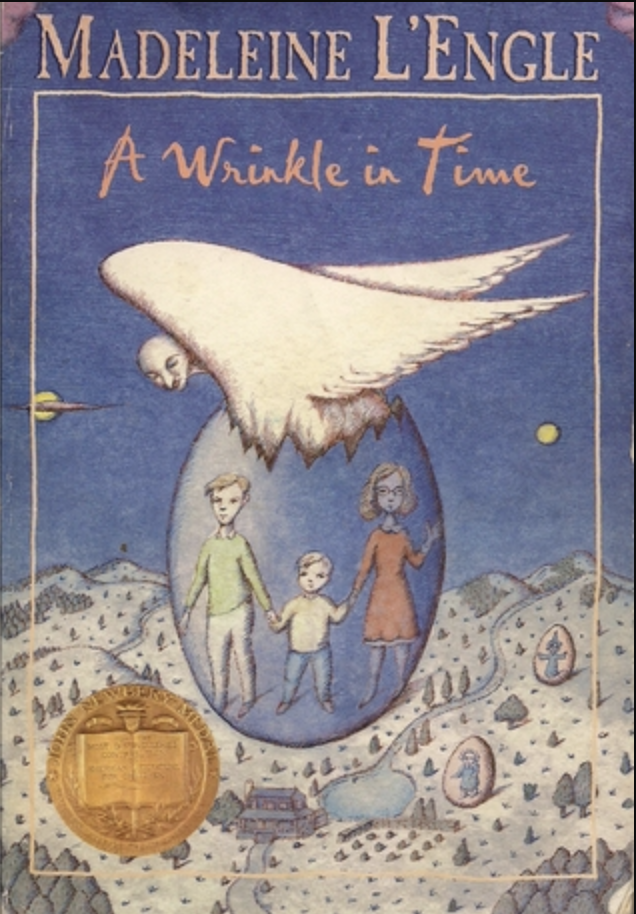

It’s been more than a year since the film adaptation of A Wrinkle In Time came out. Like most movies-based-on-books, the book is, of course, better. The movie doesn’t get everything right, but it is visually stunning, it radiates love, and it nails the quirky, endearing, imperfect heroine of Meg (and, happily, making her much less of a damsel in distress than the novel’s protagonist).

The book and film follow the story of Meg Murray, whose scientist father disappeared somewhere in the universe five years earlier. Meg, her younger brother Charles Wallace, and her friend Calvin are visited by three celestial guides (Mrs. Who, Mrs. Which, and Mrs. Whatsit) who reveal that a dark power is at work and has trapped Meg’s father on a faraway planet. The trio adventure through space and time to try to rescue Mr. Murray.

The film is relatively faithful to the plot of the book, with the addition of some welcome cinematic flourishes.

And then you get to the film’s climax. Within an intricate web of dendrites and neurons representing IT, the source of all darkness on the evil planet Camatzotz, Meg faces her precocious little brother, Charles Wallace, who has been captured by the force of evil. As she desperately fights to save him, she declares:

“And you should love me, because I deserve to be loved.”

This line has been bugging me for months. I can’t get it out of my head.

In many ways, the scene improves on the abrupt, clunky version in Madeleine L’Engle’s novel. (I read the book as an adult, so I’m not nostalgically bound to defend it wholesale.) For instance, in the book IT is a gray, pulsing brain on a dais, making you wonder why Meg doesn’t just throw a rock at the thing and be done with it. The film version, on the other hand, sets a wondrous and intimidating scene that captures the paradoxical enticement of evil.

But the line in question isn’t just a more cinematic update on the original. It actually inverts the powerful Christian message at the heart of L’Engle’s book. In doing so, it becomes a striking example of what filmgoers might lose when creators actively strip originally Christian works of their religious themes.

Despite its sometimes controversial status among evangelicals, A Wrinkle in Time was defined by L’Engle’s faith, and its message is intrinsically Christian. In the book, Meg must go alone to Camazotz, a dark planet and home of IT, to try to save her younger brother. The only help she’s given is the promise that she has something IT doesn’t. There’s no guarantee of her success or safety.

Throughout the novel, Meg has been defined by her weakness. She is clumsy and impulsive. She lacks confidence and relies heavily on others. But despite her lack of heroism, she has been chosen to defeat evil and save her brother, which she does by discovering what she has that IT lacks: the capacity for love.

“I love you,” she says. “Charles Wallace, you are my darling and my dear and the light of my life and the treasure of my heart. I love you. I love you. I love you.” Meg doesn’t have to give this love, and Charles Wallace—whose pride led to his possession by IT and who spends the scene mocking Meg—certainly doesn’t deserve it. But she risks everything to do so, defeating IT in the process.

The scene is grounded by the words of Mrs. Who, who quotes 1 Corinthians to Meg before she leaves to save Charles Wallace, that “God has chosen the weak things of the world to confound the mighty.” Meg, imperfect, unexpected Meg, sacrificially gives love and subverts evil itself.

Unsurprisingly, the movie converts (so to speak) the more overt Christian themes into a vaguely spiritual message of empowerment. For the most part, it is innocuous, with the three guardian angels (who in the book are stars who sacrificed themselves to fight the Dark Thing, “who lost their lives in the winning”) acting more like Eastern mystics and the Happy Medium helping the characters come to a place of “balance” as opposed to simply showing them information in a crystal ball.

Jennifer Lee, the film’s screenwriter, told Uproxx that she wanted to keep L’Engle’s message about “the power of love in the world” while not being beholden to the author’s Christian lens. In her words, “We have progressed as a society and can move onto other elements.” Essentially, for Lee, the message remains the same, but the Christian framework through which L’Engle shared that message is no longer relevant.

In another interview, with IndieWire, Lee repeats this theme: “That [Christianity] was the comfort zone before,” said Lee. “We’re in a different place now, 50 years later.”

I understand where Lee is coming from. Perhaps for the first time, many cultural creators and consumers simply don’t speak the language of Christianity, whether believers or not. We are, as Lee says, in a different place. But while many changes seem innocuous, that earworm line, “And you should love me, because I deserve to be loved,” is very much not. With this line, the movie is not only stripping the outer trappings of religious language, but the very heart of the message. It’s not same story, different lens. It’s an entirely different story altogether.

Meg does deserve love (and she is well-loved by many in the film, including by Charles Wallace), but the power of the climax is in Meg sacrificing herself to give love when it is not deserved, not demanding it when it is. Meg is used in her weakness to overcome an evil outside herself. It’s the power of her self-sacrificing love, as opposed to the strength of a self-empowering, demanding love, that wins the day.

My husband reminded me of Galadriel in Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring, the beautiful elvish ruler who has the chance to take the One Ring from Frodo and wield its absolute power and regain her strength. “All shall love me,” she says, “and despair.” She resists the temptation and instead chooses to diminish so that evil can eventually be defeated (“I pass the test,” she famously says).

It’s not hard to demand love. Such a demand is the territory of dictators.

But to risk your very self to love—that’s the territory of Christ.

Before seeing A Wrinkle In Time, my husband and I read through the novel in a family book club with our niece and nephew. They are religiously unaffiliated, contemporary “nones” raised in secular homes and barely versed in the language of Christianity, if at all. When we watched the movie together, they were not getting the same story with a different lens.

Instead of seeing Meg, imperfect but brave, paradoxically empowered in her weakness, giving love with no guarantee of success, they saw a heroine who uses her empowerment to demand love before she gives it. This picture of love is a mere shadow of the original, tinted by the very darkness L’Engle’s characters seek to fight.

At least they read the book first. As usual, it was better.