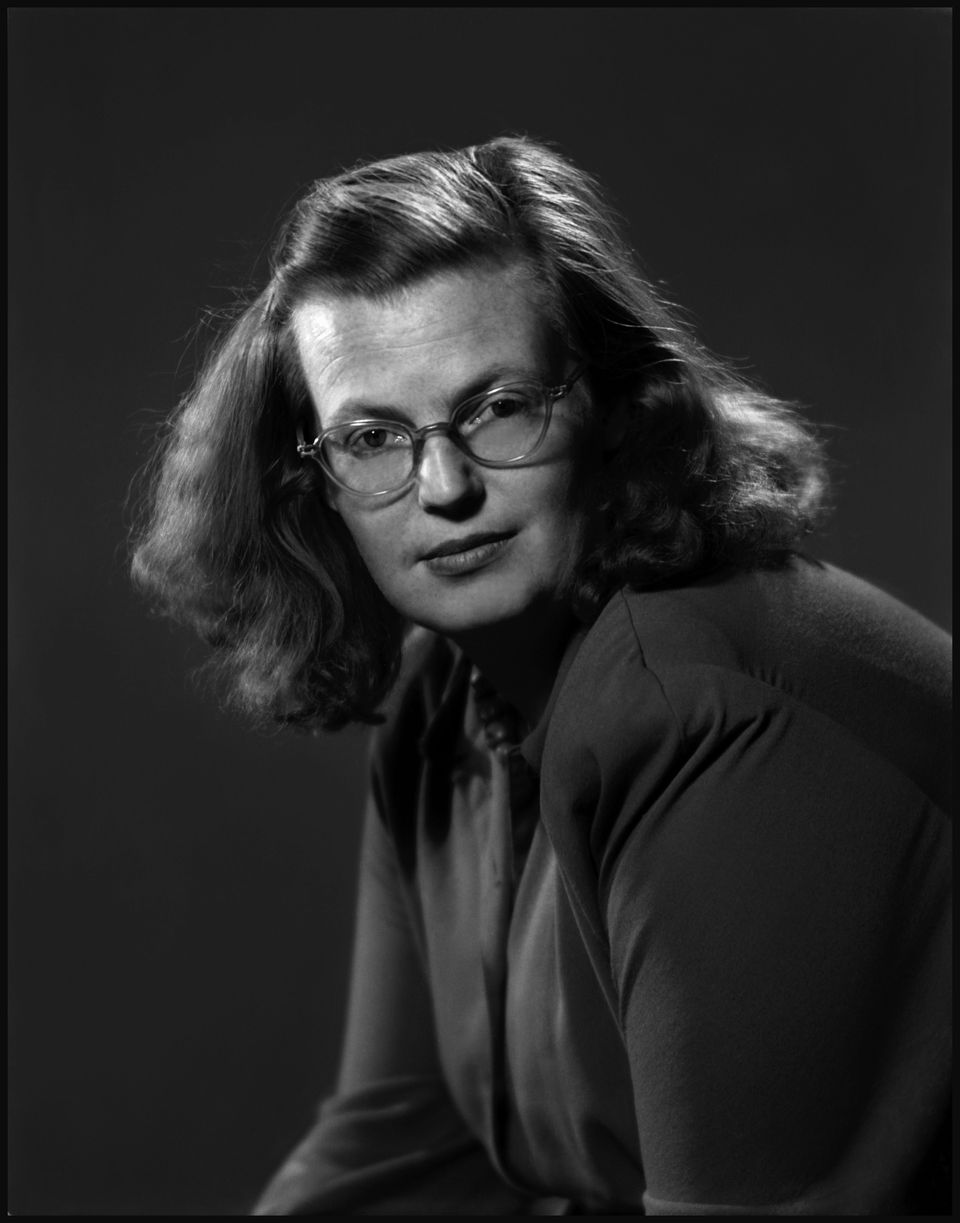

In the classic supernatural thriller The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley Jackson writes,

“‘Don’t do it,’ Eleanor told the little girl; ‘insist on your cup of stars; once they have trapped you into being like everyone else you will never see your cup of stars again.

It was this basic fear of conformity—the prospect of becoming someone else’s idea—that compelled Jackson to divulge not only the supernatural but the wickedness of the everyday. To read Jackson is to dismantle the familiar and become on nodding terms with the void that will gladly take its place. With an unerring eye that exposed the macabre in domesticity and domesticity in the macabre, Jackson achieved a body of work that continues to validate the harmless eccentric.

Many of Jackson’s stories are written with alarming simplicity resonate the works of Raymond Carver and Ann Beattie: stories so deceptively minimal the reader initially feels cheated and remains so until she returns to those curt, stripped down sentences and discovers their enchantment. Unlike the stories of Carver and Beattie, which are heralded for their linear simplicity, Jackson’s stories read like Hitchcock gazing out of one of Hopper’s windows, projecting the loneliness and suspense of the times with all the wry humor that ignites our curiosity. Whether faced with film or prose, it takes courage to fully embrace characters living in a world of their own making, particularly Jackson’s characters, which center their readers in the drifting emotional mist.

