“To be brave, knowing beforehand that you’ll be defeated, and to go out and fight: that’s literature.” —Roberto Bolaño

Some years ago, while flipping through a British literary magazine, I did a double take at a visage that looked too much like my father’s. Have you ever lost someone whose image is so ingrained in your own mind that Mnemosyne, regardless of will and desire, is powerless to recall past time satisfyingly (being too near, that is, to ever gain the distance reflective memory requires), causing a kind of delirious self-doubt of self-and-other identity? Who were they? Who am I?

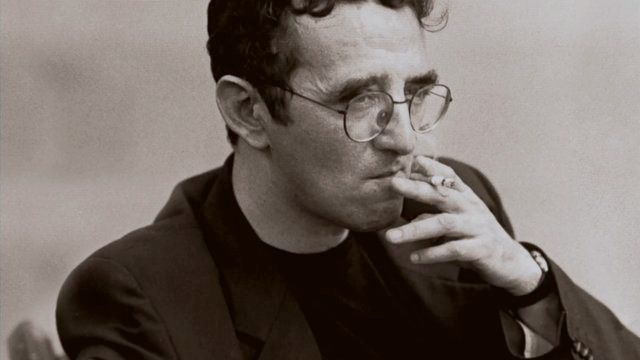

What I find happens in very rare moments is that a stranger, like a cosmic mirror or benign familial Platonic form, brings some obscure mannerism—glance of eye, facial contour or contortion, or, one could even say, spirit—of the lost one to the present and one simultaneously feels joy in the fragments of presence, sorrow in their absence (the phenomena, sadly, being only ever partial disclosures). Something like this happened as I flipped back to the photo of a worn and sick man in that literary magazine: it was a photograph of the great Latin American writer, Roberto Bolaño, with a cigarette wedged between thought and an index and middle finger, who seemed, at least in the first glimpse of the eye, to be my father.

The immediate intimacy the photo roused led me not initially to his fiction but to his interviews, which was probably a mistake: his thoughts, too, were strangely much like my father’s. Here are a couple excerpts from my favorite Bolaño interview given for Playboy Mexico with Monica Maristain:

MM: What is your motherland?

RB: I regret having to give a pretentious response. My children, Lautaro and Alexandra, are my only motherland. And perhaps, in the background, certain moments, certain streets, certain faces or scenes or books that are inside me and that some day I will forget—that is the best one can do for a motherland.

And:

MM: Whom would you like to encounter in the hereafter?

RB: I don’t believe in the hereafter. Were it to exist, I’d be surprised. I’d enroll immediately in some course Pascal would be teaching.

Personally, I have a difficult time not admiring a writer who, despite his atheism, had a great love for the luminescent genius of mathematician and Christian philosopher Blaise Pascal, placing the Pensées in his list of all-time favorite works. Take, for instance, this Pascal epigram from Bolaño’s Antwerp, which if ever there was a nutshell to contain the ambient feel of Bolaño’s works, this would be it:

“When I consider the brief span of my life absorbed into the eternity which precedes and will succeed it—memoria hospitis unius diei praetereuntis (remembrance of a guest who tarried but a day)—the small space I occupy and which I see swallowed up in the infinite immensity of spaces of which I know nothing and which know nothing of me, I take fright and am amazed to see myself here rather than there: there is no reason for me to be here rather than there, now rather than then. Who put me here? By whose command and act were this place and time allotted to me?

“Who put me here? By whose command and act were this place and time allotted to me?” Is this not the question an author’s creations pose back to their author? Is this not the very definition of great fiction: a writer being rewritten by those he writes into existence? A great writer erases the commonly accepted contradiction between reality and fiction, and suspends readers above the abyss of their own consciousness, both individual and collective—she disorientates to re-orientate anew. Reality is fiction being written by an other both intimately ourselves and not. That is, reality is manifested not simply as an objective representation of an external fact, nor is it merely a subjective web casting itself over an impenetrable external world; rather reality arises when subjective awareness touches the world of experience and transforms it into the reality of fiction. Fiction is the dithyramb of reality in our consciousness, it happens both passively to us and is simultaneously created by us. “Metaphors,” a character from his book 2666 says, “are our way of losing ourselves in semblances or treading water in a sea of seeming. In that sense a metaphor is like a life jacket.”

Bolaño’s characters are swallowed up in Pascal’s infinite spaces, both frightened and filled with wonder, searching to find the rhyme or reason they happen to be in this place rather than that place, learning to accept the chaos and pain from which they are conceived. Morini, in a Pascalian flourish from 2666:

“The pain, or the memory of pain, that here was literally sucked away by something nameless until only a void was left. The knowledge that this question was possible: pain that finally turns into emptiness. The knowledge that the same equation applied to everything, more or less.

Life, and the pain that weaves it: but the remembrance of a guest who tarried but a day. O fortuna! Her malfeasant respect for no one, her chaotic devotion to time and chance, convulsing misfortune upon us all, if not now and always, then, well, now and always. (The event of pain has a viral effect upon the past and future, a way of making it seem as if one has, and always will be, as Emily Dickinson said, in pain).

MM: What makes your jaw hurt laughing?

RB: The misfortunes of myself and others.

MM: What things make you cry?

RB: The same: the misfortunes of myself and others.

Roberto Bolaño, most known for his two masterpieces, The Savage Detectives and 2666, received news at the age of 38 that he had an immune disorder that would quickly damage his liver beyond repair. He died on July 15, 2003, at the age of fifty, with his name in the two-spot for a liver transplant.

