January 12, 2015 was a joyous day for Sufjan Stevens fans. Asthmatic Kitty Records announced the March release of Carrie & Lowell, a new album that according to the AK website, is “ a 44 minute meditation of mortality, memory, and faith.” If the album’s trailer is any indication, Stevens will return to hushed folk form. Named after Stevens’ mother and stepfather, the new album promises contemplative respite from the: “psychic blitz of breaking news, social outrage, and millions of images and voices shrieking” that “does not cease until late at night when the last glowing screen fades to black.”

This forthcoming album will undoubtedly focus on relationships: between God and humanity, between lover and beloved, between artist and art, between reader and text, between self and community. These timeless themes are the stuff of Sufjan’s most well received offerings—Seven Swans, Michigan, and Illinoise.

As we eagerly await the next Sufjan album, this seems to be a good time to revisit his contextually perplexing last album, 2010’s The Age of Adz, as well as the tour attached to it. In fact, the disparaging descriptions of our “noisy age” from the Asthmatic Kitty website sound somewhat familiar to anyone who attended the Age of Adz tour; the “psychic blitz” and “millions of images and voices shrieking” were par for the course. Was this tour just an odd, experimental blip? Or is it an important part of a larger narrative that Stevens is crafting about the nature of relationships, some nourishing, some destructive? All of Stevens’ work seems to include autobiographical wrestling with themes of relationality—and The Age of Adz is, by far, the most overtly autobiographical.

The Age of Adz shocked more than a few fans because of the artist’s unexpected transition from folk flourishes and biblical allusions to the use of both auto-tune and the “f word.” The album’s glossy electronic energy was also showcased during each performance as Stevens and company introduced the new material with the catchy tune “Too Much,” accompanied by a frenetic video projected on a large screen behind them. The video jerkily skipped frames and Stevens, his brother, Marzuki, and a female dancer were all entangled in brightly colored chords, donning eighties work out wear, pulling on and off masks and aluminum foil. The extreme, colorful, filled with chaotic video close-ups overpowered the actual band playing on stage, and this was initially invigorating. The main star of the video was, of course, Sufjan himself; five minutes into this self-indulgent video, the glitz wore off, and what was once seductive and exciting became grotesque in its (intended, self-critical) comic narcissism. The Age of Adz concert performances and album, duel avant-garde explorations of the psyche, navigated the murky relational themes of self-indulgence, self-delusion, and narcissism mistaken for love.

The intertwined categories of what Jewish philosopher Martin Buber calls “I-Thou” and “I-It” relationships provide a helpful framework for attempting to read the abstract, spectacular, yet intimate story of Stevens’ album and stage show.

Both Stevens’ creative chaos and Buber’s mystical reflections explore the ability of the human psyche to objectify, and even project delusions on those we supposedly love.

According to Buber, an “I-It” relationship is one in which we relate to another person based solely on what he can do for us, for how she makes us feel. An “I-Thou” relationship is one in which we appreciate, listen to, and live in a perpetual state of wonder as we encounter another person’s “otherness,” sensing the other’s inherent value and not attempting to mine their “use” value. Paradoxically, Buber argues in I and Thou that only through “my relation to the Thou” can “I become I” (11). Only through allowing space and respect for another’s being can we become more ourselves, grounded in the reality of relationship.

We see embodied examples of perpetual relational spasms—from the objectification of the other, to the act of truly cherishing the other—as Stevens’ album opens with the delicate acoustic love song “Futile Devices,” a piece that follows directly in the folk footsteps of much of Stevens’ earlier work (particularly Seven Swans and Michigan). This is a song about a nostalgic lover, longing to reunite with the object of his affection because “you are the life I needed all along.” Stevens repeatedly sings, “I do love you” but then realizes it is useless to say this because words are “futile devices.” The conventional calm of the album’s first song is short lived, and what follows is a jagged, chaotic, frenzied and beautiful mess that reflects the mind of the lover as he navigates the relationship.

