by Shemaiah Gonzalez

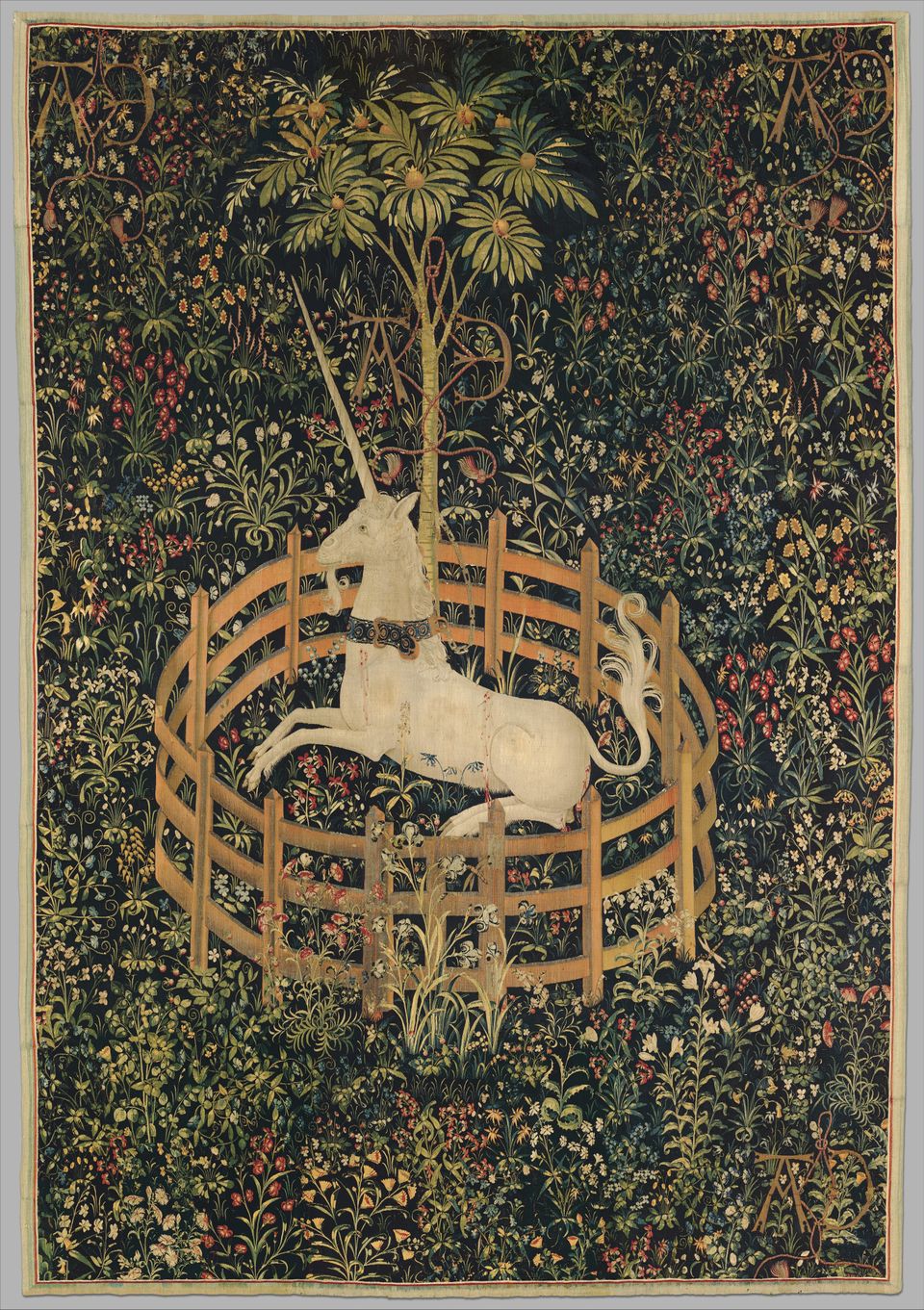

There is an audible gasp as each person walks into the room. Conversations started are now cut off. Footsteps soften. Although it is not a church, there is a sense of reverence in this space. In this room there is sanctuary.

Seattle artist Barbara Earl Thomas transforms paper, glass, light and shadow into a radiant chapel. Walls fashioned from cut white paper let light shine through in a glorious lattice of yellows and whites. The sliced shapes cut into the paper are geometric but also include voluptuous bodies, nearly genderless–full, complete, content. The result is luminous. The room, filled with light and awe, becomes a sacred space.