The last interview Bolaño ever gave was the one mentioned above in Playboy of July 2003 with Monica Maristain. Over a brief span of time, Maristain had struck up a friendship with Bolaño through correspondence and has recently published Bolaño: A Biography in Conversations, an interweaving of biographical narrative and numerous interviews with those who knew Bolaño in some fashion or another. One of the virtues of the book is that it very easily could have spawned hagiography, but it is more often tempered by interviews with those quite ambivalent about Bolaño, and even those who clearly loved Bolaño seem utterly honest with their memories and judgments of him. The result is a unique, mosaic biography of Bolaño: a man of contradictions, both farouche and loving.

One thing about Bolaño to which nearly everyone attested was his desire to push the novel into unprecedented directions. In the aftermath of his fame it’s easy to forget the pains that accompany anyone striving to do something great. They are generally laughed at and ridiculed for attempting something not easily fitted into the criteria of establishment critics. Whenever one breaks molds, Bolanõ noted in Playboy, one often breaks power structures as well:

“Those who have power—even for a short time—know nothing about literature; they are solely interested in power. I can be a clown to my readers, if I damn well please, but never to the powerful. It sounds a bit melodramatic. It sounds like the statement of an honest whore. But in short, that’s how it is.

Bolaño was willing to risk being a “wild writer” (too much energy and too many allusions, “all at constant peak,” as one critic said) if it meant he didn’t have to play “scribbler’s” games. “Scribblers,” as Felipe Rios Baeza, a professor at the Universidad de Puebla, describes:

“…any reader with a passing knowledge of Roberto Bolaño’s work can see a fundamental aspect of it: his great ethical and aesthetic sense of the office of writing. Ethical because on several occasions he said that any contact with political and economic power makes an apprentice writer a courtesan. Aesthetic, because he argued that legibility—the books you take to the beach, books that are easy to understand and have no critical or artistic depth—was something that helped to finance publishers but offered little critical meaning to readers…In summary, readability and prostitution produce hacks, simple receptacles for conventional techniques and subjects with which publishers attract mass readerships …[A] scribbler is someone who doesn’t take aesthetic risks, they repeat well-worn tropes… (Bolaño: A Biography in Conversations)

Such a comment may cause many to condemn Bolaño as an elitist. And here is the great paradox of our age: writers like Bolaño who don’t occupy the higher economic echelons of the culturati are generally possessed with—out of a certain kind of necessity—a stubborn and rigorous originality that is confused with elitism. (Historically, elitists have always expressed suspicion of genius arising from the lower, less formally educated classes. Take the suspicion of Shakespeare, as a general example.) Bolaño, though not deadbeat poor, certainly wasn’t afforded anything resembling the luxury of bourgeois social connections and capital; he simply wasn’t a member of the writerly class for whom success was a guarantee for the mere negative quality of being a not-bad writer. (Walk into most bookstores and you’ll find that many of the books published are by writers who are merely not bad. Their success is due to the elite social and economic class they happen to belong to.) Bolaño had to be great, there was no other way to survive as a writer. As a natural consequence Bolaño was laughed at and mocked for trying to be original. The elite didn’t understand him; he was too strange and not immediately categorizable. Adam Kirsch, describing Bolaño’s 2666, touches nicely upon this quality of Bolaño’s work:

“According to Proust, one proof that we are reading a major new writer is that his writing immediately strikes us as ugly. Only minor writers write beautifully, since they simply reflect back to us our preconceived notion of what beauty is; we have no problem understanding what they are up to, since we have seen it many times before. When a writer is truly original, his failure to be conventionally beautiful makes us see him, initially, as shapeless, awkward, or perverse. Only once we have learned how to read him do we realize that this ugliness is really a new, totally unexpected kind of beauty and that what seemed wrong in his writing is exactly what makes him great.

One inescapable and admirable fact revealed in Maristain’s book is Bolaño’s unequivocal love for children. For all the blood, sex, sweat, wickedness and violence redolent in Bolaño’s work, there is one deadly sin he refused to commit: killing off children.”The only thing that Roberto ever wanted to know about an unpublished book,” one friend says, “was whether a child died in it or not. He used to say that a writer should never kill a child in their book.” I credit this characteristic to some adamantine tenderness and love at the very heart of Bolaño, a quality that underlies everything in his work. Everything else is an accident (in the philosophical sense of not being its essence).

A central characteristic of Bolaño’s wisdom is to know the right people to chafe and the right people to love. Many great authors screw this up: they piss off those they ought to love and love those they ought to piss off. How many writers spent or spend their entire lives neglecting their children to gain the wily fleeting accolades of critics? As a father with two sons, and a son of a father who drank himself to death at a cruel 46 years, Bolaño sums up my fatherly soul:

“[O]ne could talk for hours about the relationship between a father and a son. The only clear thing is that a father has to be willing to be spat upon by his son as many times as the son wishes to do it. Even still the father will not have paid a tenth of what he owes because the son never asked to be born. If you brought him into this world, the least you can do is put up with whatever insult he wants to offer.

Bolaño, along with his fictional world, knew of only one great truth: Love conquers a multitude of sins. And it sufficed for his greatness.

MM: Have you ever believed you were going crazy?

RB: Of course, but I was always saved by my sense of humor. I’d tell myself stories that made me crazy with laughter. Or I’d remember situations that made me roll on the ground laughing.

MM: Madness, death and love. Which of these three things have you had more of in your life?

RB: I hope with all of my heart that it was love. (Playboy)

Additional Links:

http://www.mhpbooks.com/books/bolano/

http://www.mhpbooks.com/books/roberto-bolao-the-last-interview/

Visit the site Wednesday for Layne Hilyer’s reflection’s on the works of Roberto Bolaño as well.