Although the increasingly cryptic lyrics and frenzied electronica of the rest of the album are an aesthetic jolt after the first song, they are thematically consistent. The deceiving calm of a when lover makes another in his own image, the “life I needed all along,” is an act of both objectification and narcissism. In the next song (which happens to be the soundtrack for the garish video described above) Stevens sings, “There’s too much riding on that.” Yes, the yearning lover is banking his devotion, his identity, and ultimately, his own pleasure and sense of well being, on another, consuming her in the process.

Buber claims that “all real living is meeting”, yet the cacophony of the rest of Stevens’ album reflects the reality that the central relationship is not a “meeting” but a violent clash. When one projects himself onto another to serve his own purposes, the connection is violent, not harmonious—even if the initial euphoric, “romantic,” calm briefly disguises it.

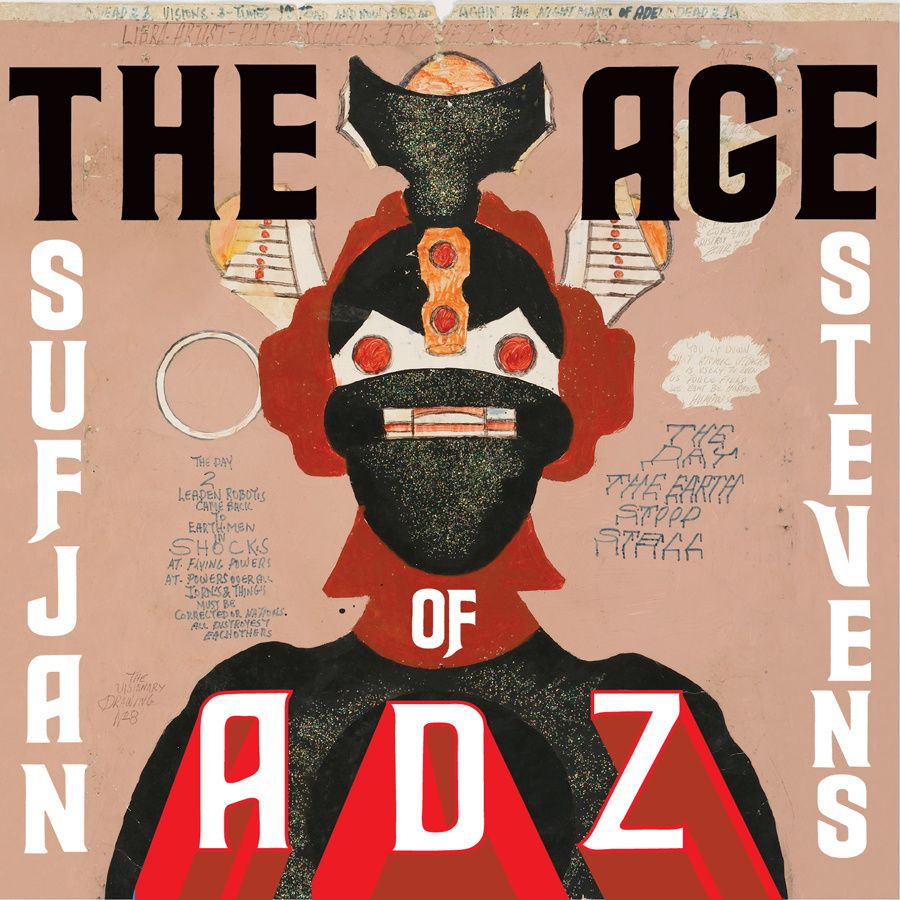

As the album continues, Stevens pulls in another narrative strand from the perspective of Louisiana folk artist, Royal Robertson. Robertson’s original art provided the often ominous background art for Stevens’ performances, as well as the album’s cover. During each of the Age of Adz performances, Stevens spoke for around 10 minutes about Robertson’s life narrative and art because this life and vision of a fellow artist had become, “a very comfortable place to live and reside in.” Robertson had, Stevens explains, the “gift of prophecy, out of body experiences, visions from God and angels, spaceships, aliens.” Ultimately, Robertson’s “gifts” were responsible for, as Stevens said, “ushering him to insanity;” the gifted artist eventually became violent, and the episodes of prophetic vision were diagnosed as schizophrenia. Royal’s life became one of isolation and poverty, populated almost entirely by delusions. His relationships became strong-willed collisions rather than spaces for reflexive participation and, eventually, he was abandoned by all friends and family.

