Contemporary artists Bruce Herman and Makoto Fujimura have collaborated with composer Chris Theofanidis in a multi-media exhibition called QU4RTETS in response to T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. Premiering at Baylor University (2013), the exhibit traveled to Duke, Yale, Hong Kong, and most recently Cambridge University during Holy Week. Theofanidis’s original score for the quintet, At The Still Point debuted at Carnegie Hall in February 2013, with subsequent performances accompanying the painting installations at the Eliot symposiums. The contemporary musical composition is fitting for the poetic text, evoking unfamiliarity and restlessness in the audience, stylistically echoing the fragments and irresolution from Eliot’s poetic structure. Both Herman and Fujimura agreed that similar tensions exist in their paintings, a kind of visual synesthesia in form and color, meditating on the complexities of Theofanidis’s music and Eliot’s language.

In an art salon colloquium at Duke Divinity School amidst the Engaging Eliot symposium, Bruce Herman expressed the difficulty of rendering the two female figures in his series, repainting each of them many times, continually unsatisfied with the results. Herman voiced the challenge of executing a realistic female form due to the convoluted visual narrative of modern and contemporary art history, in which the (historically male) artist tends to objectify, sexualize, deify, or domesticize women. For Herman, this presents a problematic visual inheritance for the artist to grapple with, which we can see in his two female depictions from QU4RTETS. Herman’s paintings raise the question: What makes the representation of the female image in contemporary art, particularly religious art, so difficult?

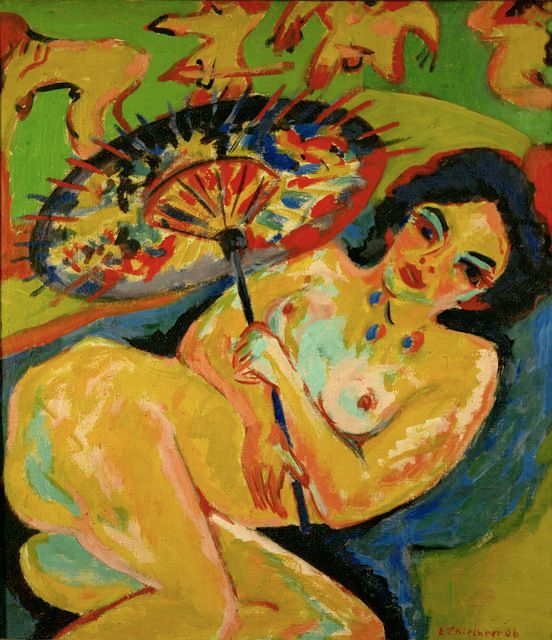

In “Virility and Domination in Early Twentieth Century Painting,” art historian Carol Ducan posits that women from the beginning of modernism onwards are depicted one of two ways.[1] On one end of the spectrum, the virility of the male artist is present in the uninhibited sexual appetite of the artist’s depiction of powerless and sexually subjected woman, often sexual clients before or after the portraiture session, sometimes portrayed in the very room or studio in which they were used. In this mode of representation, the male artist’s productivity is dependant on the woman as his creative muse, where she is reduced to flesh as an obedient animal. We see this approach dominate painting schools from Fauvist and German Expressionism, in works by Vlahminck and Kirchner (Girl Under a Japanese Umbrella, 1909).