Garfield High School, where Thomas attended, is within walking distance of my home in the Central District, a historically black neighborhood in Seattle, which boasts an artistic legacy that includes Quincy Jones and Jimi Hendrix. Thomas has deep roots in this neighborhood, city and state. She received both her BA and MFA from the University of Washington studying under renowned artist Jacob Lawrence.

Thomas’ chapel is an invitation: she asks, in an interview with the Seattle Times, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful to create a space that would allow the viewer a change of world in order to experience whatever … I have opened them up to feel or think about.” There is something especially restorative about art that needs its audience to complete its intention.

In the same interview, Thomas explains the exhibit’s approach: “If you want to deliver a message or have people understand something that perhaps is not native to their system, you have to give it to them in a way that you can hold them while they can think about some hard stuff.” Art speaks a language we are more open to listening to and this space, a sanctuary, a place that provides safety in a difficult situation, transcends the space where we have previously heard the message. Thomas’ call? To rise above the perilous landscape of race relations and find a transcendent solution.

The paper Thomas uses in this exhibit is actually Tyvek, the synthetic material you might have seen a house wrapped in during construction. It is less akin to the texture of paper and more like the plasticity of thick vellum. The warm light that floods through invites us to find hope, beauty, grace and truth. It is an invitation to reconciliation.

The hallways leading in or out of the sanctuary showcase portraits. These too are cut paper but this time they are placed against a hand printed color backing. The palette pairs black against the kaleidoscope of a rainbow. The portraits are reminiscent of the art projects many of us created in elementary school, where we layered black crayon over colored paper, then scratched out a drawing in the crayon.In this more sophisticated rendition, young black faces peer out from the cut paper.

Thomas used her friend’s children as models for the artwork. Not only did she know and love these children, but she got to know their faces intimately as she engraved their images into the paper. Perhaps this was Thomas’ intention, to move away from the narrative as a whole and look at the intricacies, intimacies, tiny cuts, shards in the faces of children and consider how these narratives affect individuals, how they affect real people. Thomas said she wanted to explore our perceptions of other people and what happens “when we encounter a face.”

St Augustine taught that true freedom is not choice or lack of constraint but being what you are meant to be. For humans, created in the image of God, true freedom is not found in moving away from that image but in living it out. Thomas’ artwork reflects that image in the beautiful faces of black children. This art invites us to encounter that Imago Dei, reflected in those around us and in ourselves, in a way that compels us to be more like God. Faced with Imago Dei, what is our response? Do we dare hold the gaze? Do we engage it?

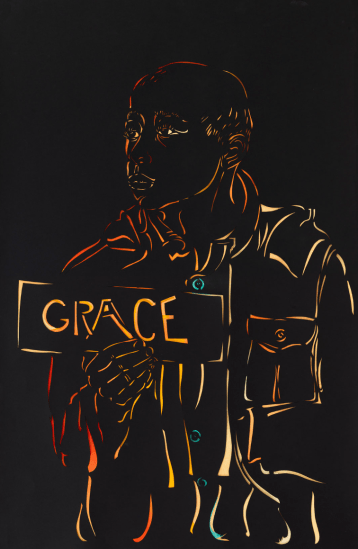

In another image from the show, Grace, Thomas again changes the narrative of racial tension in America. She plays with images of Black men holding signs reading “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot.” These images dominated the nightly news and Black Lives Matters protests after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. This time, we see an image of a young Black man holding a sign that reads “Grace.” Thomas says, “Grace gives you an opportunity to change an outcome.” What would it look like to offer grace to each other? How would we be transformed by this gift of grace? Would we then want to extend the same grace we have received to others?

Thomas expands the narratives of our racial landscape. When so many conversations on race build in tension or altogether end, Thomas’ work expands the story, giving it space to breathe and soar. Can we create a new narrative? One of transcendence? Of redemption? One that sees and honors the beauty of the Creator within each of us? One that offers grace? One that heals?

I want to answer Thomas’ luminous invitation with a resounding Yes!

About the Author

Shemaiah Gonzalez (Contributing Prose Editor at the Curator) has published in Image Journal’s Good Letters, Ruminate, Barren, Ekstasis Magazine, among others. After earning degrees in Literature and Theology, she is now finishing up an MFA in Creative Non-Fiction in Seattle.

Like this essay? Read more of Shemaiah Gonzalez's writing...