Clearly Royal’s tragic story can also be linked back to the central relational entanglement of Stevens’ album. Just as Robertson had lost any distinction between the objective world and his internal reality, Stevens’ love story asks questions about what we think is really “real” in a relationship. What is a personal projection and what is truly the “other”? How do we prevent objectifying the “other” through these projections? And how do we prevent ourselves from slipping into the quicksand of complete solipsism?

Directly after speaking about Robertson’s story on stage, Stevens then performed “Get Real, Get Right” which he deemed “my reality check song.” The song’s images mostly belong to Robertson’s artistic world: spaceships, rings of fire, prophets, etc. But a powerful, poignant bridge leads to the song’s chorus, layering instruments to provide a rich, almost painfully joyous sound that perhaps points to some reality beyond the delusions: “I know I’ve caused you trouble/ I know I’ve caused you pain/ But I must do the right thing/ I must do myself a favor and get real/ Get right with the Lord.” This bridge breaks from the delusional internal world, perhaps suggesting that only the ultimate Reality, God, can help us to distinguish between the fantasy of our own projections and the real world outside of ourselves. Only in a moment of confession, a pleading to know where he ends and an eternal reality begins, does the speaker begin to “Get Real.”

But as the album progresses, the exploration of the nightmare of self-consumption continues. Stevens tells us in one song that “I want it all for myself,” then perhaps examines the devastating effects of this greed in “I Want to be Well:” “Did I go at it wrong?/ Did I go intentionally to destroy me?/ …I could not be at rest, I could not be at peace…”

Although this song expresses an overt desire to escape the sicknesses of body, mind, and soul, Stevens also seems to ask if this wellness, this understanding of the distinction between self-projected fantasy and any sort of real reality is itself an impossibility for the human soul? Perhaps we should just abandon a quest for “health” and turn to the comfort of consumption as we “eat and drink, for tomorrow we die” (1 Corinthians 15:32)?