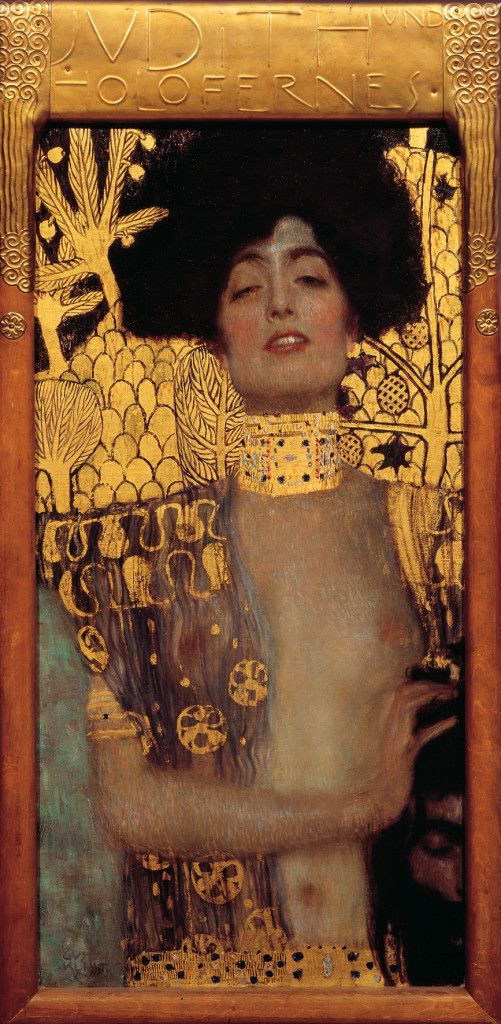

In contrast, the other method of female representation is a type of femme fatale or mythologized goddess, usually a type of Eve, Lilith, Salome, Sphinx or Madonna figure. Employed in works by both Munch and Van Dongen, perhaps Gustav Klimt’s sirens from the Jugendstil fin-de-siècle period in Vienna are the quintessential illustration of this type (Judith, 1901). Klimt’s usage of metals, particularly gold (not unlike Herman’s), is rooted in the tradition of orthodox iconography. While Klimt diverges from the explicit realm of the religious, his gold nevertheless divinizes his women as goddess figures, often associating sexuality with violence and death. The metals connected with these images are “decorative”, an aesthetic decadence acting as a facade concerned with the mere surfaces of things. While Klimt’s depiction of woman is provocative by using beauty as a seductive yet animating force, there is a disturbing undercurrent that does violence to feminine sexuality.

Duncan argues that Picasso attempts to critique both positions in his frightening masterpiece Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (1907) where he:

“brings together both the femme fatale and the primitive; whore and deity; decadent and savage, tempting and repelling; awesome and obscene, threatening and powerless…Picasso presents [his women] as desecrated icons already slashed and torn to bits…Only in ancient art are women as supreme and subhuman as this…They are real bodies, in a real brothel that really is commodified. And you are the commodifier.[2]

Thus, Picasso diagnoses and unmasks the spectrum of female representation in modern painting, implicating the viewer as a participating voyeur in the artist’s schema. His hermeneutic opened up new questions of art criticism in regards to how and which female forms were rendered and why. Race, colonialism, class, power, gender, sexuality and even body weight all became significant factors in conveying and assessing the subject’s humanity to the viewer. This critique, however, carried new responsibilities for the artist by acknowledging the problematic precedence of female portraiture.

Drawing upon T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets as the inspiration for the QU4RTETS project, Herman’s subject matter and thematic representation of women are arguably informed by Eliot’s text. The name of Eliot’s “Dry Salvages” references a location known well to Herman, a cluster of rocky islands off the coast of Glouchester Massachusetts. Herman’s atmospheric familiarity of Eliot’s setting aids his painterly interpretation of Eliot’s poetic symbolism of water, fitting for both seaside landscape and baptismal iconography. Perhaps Eliot also utilized this particular location for the title’s enunciation (“sal-vay-ges”), playing on “salve”, the hail given by Gabriel at Mary’s Annunciation (“Hail, favored one! The Lord is with you!”).[3]

We find Eliot’s explicit referral to Mary in the text of the “Dry Salvages”, providing us with a larger narrative of both Annunciation and Incarnation. For Eliot, Mary is the Stella Maris, the “star of the sea,” the guiding light to voyagers as an intercessor to her Son:

Lady…pray for those who were in ships, and

Ended their voyage on the sand, in the sea’s lips

Or in the dark throat which will not reject them

or wherever cannot reach them the sound of the sea bell’s

Perpetual angelus.[4]

For Dante, the stars were a theological symbol of hope, an ever-present guide for Virgil and Dante in the Divine Comedy. Astronomically, the Stella Maris refer to Polaris, the “North Star”, which seamen used as a navigational axis for transversing the seas. The vespers hymn “Ave Maris Stella” to which Eliot alludes in the “Dry Salvages” illuminates Herman’s QU4RTETS depictions:

Receiving that “Ave” (hail)

From the mouth of Gabriel

Establish us in peace

transforming the name of “Eva.”[5]

This hymn relates to trope from St. Irenaeus of Lyons that Mary’s “yes” to the Annunciation transposes Eve’s “no”, the theological recapitulation of female history. We might consider Eliot’s employment of patristic typology the entry point for discussing Herman’s representation of women in his QU4RTETS series.