The Lottery

Jackson wrote over sixteen works during her short life but only one story continues to hold such subversive impact. First published in The New Yorker in 1948, “The Lottery” is now the most widely anthologized American short story of all time and a staple of school curriculum. Yet, outside the used literature books crafted for the middle and high school classroom exist stories too risky for the syllabus. A prime example of this being the formidable reaction to the publication of “The Lottery,” an act that both undermined and mythologized one of America’s forthcoming influential writers.

![Lottery_Image_1[1]](https://curator-magazine.ghost.io/content/images/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Lottery_Image_11.jpg)

Initially, “The Lottery” was received more as an insidious platform than the tour de force it is championed as today. To the surprise of Jackson and the editors of The New Yorker, “The Lottery” was subject to relentless vitriol and arrogance regarding the author’s intent. The mass, brutal reactions toward “The Lottery” are laughable today but the shameful aspects of such Salem-like judgments are undeniable. When the collective fears of a subculture are not addressed properly, well-meaning people may turn to the seductive lure of fable and conjecture. But what’s rarely addressed concerning the critical and cultural reception to such a work is the devastating toll it took on Jackson as a writer.

After The New Yorker debacle, the conflicting fear and dream of all writers was, for Jackson, in full tilt: the realization that total strangers are reading your work and doing so candidly. What made Jackson’s experience so unique was the writer-sized pigeon hole it left her in the aftermath. After all, such cataclysmic success is like an ill fitting coat of many colors. It drowns the artist and eventually the coat itself is all anyone chooses to see. The artist once capable of many hues is now imprisoned by the lurid fabric of unexpected grandiosity. It is the most devastating of exits.

The story that, for better or for worse, transformed Jackson into a literary icon was likely inspired by North Bennington, Vermont where she and her husband lived for the majority of their adult lives. As the wife of a literary critic and unapologetic egoist, Jackson lived a double life determined not by the ungovernableness of the psyche but by a hostile village of people that one would assume could exist in solely, well, a Shirley Jackson story. Naturally, Jackson was quickly assailed by insular, small town mentality and the young writer was often accused of elitism, paranoia, and the more titillating: witchcraft.

In an early biography she was described as an amateur witch, a possible publicity stunt that eventually functioned as a double-edged sword for Jackson considering she could never rescind the mischaracterization of her own writing. There was even a rumor she used a broomstick for a pen. In actuality, the only broomstick Jackson used was the one she wielded across the floor to renounce the dirt of the day-a day full of herding small children from dinner tables to bathtubs before sitting down to enjoy the solitary pleasures of writing. Although many of Jackson’s themes match those of upscale horror writer Patricia Highsmith, Jackson’s revelations focus on how hierarchical fixations alienate those who choose to wear spectacles of a slightly different colored lens. This specific type of alienation is perpetuated by a gloomy realm that denies the shared parts of human darkness and persecutes others for their differences. Such treatment is even bestowed onto children.

We see this in Eileen, the speculative teenager in the story “The Intoxicated”, who is writing a paper about the future of the world. “I don’t think it’s got much future,” she laments, “at least the way we’ve got it now.” The older and nameless male narrator of the story dispassionately tells Eileen that girls her age would be far happier if they traded Caesar for magazines and worried about nothing but “cocktails and necking.” The narrator caught between something carnal and paternal and forever doomed to say the wrong thing, is sympathetic in Eileen’s eyes.

Jackson’s Young Women

Young women in Jackson’s stories are either good, know-better souls like Eileen, or crypto-feminist icons like the indomitable Merricat Blackwood in We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Their diluted sexuality is like a botched fresco restoration glossed over to the point of caricature with all the original foundations underneath as raw and present as ever. Because sex is so remarkably absent in Jackson’s stories, it exists in all the spaces it has been denied. This, however, does not mean Jackson’s heroines are meek. These girls, feral in spirit and on the cusp of adulthood, confront the gritty realities that await them and ignore the trajectories of a more sedated human experience. It is their failure to compromise that ignites the hostility of those undeserving of their trust.

However bleak the lives of Jackson’s young characters may be, there are factors that render them victorious. Through disassociation cradled by a rich inner life, children can achieve a sort of cryptic independence free from adult scrutiny. These same children, however, are not free from reaching conclusions grounded in the external. Due to the burning loneliness of childhood experiences, it’s easy for a child to view the grim subtleties of the world in high relief. But children do not reach such conclusions on their own, and there comes a time when the adults who once chiseled away at a child’s life must accept these conclusions with dignity and grace.

Jackson’s characters, particularly her young heroines, seldom encounter a supportive elder brave enough to face them. What they find instead is the power to take the ordinariness of evil and reveal it for what it is: pervasive and extraordinary.

In Jackson’s work the inability to conform trumpets alienation. It is an inevitable occurrence that will cast shadows onto the world that tries to suppress the peculiar. For the sake of human intimacy, let us be content with all Jackson has given us. May we toast her wicked ways, the cups of our choosing running over plenty. As Merricat Blackwood tells us in the opening of We Have Always Lived in the Castle,

“I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had.