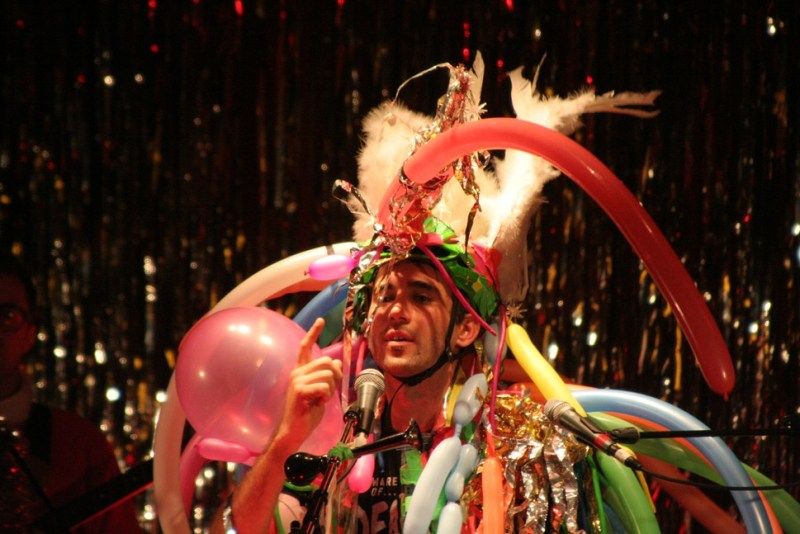

Age of Adz’s final song, the 25 minute long “Impossible Soul,” is an artfully convoluted mixture of denial, despair, and then ultimately, confession. In his concert performances, Stevens and his band played space age dress up while a model of one of Robertson’s spaceships descended onto the stage. As the lights went up and balloons descended across the concert hall, the audience jumped to its feet, rejoicing in the fun of make believe (or happy delusion?). As Stevens used auto-tune to alter his voice while singing to his lover, the words of the song became their most dishonest: “Girl, we could be so much together.” This use of auto-tune, an inhuman, mechanized distortion, highlighted the fact that as the lover objectifies the beloved, moving more deeply into an “I-It” relationship, he becomes less human.

But this picture of depthless inhumanity was entertaining, funny, and even more of an invitation to join the party—a laughing descent into the void. Discussing “Impossible Soul” in an interview with Drowned in Sound, Stevens explains the “joyful” tragedy of the song: “It’s like a Woody Allen film, you know, where there’s the slapstick on the surface that everyone can appreciate, but then, deeper, there’s all these original details. Maybe at the heart of a good Woody Allen film there’s some kind of universal tragedy of humanity that he’s speaking about; a much bigger thing.”

What is this “universal tragedy”? Is it the death of relationship due to a desperate clinging to counterfeit pictures of the other, pictures that are little more than self-indulgent projections? The song and album end with a complete break from glitz and glam, a reversion back to the gentle acoustic sounds of the opening track. As the auto-tune is turned off and we hear the truly organic sound of a very hushed, very humble, very human voice, we are startled by the confession:

I never meant to cause you pain

My burden is the weight of a feather

I never meant to lead you on

I only meant to please me, however…

I’m nothing but a selfish man

I’m nothing but a privileged peddler

And did you think I’d stay the night?

And did you think I’d love you forever?

And then you tell me, boy, we can do much more

I got to tell you, girl, I want nothing less

Girl, I want nothing less

Girl, I want nothing less than pleasure

Girl, I want nothing less than pleasure

Does the raw honesty of this confession signify a movement from an “I-It” relationship to an “I-Thou” relationship? The lush, intimate sound of an all too human voice could indicate a re-humanization of the lover after his acts of dehumanizing self-indulgence. Can this moment of self-awareness, this attempt to “Get Real” also lead to the possibility that the relationship will “Get Right”?

Maybe.

But maybe not. The warm sounds of the album’s final few moments also ominously echo the deceptively beautiful words and music from the opening track, perhaps even implying an ongoing cycle rather than an actual transformation. Maybe these final words of confession are simply the same sort of hollow, “futile devices” that began this dishonest relationship.

We do not know if we can trust the lover’s supposed epiphany at the end of the album; but then again, he probably can’t either. He is a mystery to himself, a tangled knot of contradictions and falsehoods. Blaise Pascal’s explanation of fickle human nature summarizes the arc of Age of Adz: “What a chimera, then, is man! What a novelty! What a monster, what a chaos, what a contradiction, what a prodigy!…depositary of truth, a sink of uncertainty and error; the pride and refuse of the universe!”

Stevens’ album is a poignant, painfully honest depiction of the darker “symptoms” of the human condition: self-deception, inconsistency, and narcissism. If we listen closely and honestly, we may come to realize that we are left with a revealing portrait of ourselves—and with Blaise Pascal’s own desperate, yet hopeful, question: “Who will unravel this tangle?”

In this “noisy”, garish, yet artfully honest installment of the Sufjan Stevens catalogue, we see perhaps the darkest chapter in Stevens’ larger narrative of human relationality. If we listen intentionally and carefully, we will be both seduced and burned in the Age of Adz’s post-relational Wasteland. Will Carrie and Lowell provide a more redemptive picture of human relationships, perhaps a balm to begin healing the self-inflicted wounds of The Age of Adz? We will have to wait until March to see.