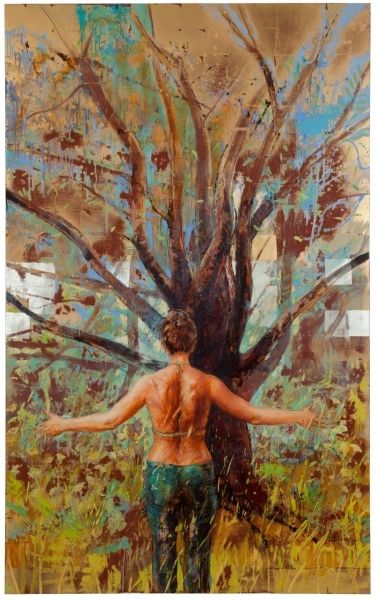

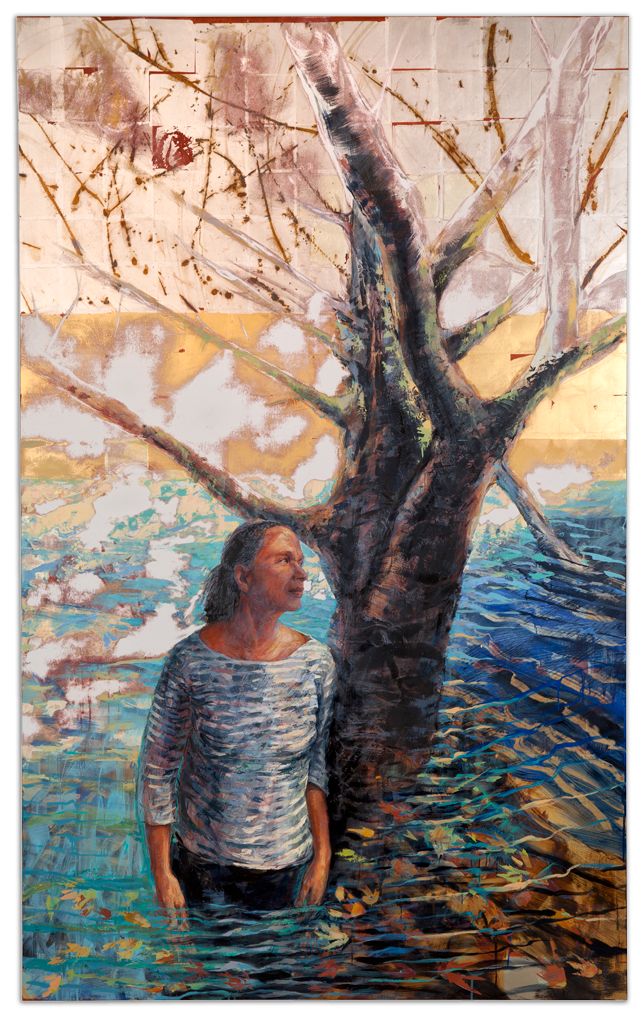

The Marian undercurrents from Eliot’s “Dry Salvages” frame and inform Herman’s two female portraits: one younger, with her back towards us (QU4RTETS No. 2: Summer) and the other middle-aged, in a kind of afternoon reverie (QU4RTETS No. 3: Autumn). Attempting to navigate the modernist typologies of female portraiture, Herman draws upon Eliot’s Marian typologies seeking to humanize his female bodies. In this way, Herman tries to avoid objectification and deification by situating the visual imagination of women within Christian iconography—the Magdalene and the Virgin.

In QU4RTETS No. 2 Summer, Herman gives us a kind of Magdalene figure who wears the scars of suffering in her very body, aligning herself with the tree as a kind of participation in the cross. Glancing at the woman’s back, Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece for the community of lepers and Donatello’s sculpture of Mary Magdalene come to mind, which Herman admits were formative for conceptualizing the young woman’s portrayal. Grünewald’s Christ is contorted with skin lesions and open sores, his immense suffering evident with his outstretched hands in surrender. In a similar manner, Donatello’s Mary Magdalene is gaunt and emaciated, with her skeleton protruding, teeth missing as she attempts to fold her hands in prayer. Herman additionally draws upon Georges Rouault’s prostitutes (Fille), whose grotesque women (or “gutter Venuses” as French Novelist Emile Zola would say) reject objectification from the viewer’s gaze, evoking compassion instead of judgment.

