After nearly ten years as a New Yorker, and having worked in the entertainment and prestige beauty industries before entering the arts world where I now reside, I have learned that there is no point in trying to predict what will happen to me each day – whom I will meet, where I will end up, or what I will see. A couple weeks ago I met my friend for Vietnamese food in Chinatown, where, over sour vegetable soup and two pots of tea, we talked at length about the intersection of art and social justice. This friend, a sculptor, is deeply devoted to helping humanity’s most needy, and this devotion is born out of an intense closeness with God and healthy sense of mysticism that enables her to see angels where the rest of us might only see mere men.

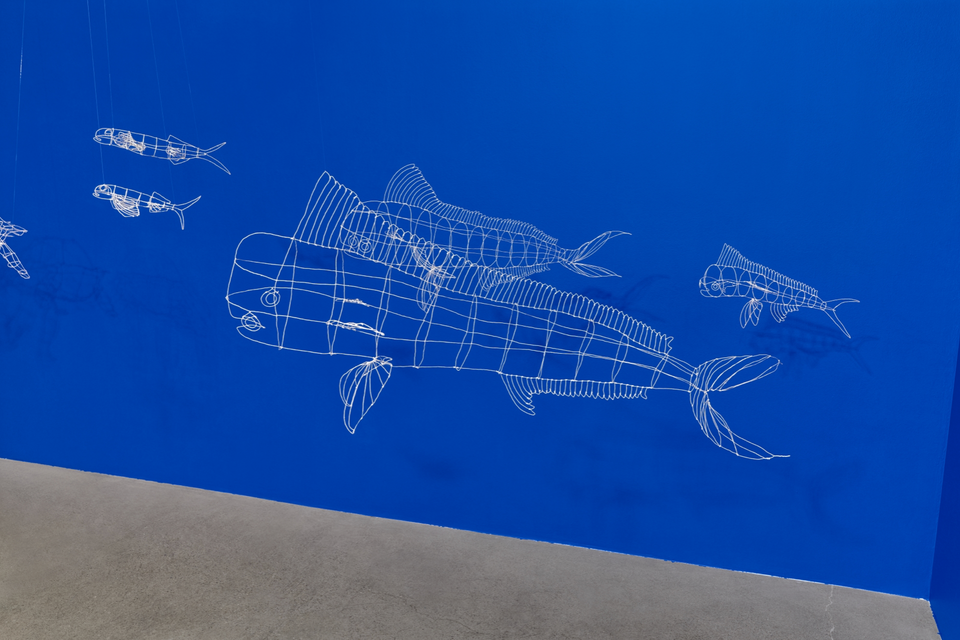

After dinner, we headed to Chelsea to attend the opening reception for Traffik, an exhibition by fashion photographer Norman Jean Roy at MILK Gallery, open to the public November 21 through December 8. MILK, located at 450 W. 15th Street, is considered to be New York City’s most prestigious photography gallery, and Roy is one of the most prominent high fashion photogs, under contract with Conde Nast to shoot exclusively for Vogue, Vanity Fair, Men’s Vogue, Allure, and Glamour.

With a resume like that, it’s no wonder that as we neared the gallery, we felt like we had walked onto the set of Entourage. Entering MILK and passing the hefty team of security guards, we were immediately swept into 6,000 square feet of models, agents, creative directors, managers, editors, and other photographers. The walls were hung with nearly fifty images, approximately four feet by five feet each. They were portraits of Cambodian prostitutes and other victims of the sex trafficking industry. The images were beautifully shot and the small placards posted beside each one gave a brief history of each subject featured. For anyone interested in the plight of victims of sex slavery, it would seem that this was a very important exhibition to attend.

However, the evening left both my friend and me deeply unsettled, because walking into the gallery, we entered what looked and felt, for all intents and purposes, like a house party. Club music was pumping, with a bass boost that reverberated through our ear canals and pulsated through our bones. The several hundred people bumping into one another throughout the huge room were talking so loudly that I could not hear my own words, and, from all appearances, very few of the people present were engaged with the art.

Interestingly, this was my second event dealing with sex trafficking in the past few weeks. On November 6, International Arts Movement hosted a screening of the film Branded, a documentary about the sex slave industry in Phoenix, Arizona. Following the film, I moderated a panel discussion with the filmmaker, Chad De Miguel, and a representative from Food for the Hungry, a non-profit organization committed to rescuing victims of the sex industry. I was surprised at the show when a woman came up to me and shouted through the noise, “You’re from International Arts Movement, right?” Trying to place her face (and failing), she quickly rescued me by explaining that she had attended the Branded screening, and I finally recalled meeting her briefly that night.

She works full time for a non-profit that is devoted to helping put an end to sex trafficking, and we tried to engage in meaningful conversation, but the atmosphere made it virtually impossible. I was yelling at the top of my lungs, and still couldn’t hear myself, or her. We exchanged cards and agreed to meet sometime in the future to discuss how IAM and her organization might partner together.

As I made my way around the outside parameters of the room, reading the placards and studying the artwork, I was increasingly ill at ease with the scene I was smack dab in the center of. As I watched people laughing and mingling and networking and scanning the room for who was there, eager to see and be seen, the paradox before me became increasingly obscene. I felt like I was looking at a room full of sex industry workers surrounded by images of sex industry workers; both the industry represented in the flesh, and the industry represented on film used sex to sell their wares.

