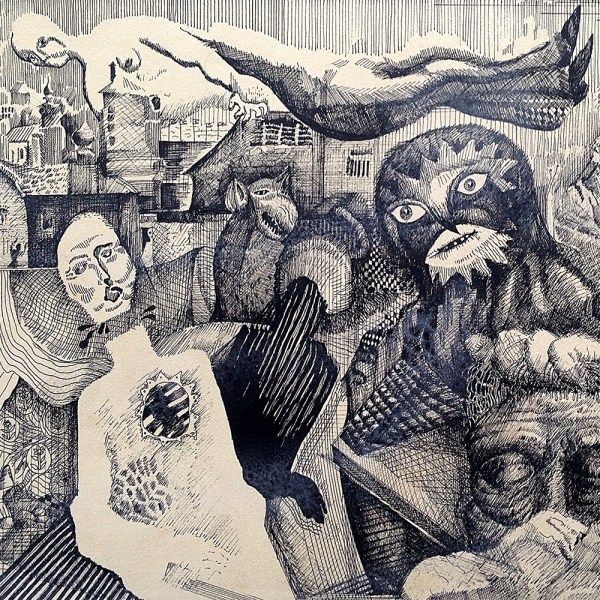

With the recent release of their sixth studio album, Pale Horses, Philadelphia-based band mewithoutYou (henceforth mwY) has once again delivered the musically tight and lyrically dense output their fans have come to expect, including the religious exploration typical of their music. This latest album represents a return to roots for the band, not only musically, but also spiritually. Multiple tracks’ narratives are interspersed with Christian hymns, and the careful listener can hear an acknowledgement of homecoming in the words of the opening track, Pale Horse, when frontman Aaron Weiss sings of the “oil and wine/ I thought I’d left that all behind.” Here, Weiss continues his insistent musical address to God, but who is mwY’s God?

The answer to the question is not so simple as “Jesus Christ,” though Weiss is open about his Christian faith off the stage. Close attention to mwY’s lyrics reveals that the answer lies in the realm of the apophatic or ‘negative’ theological traditions of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam—the three religious traditions with which Weiss works the most and the three religious traditions with which he was raised. The goal of traditional apophatic theology is to probe religious language to highlight its limitations in regard to the God who cannot be contained by human speech and thought. This form of religious speech that questions religious speech serves to prepare the believer for individual contact with God, an encounter that can often be encumbered by theological language.

We can trace this thread throughout the band’s discography, and in what follows I will offer a global interpretation of a number of mwY’s songs that present this apophatic theology. By this global interpretation I don’t mean to suggest that there are no inconsistencies of thought between the albums, or that Weiss’ thought has not developed throughout the band’s career; both of these are true. Nonetheless, there remains a consistent vision with regard to both the language and experience of God that we can discern in Weiss’ lyrics, beginning in earnest with the band’s sophomore album, Catch For Us the Foxes.

Recurrent in this album is the contrast between the revelatory functions of silence and the distracting effect of music and words. In “Leaf,” Weiss bemoans the cleverness of his verbal response to the suffering in the human condition:

“However much you talk…however well you talk…/You make a certain sense, but still only stupid talk /However much I strut around…however loud I sing/ the Shining One inside me won’t say anything.”

This call to silence is repeated in, “The Soviet,” where Weiss pleads for musicians to “turn [their] ears to silence/ for they [the little foxes] only come out when it’s quiet.” The little foxes in this album, drawn from Song of Songs (2:15), signify the sins defacing the vineyard of our lives. In the face of suffering and sin, the human instinct to speak, to make noise, can stand in the way of self-knowledge and contact with the silent Other at the heart of all our striving. There is, of course, an irony to the band using words and music to request that words stop, and the album itself reflects that awareness of this in “Four Word Letter (Pt. Two),” when Weiss promises to “curb all our never-ending, clever complaining,” for “who’s ever heard of a singer criticized by his song?”

