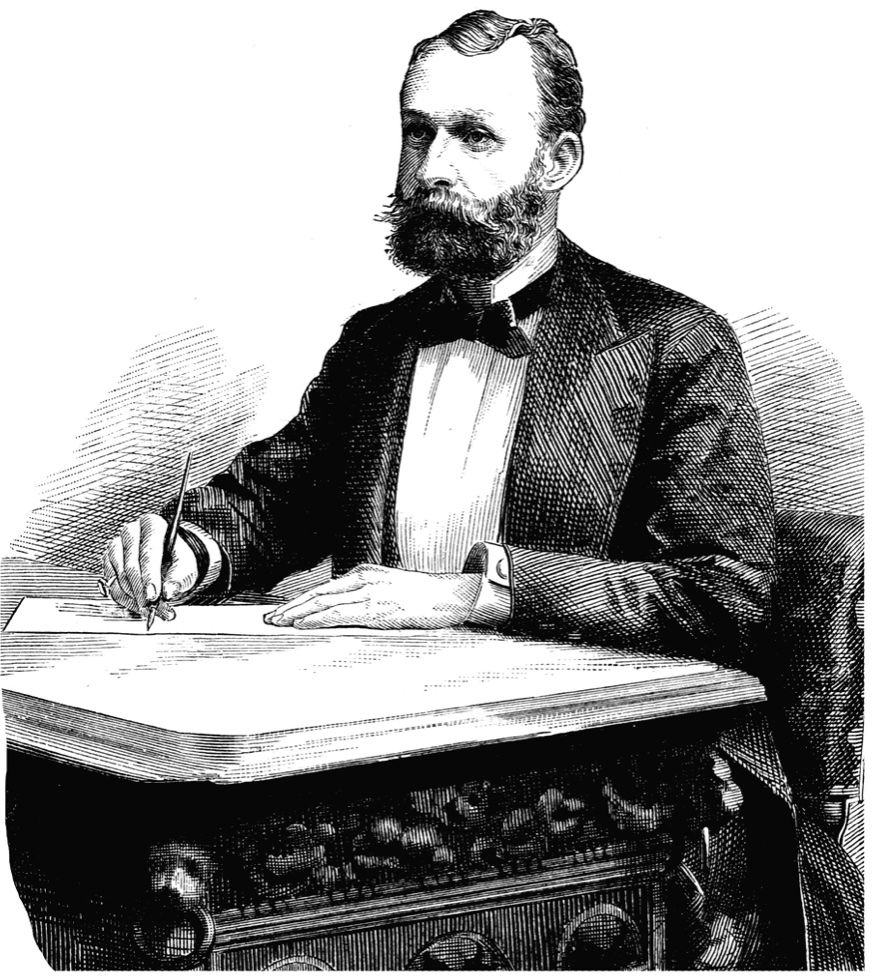

Although he was born frail and sickly, in 42 years he left behind a bafflingly insightful and beautiful body of work. His writings appeared under the names of nearly a dozen pseudonyms. He has been called philosopher, theologian, preacher and even poet, yet he said, “My existence itself is really the deepest irony.” In the 200th year since his birth, Søren Kierkegaard still possesses the coyness of the Cheshire Cat, disappearing at will, leaving only his grin behind. But behind the tricks, disguises and illusions is the Kierkegaard the 21st century urgently needs: Kierkegaard the educator.

Kierkegaard preferred to use the term “upbringing” rather than “education.” Upbringing encompasses the growth of the whole human person—not just the mind. For Kierkegaard meaningful education does not end in knowledge, but in the realization of knowledge. An upbringing is not complete until learning influences the life of the student. A teacher cannot bring up a student by teaching abstract theories like Kant’s “categorical imperative,” nor can a student be brought up with so-called “practical” learning—how to build a bench, interview for a job or input a VLOOKUP formula in Microsoft Excel. Kierkegaard believed that overly practical education—education only concerned with how questions—would create what he called “fractional” human beings: people who are trained to do a particular task rather than to strive for personal transformation.

