“You can ask a lot of questions about the world and your place in it.

You can ask about people’s feelings; you can learn the sky’s the limit.”

—Fred Rogers, “Did You Know?”

I was a late 70s New York City latch key kid: TV dinners were stocked in the freezer for lonely evenings, I got the actual chicken pox, eating bologna and cheese on white bread wasn’t the moral issue it is now. We had scratchy brown-beige sofas and wore unfortunate sweatsuits and played handclap games instead of touchscreen ones. There’s not much more of my childhood that I do remember, though. Like many others, I was a statistic of childhood trauma. Most of my childhood memories are halting, hazy and a bit gloomy, but there were two safe places to which I remember retreating: my Grampa’s freckled arms as we snuggled on his fake-leather recliner and watched Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and under my covers at night with a flashlight and a picture book.

The most precious of my books were ones like Winnie the Pooh, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Frog and Toad; I still have my tattered copies of The Two Admirals and Around the House that Jack Built. The material treasure of my life—I may will to be buried with it—is my well-loved copy of Cinderella by Hilary Knight. I was a self-initiating child, teaching myself to draw by copying pages from my picture books. As time went on, it seemed the stories I gravitated to most were the dark fairy tales such as The Little Match Girl and The Tinder Box. The more difficult and nuanced the hero’s crisis, the sweeter the victory. What these stories offered were existential containment and categorization of experience, which were of immeasurable importance to me in an untethered home life. I believe that is also why I gravitated specifically to Mr. Rogers: his mastery of creating an environment of safe containment. It was within this framework that he encouraged children like me to try new things, to learn about others’ lives, and to be brave in the face of challenge.

Those in my generation remember the calm, reassuring tone of Fred Rogers as we traveled to “The Neighborhood of Make Believe” and watched balloons and crayons being factory-made on “Picture Picture,” but we may not realize the gift he gave to Generations X. I credit him as one of the most profound influences on my work. My career as an illustrator owes a debt directly to Rogers and his validation of the child’s inner life.

Childhood is an expansive time. A child’s imagination is seemingly limitless, and of course that is one of the best things about it. But if the unexpected or unimaginable happens—divorce, abuse, the death of a loved one or even of a pet—the imagination can become a limitless enemy: nightmares, paralyzing fears and distrust of adults can result even from the shadows of these events. We would do well to remember that we do not raise “children.” Instead, we are given stewardship over future adults who must be able to succeed and thrive in a very beautiful, but very flawed, world. Both realities—beauty and pain—need to be acknowledged and prepared for as children grow, within an appropriately expanding worldview.

At a recent coffee date with a friend, we discussed our seven-year-olds’ fears and insecurities. My friend’s daughter deals with separation anxiety, and with powerlessness concerning stories of others’ suffering. Mine struggles with paralyzing irrational fears. I offered to my friend a technique that seemed to be working for us: deep investment in fostering my daughter’s personal prayer life with an infinitely intimate Father. My friend said that she encourages her child to send her fears out into “The Universe.” I wondered later, could that be serving to deepen the insecurity? If we acknowledge this concept of expansiveness, we see that “The Universe” is an awfully big, unknowable place, whether you’re seven or 70.

Booking flights to Europe—does anyone have any SAS Airlines horror stories?The Waldorf educational philosophy pinpoints the end of a “fantasy worldview” right at about age six or seven, which is why, in that model, formal education in didactic subjects like reading are only hinted at until after this “awakening” has taken place. We find this line between “real” and “imagined” to be extremely fuzzy at seven, which explains the monsters in the closet, the bedwetting, the imaginary friend, the fluidity in understanding of time. The last thing that children would seem to need during these formative years would be sending their precious emotional and mental cargo on a spaceship into the Universe. What if the Universe is the Ultimate Closet of Monsters?

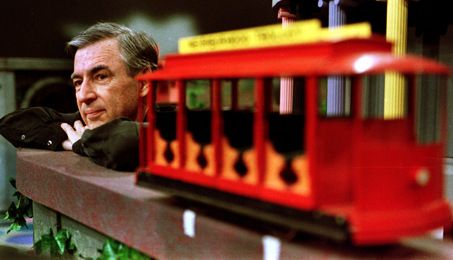

Fred Rogers, however, brings the scale of childhood experience into the confined square footage of the child’s own person.* His small house set is, as he readily tells children, merely his television house. It is a model of the imagination: it has possibilities (Will Purple Panda come to Make-Believe today? What trick does Lady Elaine have up her sleeve?), but also boundaries and routines: Trolley always goes to Make-Believe, never to any place else; Mr. Rogers demarcates the time for imagination by changing out of his “real” coat and shoes into his “playtime” sweater and sneakers. This helps children gently bridge the “real” and “imagined” worlds between which they are in constant flux.

And this is what great books do, too: whether experienced in a lap or under the covers at night, the child has a manageable parcel of real estate in which to park her emotions: See? The world is not as wild as it seems. The Pigeon cannot and will not drive the bus, and Terrible, Horrible, No-Good Very Bad Days do come to an end. Pooh wanders the Hundred-Acre Wood, but always under the omniscience of Christopher Robin. You do not have to wield the sword against the Closet Monster alone, because someone has gone before you, in a book, or a trusted guide, like Mr. Rogers, has told you that you cannot go down the bathtub drain.

Mr. Rogers’ wisdom is just this: children, even children who have endured suffering and challenge, have the innate potential for self-mastery, so necessary for navigating the world. He confirms that you are special, even if your caregivers tell you that you are worthless; your experience and feelings are valid—to your television friend, at least, whether or not your school friends agree; even if the world around you is wild and unpredictable, you have inherent worth, and “people can like you, just the way you are.”

In my own work, I seek to validate the dignity of the emotional life of the child, to provide imaginative possibilities, but never with cheap tricks, manipulative marketing or inescapable despair. It is this scaling down the wild world of which Rogers was such a master, and which is my own guiding principle. I, too, seek to build the mystical Bifrost bridge between “reality” and “imagination” for these future, brave adults who have been entrusted to our care, as parents and as artists.

* Levi Pinfold, in his new and superlative book, The Black Dog, portrays this “shrinking down” of the huge and unknowable into an animal that shrinks as it goes only where the child can fit.

This piece was originally published in April 2013.