This skepticism of talk extends in other mwY songs explicitly towards religious discourse. In “Every Thought a Thought of You,” the opener to their fourth album It’s All Crazy! It’s All False! It’s All a Dream! It’s Alright, Weiss confidently sings, “No need for books when we’re with You.” The reference to holy scriptures (of any faith) is plain, but this statement should not be understood as a blanket call to do away with religious texts; indeed, the incessant biblical allusions that pepper the album make that reading difficult to sustain. Nevertheless, these texts’ ability to accomplish what some religious believers desire from them is directly challenged. In the song “My Exit, Unfair” from Foxes, Weiss sings that he “said water expecting the word/ to satisfy my thirst/ Talking all about the second and third/ when I haven’t understood the first.” This time the contrast is between talking and understanding; there exists an insufficiency in words—however religiously charged they may be—to deliver their promised presences. The religious centrality of water in Christianity is well known, of course, and when we consider that Christ refers to himself as the “living Water” (John 4; John 7), we can appreciate the depth of Weiss’ critique of remaining at the level of tidy religious talk when dealing with the depths of human desire (thirst).

This problem of religious language intensifies in “Fox’s Dream of the Log Flume,” the centerpiece track of the band’s 2012 Ten Stories. Weiss opens the song with cries of the confusion of language: “Provisionally ‘I,’ practically alive/ mistook signs for signified.” The theme is picked up later in the song with an extended metaphor of words as arrows shot out into the world. The story’s narrator sings “midnight archer songs” with “broken bows,” proclaiming “our aimless arrow words don’t mean a thing/ so by now I think it’s pretty obvious that there’s no God/ and there’s definitely a God!” Listening to the song, you experience a jolt of confusion and upended expectation when Weiss apparently confesses to a loss of faith, only to have that understanding immediately reversed by Weiss’ equally insistent claim that there’s “definitely a God.” Here Weiss pushes his listeners to recognize that to speak of God’s existence is a complicated affair, involving negation and affirmation, as well as development over the course of a lifetime. As he sings in the third track of Pale Horses, “D-Minor,” “This is not the first time God has died/…this is not the first time capitalized three-letter-sound has died.” “God” will, in the course of a believer’s life, repeatedly “die,” and this is exemplified by Weiss’ reduction of the idea of God to its bare conceptuality in the meager signification of its spelling and sound.

Belief in God, then, paradoxically involves a certain suspension of belief in God, and suspension of beliefs more broadly is something mwY’s music asks of its listeners for the sake of a deeper contemplation of the mystery to which their lyrics point. They ask their fans not to mistake a sign for the signified. Wrapped up in this suspension of beliefs is a suspension of the self-conception that develops around those beliefs. The dissolution of the self and the dissolution of belief go hand-in-hand, as we can see from a progression of three songs in the band’s third album, Brother, Sister.

Three songs about spiders split the album into thirds. The first, “Yellow Spider,” ends with the lines “Yellow spider, yellow leaf/ Confirms my deepest held belief,” which is then paralleled by “Orange Spider’s” identical ending. However, the third spider song, “Brownish Spider,” goes in a quite different direction: “Brownish spider, brownish leaf/ confirms my deepest held belief…/ no more spider, no more leaf/ no more me, no more belief.” This final line illuminates the development throughout the three songs: From clear yellow, to darker orange, to a muted brown whose edges appear hazy: “brownish” spider. Paralleling the dissolution of the self and belief, then, is a new experience of the world itself.

