“Do what?”

“I need you to beat that table with this chain,” said Nate, draping it over my forearm. It was studded with metal fragments, pieces of chainsaw blade, and nails. “It’ll make it look nicked and, uh, authentic,” he snickered.

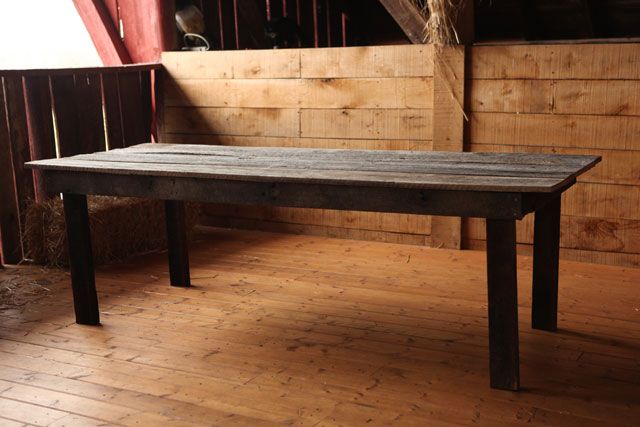

Nate was my brother-in-law and I was bumming around in his woodshop a few days while our wives visited and superintended children. He sold furniture to stores all over California and even moved a few things through the Sundance Catalog. The table was constructed of big-boned barnwood he’d salvaged from a chicken farm. Aluminum from the barns had been wrangled into picture frames stacked on a bench in the workshop. The ceiling joists had been trucked up to a winery in Paso Robles. One of the doors leaned against some pallets outside, awaiting metamorphosis into a desk. And some of the wall studs had been planed, joined, mortised and tenoned into this pine table some twelve feet in length and as solid as an aircraft carrier. The planing had cleaned up the splintery, aged faces of the wood and the old-growth pine boards gleamed in the peculiar California sunlight pouring through the shop windows.

“It’s too clean now. But you beat it up and the guy who buys it will think it’s an antique and pay another thousand for it,” Nate explained. He shook the chain. “Go make me some money!”

I hefted the chain and swung it at the table like a biker taking out an unsuspecting member of a rival gang. It rattled across the surface and the nails and chainsaw pieces bit fast into the wood. Extracting the weapon, I examined my work. In just three seconds I had added forty years’ worth of hard-won experience and poignant memories to about two square feet of the tabletop. The center board had a terrific gouge from where a chainsaw tooth had torn up a chunk of pine from around a nail hole.

“Ease up a bit, man,” Nate drawled, preparing a finish in the opposite corner of the shop.

“Gotcha.”

That initial stroke, I decided, represented that unforgettable Thanksgiving when Uncle Clarence emptied the Ballantine’s into his Coke and started drumming with the bottle. The rest of my work would portray in effigy the daily dimpling and scratching of the table in the regular course of family life. Squirming brothers not eating their brocolli. A giggling sister tipping the flower vase on its side. The mischievious cousins jumping up and tapdancing on it. Grandpa putting up his boot-clad feet while telling a Navy joke. Dad rebuilding an alternator on it because the garage was too cold. So I circumnavigated the table, wielding the power of decades until arriving back at the site of Clarence’s Thanksgiving spectacle. To finish, I stepped back, swung the chain over my head and let it go. It crashed over the opposite side of the table and pulled itself down over the edge, clattering on the concrete floor.

Nate walked over. “Good work. Now run over it with a palm sander.”

A couple days later we ran to a store in San Luis Obispo to deliver a pair of bathroom vanities built and beaten in like manner to the table. We dropped them off at the loading dock behind the store, where a tall woman in a sun dress and twenty bracelets on either wrist greeted us with an excited little clapping gesture. Nate and I hustled the vanities inside a stockroom and returned to the loading dock. She handed him a roll of hundreds. “Thanks for coming in today!” she said.

“Sure,” he said, and pocketed it without counting it. “This is my brother-in-law, Brendan.”

She turned to me and stuck out her hand for me to shake it. Her sun-darkened skin set off starkly against her straw-colored hair. “Nice to meet you! You know, people just love your brother’s work! I just can’t keep it in the store!”

“I’ll bet. It’s good stuff, isn’t it?” I smiled back.

She turned back to Nate. “See you next week?”

“Yeah, got a table for you,” he said.

She gushed excitement and waved at us from the loading dock as we climbed back into the truck. “Can we have a look inside?” I asked Nate. “I’m just wondering what kind of place sells your stuff.”

We parked in front of the store. The signage declared that its business was “antiques and vintage furnishings”. Inside we were greeted by one of Nate’s tables, an eight-footer, upon which sat dinner settings cobbled together from the studios of local potters. No two pieces were the same shape or color. Inside an oblong soup bowl I found an artist’s statement about letting “old-fashioned, natural imperfections shine” and a price tag of 38 bucks.

Nate caught my eye and flicked his finger at the card set on his table. “Authentic antique wood farmhouse table,” it read, “reclaimed and restored by a local craftsman.” Then I found the price. I would say that the twelve-footer I’d wailed on involved maybe twenty dollars’ worth of materials and two days of labor and finishing. This eight-footer of the exact same provenance cost $3,000.

The sun-and-straw saleswoman was speaking to a couple by another of Nate’s tables in another part of the store. We eavesdropped.

“Isn’t it beautiful? Look at all the nicks and notches!”

The wife nodded. The husband stared at his phone. His thumbs tapped on the screen, his brow furrowed.

“What I love about these old tables is how… how solid, they are. They just really knew how to build them to last. And it’s just the kind of table people just want to be around.”

“It would look lovely in the guest house, wouldn’t it?” The wife turned to her husband.

He shrugged and returned to his thumbing. “Why not?”

“Well, what do you think? Should we put it in the main dining room?”

She touched his arm. His hands dropped to his sides and his shoulders slumped. “Sure. Look, the house is your thing, okay?” he grunted, defensive, like he’d been accused of something.

She glared at him a moment, puzzled.

His phone rang and he dropped his eyes. “Gotta take this. Go ahead and get it.” He walked for the door and put the phone to his ear, his countenance transformed. “Where you at, man?” he laughed, stepping outside.

The wife watched him leave and turned back to the saleswoman. “So, I guess we’ll take this one.”

“I think that’s a wonderful choice. Such a warm and inviting table, you know? You’ll have a great time with it, lots of friends…”

Nate nodded for the door and we left. The husband was pacing back and forth in front of the store enjoying his phone call. “That place is a trip, isn’t it?” Nate said when we were back in the truck.

“Three thousand bucks! And that description!”

“Authentic antique wood farmhouse…” Nate spoke in the voice of the description card. “With all the chicken crap lovingly scraped off by a craftsman who couldn’t afford his own table if he bought it here.” He piloted the truck to the road out of town.

“They can’t just sell it as a table, though,” he said, pensive. “They have to sell something authentic to these people. These people can buy any table they want. A folding table costs thirty bucks. A nice wood table might cost a thousand.” He shook his head. “But they want something to fix their home. Make it real. That’s what people are after.”

We got back to the house in the humming activity just before supper. Two tables were arranged end-to-end. On one our wives had stacked dinner’s dishes; from the other Nate’s sons were clearing that afternoon’s project, a pile of surfboards that needed new coats of wax. Nate had built these tables years before and had never seen any need to age them himself.