At one point I pulled out a pen and began making notes about what I was experiencing. Shortly after I had started writing, a man with shoulder-length blond hair bee-lined for me, a full glass of white wine sloshing around in his hand. I didn’t need to hear his slurred speech to know he was drunk; his red eyes and dopey smile spoke volumes. “What’cha writin’?” he asked in a singsong manner, which was creepy coming from a man who appeared to be approximately fifty years old. I stared down at him and managed to dodge him for a bit, but quickly became the unwitting audience to his editorial of the event. “We can’t look at this from an American perspective, with an American standard,” he blathered. “These girls . . . what else do they have? This is all they have. We shouldn’t judge them. This is all they know. This is their life. They’re not asking to be anything other than what they are.”

I was dumbfounded. Was he serious? I’m afraid he was. I contemplated trying to reason with him, trying to somehow get past the incomprehensible ignorance of one who could stand in front of a picture of a woman with deep scars all over her body and filthy, infected lesions on her feet, who barely earned her living by servicing men sexually, and think this way. But I was not up to shouting, and I knew that nothing I could say would make any difference. As I excused myself and walked away, he said something about the self-righteousness of expecting people in other countries to live up to our American standards. I actually did say something to him about them not being “American” standards, but rather basic humanity standards, but he dismissed me.

With the paradoxical scenario of serious subject matter and a party-like atmosphere, I was very curious about the background of this exhibition. According to the press materials I managed to procure, the project came about when Norman Jean Roy was on assignment for Glamour‘s “Women of the Year” portfolio. Roy was introduced to Somaly Mam, a former Cambodian sex slave who was being honored for her work rescuing women trapped in the sex industry and helping them reintegrate into society. Overwhelmed by her story and haunted by the faces of the women Mam had worked with, Roy decided to spearhead a project that would expose and elevate the grave reality and gross injustice of their experiences.

So last January, Roy returned to Cambodia to photograph the victims, gaining access to brothels with the help of Mam and her organization, AFESIP. He was able to observe and document the harrowing lives of working adolescent and child prostitutes, as well as those who have been rescued and are now in rehab at AFESIP centers. The book that resulted, which was the center of last night’s exhibition, was Traffik, which captures the powerful stories of young women who were beaten, starved, raped and tortured as sex slaves. Several of the women talked about being sold by their mothers and being raped as children as early as age four.

As I watched the professionals in one sex industry mingling and drinking wine while being surrounded by larger than life sized images of professionals in another sex industry, the pungent odor of sick irony filled my nostrils, and I wanted to scream. The very publications that use sex to sell their wares were, I guess, ostensibly mourning for victims, half a world away in a physical sense, yet in a totally different universe in the social sense.

Except they weren’t mourning. Honestly, it would have been a very noble scene if they had been. High-profile fashion and beauty professionals in a prestigious New York gallery, stepping out of their party-hopping and schmoozing for one night to examine the horrors of sex slavery? It would have brought a tear to my eye – seriously.

But, from what I could tell, a relative few people were even looking at the images, let alone showing any sort of deep emotional reaction to it. And while the images are very well shot and are effective in capturing the essence of prostitution in the impoverished developing world, set in the context of loud music and a well-stocked open bar, something just felt icky. One image was particularly disturbing in light of the environment we were in. A young girl was dressed in sexy shiny panties and grown-up jewelry, lifting her shirt and looking at the camera with an almost seductive expression that was totally incomprehensible in light of the fact that she could not have been older than four. She was labeled as a child of a prostitute, but it was not much of a stretch to imagine her entertaining clients herself. At the very least, she had to have observed the business her mother was in. The image might have been simply a snapshot of a little girl playing dress up, except that she was living in a brothel, where, according to the press materials available, men pay more for sex with girls between four and seven years old, believing them to be less likely to carry STD’s. (They are, unfortunately, mistaken in that assumption).

Yet, in the milieu of pulsating club music and a plentiful supply of wine and liquor, I wondered at whether there might be people in the room with pedophiliac tendencies who, rather than being correctly horrified by it, would instead be turned on. The music, which was fine by itself, and the wine, which I appreciate regularly, simply did not belong together with images of four-year-olds dressed in sexy lingerie. For everything there is a season – a time to dance, and a time to mourn. But when people are (figuratively) dancing in the midst of such a painful exhibit, it becomes almost a mockery of the tragedy.

When IAM screened Branded, we were very mindful about the context in which the film was shown. We sold no concessions that evening. No wine, no beer, no popcorn. Our intent was that, from the time people entered the space to the time they left, we would foster an environment of concern and soberness about the issue at hand. We hoped that the film would inform our audience, inspiring them to leave the space and look for ways to engage with the issue of sex trafficking, to help change the destiny of the victims and create the world that ought to be. Indeed, there is a time to dance, and Space 38|39 has seen plenty of playful reverie. But when it’s time to mourn, it’s time to mourn.

Unfortunately, this was not the case at the opening reception for Traffik. The project is important, and I hope people will attend the exhibition, buy the coffee table book (whose proceeds will benefit Somaly Mam’s Foundation) and leave more informed about this blight on humanity. Norman Jean Roy’s work in this project is excellent, and I applaud his use of his talent and opportunity to bring this awful situation to light.

However, I am not hopeful that many people at last week’s reception – people of great means and influence who, if engaged, could make a world of difference – will. People who actually hear a call for action are more likely to respond by doing something about it. Unfortunately, it was hard to hear anything above the roar of the electronica that blared through MILK that night.