What might this dissolution of world, self, and belief amount to? Sheer negation or deconstruction? Not so, and the climactic track of It’s All Crazy, “The King Beetle on a Coconut Estate,” shows why. One of the band’s most beloved and brilliant songs, “The King Beetle” presents the clearest picture of the apophatic theology in mwY’s music. Weiss sings the tale of a colony of beetles who regularly wonder in amazement at the fire burned on their estate every year, the “Great Mystery,” as the beetles call it. The Beetle King offers generous rewards for any citizen who can carry back the Great Mystery to the King, and a professor and an army lieutenant volunteer for the task. Both fail; the former due to presumption that his knowledge qualified him for contact with the fire, and the latter because of the delusion that his strength could prepare him to face the great unknown. The King’s wrath toward the lieutenant appears in one of the band’s most dramatic lines: “The Beetle King slammed down his fist,/ ‘Your flowery description’s no better than his/ We sent for the Great Light and you bring us this./ We didn’t ask what it seems like—/ we asked what it is.’” With these words, the Beetle King takes leave of his family and kingdom to fly straight into that Great Light, the “blazing unknown,” as Weiss calls it. The result is a chorus from his subjects, proclaiming, “Our Beloved’s not dead, but His Highness instead/ has been utterly changed into fire.” The chorus continues its chant, “Why not be utterly changed into fire?” until the final, hushed note of the song.

This is the apophatic vision of God championed by the great religious traditions: to strip the self of concepts which hinder the attainment of mystical union with the One whose very being cannot be touched without the complete loss—or transformation—of self. The chorus’ final cry comes from the collection of Sayings of the Desert Fathers, specifically from the counsel of early Christian desert father Abba Joseph to Abba Lot. Lot inquires of Joseph what else he can do to further his monastic vocation, and Abba Joseph responds by raising his hands to heaven, his fingers becoming like ten lamps of fire. He then asks Abba Lot the very question Weiss poses to his listeners at the end of “The King Beetle.” Seen in this light, the apophatic extremism of mwY is a necessary purgation before encountering the greater mystery of God.

One final look at the lyrics of a song from Foxes, this time from the closing track, “Son of a Widow,” will paint a picture of the process and results of such a mystical union. The song begins with Weiss plaintively singing, “I’ll ring your doorbell/ until you let me in./ I can no longer tell/ where You end and I begin.” The main guitar begins its slide downward just as Weiss finishes the word ‘doorbell,’ coming in at such a similar pitch that the listener can easily mistake the guitar for a continuation of Weiss’ voice. The same effect occurs again in the next line, but this time the guitar comes in as Weiss sings “tell,” creating the same continuing effect, but also effecting a union between voice and guitar which parallels the union of human and divine Weiss sings of.

This union is accomplished through incessant supplication (“ring your doorbell until you let me in”), an allusion to Jesus’ parable of the persistent widow and the unjust judge in Luke 18 (which itself connects with the title of the song). Like a lone grape on a vine, longing for the company of the other grapes that have been already plucked, Weiss suggests this union can only be accomplished by being pressed into wine. Here the band plays with Jesus’ statement in John 15 that he is the “true Vine” in which his disciples live. To know the life of that vine, to truly become one with it, the grape must lose itself, its form, and its life: it must be crushed. And that—to let go of ideas, of the world, and selves in order to become one with the One, “Alone to the Alone”—is the apophatic theology of mwY’s music.

In the end, apophatic theology only makes sense within a religious tradition: it is the negative side of what we say about God, a purgative for the positive affirmations of what religious believers trust to be true. MwY’s music pushes listeners to examine again and again what they say and what they believe, not so that they might dispense with faith, but that they might not let their theological language and beliefs solidify into the idols humans relentlessly construct in the place of the true God. “What picture holds us now?” Weiss asks in the Pale Horses song “Red Cow,” and that is the question mwY’s apophatic theology puts to us: what pictures hold us now and keep us from the transformative union hoped for in the heart of genuine faith? Religious belief and apophaticism, affirmation and negation—these go together, for they both, through construction and deconstruction, lead believers to God. This dual movement of the life of faith is best expressed in the final lines of “Four Word Letter, (Pt. Two),” where Weiss shouts to God:

“We have all our beliefs, but we don’t want our beliefs. / God of peace, we want You.”