Kierkegaard’s revolutionary insights about the nature of upbringing led him to question the value of information itself. In Kierkegaard’s age new printing technologies allowed newspapers and journals to reach a mass audience with much greater speed than ever before. Kierkegaard sensed that these new developments led his contemporaries to the faulty assumption that the “knowledge” produced by information was an end in itself. He even pointed out that information can get in the way of authentic living, complaining that “the whole mob of publishers, book-sellers, journalists, authors” distract from the truth that “relatively little knowledge is needed to be truly human.” The new technologies and trends emphasized extensive knowledge to the exclusion of intensive knowledge, the knowledge that affects us personally and intimately, and alters our way of living. Kierkegaard insisted that without real upbringing, information is meaningless.

As an example, Kierkegaard tells the following story:

A sergeant in the National Guard says to a recruit, “You, there, stand up straight.”

Recruit: “Sure enough.”

Sergeant: “Yes, and don’t talk during the drill.”

Recruit: “Alright, I won’t if you’ll just tell me.”

Sergeant: “What the devil! You are not supposed to talk during the drill!”

Recruit: “Well, don’t get so mad. If I know I’m not supposed to, I’ll quit talking during the drill.”

In this story the recruit is able to receive the necessary knowledge from the sergeant and yet the knowledge doesn’t alter his actions or his attitude. The recruit fails to see that the sergeant does not aim to simply inform him, but to transform him into a soldier. The sergeant, Kierkegaard explains, will have to use indirect communication like drills, challenges and exercises to shock, startle and shake up the recruit. He will have to communicate not only to the recruit’s mind, but to his will, desires, goals and his life project. This shows why, as Kierkegaard also wrote, “to bring up human beings is a very rare gift.”

Today’s nearly instant communication and vast stores of online information make the technology of Kierkegaard’s age look primitive. We are more fast-paced, more analysis-driven and more practically minded in our education than any society early 19th century Denmark could have imagined. We pride ourselves on outsourcing thinking to software and memory to “the cloud.” Perhaps most tellingly, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are quickly becoming the new paradigm for “progressive” education. MOOCs are enormous—courses reach tens of thousands of students at a time. Widely available and often at very low cost, MOOCS involve a minimal commitment from students, making it easier than ever to confuse a wealth of information with total education or upbringing that Kierkegaard reminds us to strive for.

The kind of teaching that Kierkegaard wrote about is not so much under threat as it is forgotten. This March, announcing that he would leave the teaching profession after over forty years of service, Gerald Conti wrote that his “total immersion” approach to teaching is “not only devalued, but denigrated and perhaps, in some quarters despised” in favor of a “data-driven” approach. He concluded his resignation by stating,

“I am not leaving my profession, in truth, it has left me. It no longer exists. I feel as though I have played some game halfway through its fourth quarter, a timeout has been called, my teammates’ hands have all been tied, the goal posts moved, all previously scored points and honors expunged and all of the rules altered.”

Countless teachers like Gerald Conti are struggling to make their voices heard, insisting that the art of teaching is not scalable, marketable or packageable and that it does not lend itself to our demands for efficiency, predictability, calculability and control. Teachers insist that they are more than knowledge transfer technicians who streamline and facilitate a download of information into their students’ heads. Their job is not always to make things easier, but sometimes to make things difficult. They don’t simply grease the wheels of the educational machine; they provoke, prod, challenge and upset, doing whatever it takes to break through the passive consumerist mentality that makes us receivers of knowledge and not active participants. Put simply, they remind us that, unlike MOOCs, upbringing always costs something. It demands pain, time, energy, focus, passion and diligence.

If upbringers want to make an impact on the 21st century, they will have to be more elusive, more artful, more sly and more creative than ever. And when they’re ready to learn they can look to Kierkegaard the educator, the master magician with the Cheshire Cat grin.

[i] Kierkegaard, Søren. Søren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Papers. Edited and translated by Howard V. and Edna H. Hong