Using a palette knife, Herman builds textural elements with paint to create stigmata-like depictions on her body. This expressive “unfinished” process descends from Willem De Kooning, a formative stylistic influence on Herman, as Herman’s mentor Philip Guston was among the New York Abstract Expressionist school. De Kooning himself had a radical approach in his female depiction of women, especially his haunting Woman series. Looking more like fallen Eves over Paleolithic goddesses, De Kooning critiqued societal mores of women in 1950s advertising through his representations of obtuse bodies with garish faces. Both Willem De Kooning as well as Richard Diebenkorn influence Herman’s color palette employed in these QU4RTETS portraits, particularly the paring of periwinkle and cerillium from Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park series, followed with lilac, celery and chartreuse, sienna and terra cotta, aquamarine and cobalt. Consequently, Herman is not only drawing upon De Kooning and Diebenkorn merely in their employment of color alone, but also in how they are innovating representational portraiture and landscape with the medium of paint itself.

In QU4RTETS No. 3 Autumn, we see a woman in a French-bateau striped shirt wading in the aquamarine pool, fallen leaves surrounding her. The barren tree indicates the presence of Autumn, both literally and figuratively in the woman’s season of life. In this type of portrait, we see a mature woman, perhaps a mother—an allusion to the Blessed Mother. Marian iconography is not unfamiliar to Herman, as Matthew Milliner has also associated the Virgin Mary with QU4RTETS No. 3 Autumn in his exhibition catalog essay. Herman’s earlier Magnificat triptych (2009), Overshadowed, captures the moment of the Incarnation, while the nod to Mary as the “New Eve” informs his Second Adam and Miriam: Virgin Mother. Both his Woman and Virgin Mother series establish a Marian precedence for these portraits, making the female typologies a direct projection of the Magdalene and Marian figures.

Following the earlier paradigm of “Eva” becoming “Maria”, the task of the painter who attempts to portray the female in contemporary art must wrestle with depictions of Eve (like Picasso’s “desecrated icons”), idealized goddesses (Klimt’s Judith) and even the Virgin Mary, Mother of God. Whether we see suffering and brokenness in the Magdalene or perfect humility and obedience from the Virgin, both women have an iconographic history in artistic representation. However, post-modernist painting challenges these tropes because they fail to provide a spectrum for women between the polarizing typologies of the prostitute and the virgin.

Eleanor Heartney argues in Postmodern Heretics: The Catholic Imagination in Contemporary Art that contemporary feminist artists have found the Magdalene and Virgin tropes an oversimplification for the iconography of women. In attempting to deal honestly with female sexuality and human equality, many have found the Virgin Mary to be a problematic ideal for women. For Catholics, she is not only conceived without sin and perpetually a virgin, but she is also uniquely the Mother of God—an event unprecedented or proceeded by any other woman. To offer the Virgin as the anecdote for female objectification is hardly generous nor helpful. She is not the archetype of femininity as achievable by women, but a paragon of divine motherhood—the Queen of Heaven.

Grünewald, Donatello and Rouault offer three artistic depictions of women’s humanity that is worn and broken beyond recognition, suffering in the very surface of their skin. This deeply incarnational approach to rendering the female form indeed resists objectification, but we must ask if Herman’s QU4RTETS align themselves with and draw upon these seminal works of art. To consider them as Eliot’s Stella Maris, Donatello’s Mary Magdalene and Rouault’s Fille, I’m left wanting. The sentimental expression in both women lack a three-dimensional depth with which I can identify. The challenge for Herman to narrate the iconicity of the female face lies in authenticity, having eyes to the past aware of what male artists have failed to do, as well as thoughtful attention to contemporary female artists’ rendition and representation of themselves. Though perhaps graphic and unsettling at times, as in the portraits by Jenny Saville, they are real women in an embodied world that cannot evade representation through abstraction nor spiritualization.

[1] Duncan, Carol (1973) `Virility and Domination in Early Twentieth-Century Painting’, Artforum December.[2] Duncan, Ibid.[3] Luke 1:28[4] Eliot, T. S. Four Quartets. London: Faber, 2000. III:IV[5] “Ave Maris Stella.” Ave Maris Stella. http://www.preces-latinae.org/thesaurus/BVM/AveMarisStella.html 07 Apr. 2015[6] Eliot, Ibid.