It’s a wonder that Richard Linkater’s new movie Boyhood ever got funded, because on paper the story must have sounded really boring: a brother and sister complain about moving, go bowling, go to school. They go to a baseball game with their dad. They jump on a trampoline. They have lots of walk-and-talks. Not to mention the fact that Linklater was also asking for a 4,207 day shooting schedule. But thank goodness for the plucky executive who gave the gutsy green light, because Boyhood is a film that is much bigger than the sum of its mundane parts.

In his essay, which Emily Belz cited in her review for WORLD, “E Unibus Pluram” David Foster Wallace critiques the

stylized conceitsof contemporary cinema and television as meretriciously catering to our desire to transcend our average daily lives. These hysterical collages are, in his words, “unsubtle in their whispers that, somewhere, life is quicker, denser, more interesting … more lively.” We leave these films dazzled, punching the air, ready to do combat with a gang of bad guys or lose a pursuer in a car chase, but we enjoy none of the edifying potential that Leo Tolstoy and other early theorizers of cinema’s potential saw in the fledgling art form.

Contemporary independent cinema often works in stubborn self-conscious contrast to the transcendence aesthetic, but too often the results are aimless, dreary, overly abstract, and riddled with dead points. It is only once in a great while that a film eschews the comparatively easy luster of dreams and manages to turn the stuff of our average daily lives into something magical. Boyhood is one of these rare films.

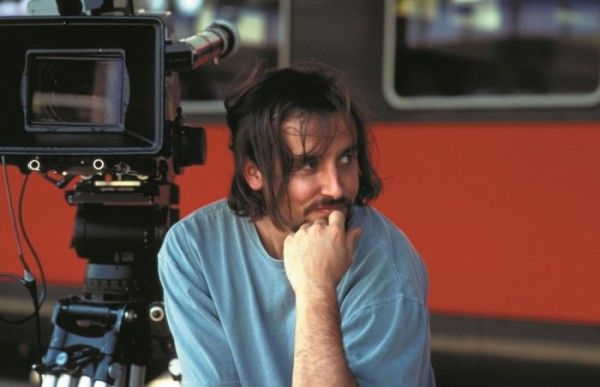

In the late 1990s Linklater began to process a specific inclination to depict the 12 years of public school that is the average American childhood. His conception of this work, however, repeatedly ran aground against the problem of time limitations imposed by the physicality of actors. He meditated on the problem for two years until, like Archimedes in his bathtub, an elegantly simple solution presented itself—provide time for the actors to age along with their characters.

Boyhood focuses on the lives of Mason (Ellar Coltrane), mother Olivia (Patricia Arquette), father Masor Sr. (Ethan Hawke), and sister Samantha (Lorelei Linklater, the director’s daughter) over the course Mason’s rather ordinary childhood. What makes the film remarkable is that Linklater shot the film in short annual increments over a period of 12 years. He then collapsed this collection of segments seamlessly into a 3 hour feature. Thus the film not only depicts a story arc, but also the actual physical and emotional maturation of the characters (and actors) as they age. The effect, like human time-lapse photography, is breathtaking.

If great art, like science, advances through problem solving, then Linklater is the ‘scientist’ to make this breakthrough. This latest temporal experiment is the culmination of an increasingly sophisticated body of work preoccupied with the subject of time. These films include Tape (2001), which unfolds in real time, Waking Life (2001), which evokes the experience of a continuous dreamlike present, and most notably his Before Sunrise/Before Sunset/Before Midnight trilogy. These three films—chronicling love and marriage, spanning 18 years, and shot in fictional 6 year increments—come closest to the formal experimentation and thematic concerns of Boyhood.

Although similar in structure and concept, the impression of time created in the Before Trilogy is distinct from Boyhood. The Before films are remarkable for tracking the vicissitudes of a relationship—the longing, romance, frustration, and disappointments—over an 18-year period. But taken together, the films play as a series of vignettes, suggesting that, rather than a continuous progression, time moves in fits and starts, in sprawling years punctuated by intensely dramatic moments. Boyhood, because of its tighter narrative arc and shooting schedule, creates a markedly new sense of the progression of time. Just as time-lapse photography allows for normally imperceptible phenomena to be observed (plants growing, for example), Boyhood reveals the interstices between the dramatic events of childhood, in which memories are made and real life is lived.

It is not only the unconventionally long shooting schedule of Boyhood that captures this resonant experience of time and memory, but also Linklater’s choice to keep the momentous and melodramatic events of childhood at the periphery of the film. The film functions like a subjective memory of childhood, where the big events often take second-tier status to quieter moments and memories that remain embedded in our consciousness and puzzle us by their lack of significance.

In an early scene in the movie, a young Harry Potter-reading Mason asks his father: “Is there any real magic in the world?” His father answers:

“…. what if I told you a story about how underneath the ocean there is this giant sea mammal that can use sonar and sing songs and it was so big that it’s heart was as big as a car and you could crawl through it’s arteries. You would think that’s pretty magical right?”

In the same way, by skirting the momentous events of childhood and allowing its gaze to rest gracefully on the quotidian, Boyhood evokes what is wondrous and memorable in everyday life.

As late as the editing process, Linklater and his team were considering titling the movie “Always Now.” The final bit of dialogue in the film expresses this dominant theme of the passage of time. Mason and a friend muse that rather than the platitude “seize the moment” being true, the moment seizes us. “The moments are constant. It is always right now,” says Mason.

In choosing the title Boyhood, though, Linklater acknowledges that there is more to the film than a meditation on the passage of time. The film’s pathos resides there.

Part of the film’s pathos resides in the tension between the thrill and potential of the future and the persistent sense that the march of time is relentless and the past is irretrievable. There is hope and excitement as we see Mason realize potential and independence, but also tragedy. Upon sending her son to college, Mason’s mother weeps and holds her head in her hands considering the series of milestones that has been her life and the fact that her funeral is the next to come, she laments: “I just thought there would be more.”

This chafing for something more in the face of one’s mortality is an articulation of what the modernist poet Wallace Stevens called “the need of some imperishable bliss.” It is a desire for transcendence more fundamental than the desire to escape from our lives through entertainment that David Foster Wallace so aptly identifies. It is the hope of coming into contact with something bigger than ourselves, something “more,” something outside of time. In Escape From Evil, Ernest Becker calls this man’s desire “to know that his life has somehow counted,” but, “in order for anything once alive to have meaning, its effects must remain alive in eternity in some way.”

“…in order for anything once alive to have meaning, its effects must remain alive in eternity in some way.”

For all of its intelligence and sensitivity, like much of contemporary narrative, Boyhood vividly traces the contours of this desire for the transcendent at the center of the modern psyche but offers little insight into how it might be healed. Because the making of the film not only spanned 12 years in the lives of its actors but also 12 years in Linklater’s own life and career, the viewer cannot help but think about how the director has changed over the period.

In contrast, Linklater’s early, and granted, less mature, films are doggedly concerned with questioning the possibility of encountering the transcendent. Near the end of Waking Life, Linklater himself addresses the camera with a spiel about his favorite topic:

“There’s only one instant, and it’s right now, and it’s eternity. And it’s an instant in which God is posing a question, and that question is basically, ‘Do you want to, you know, be one with eternity? Do you want to be in heaven?’ And we’re all saying, ‘No thank you. Not just yet.’ And so time is actually just this constant saying ‘No’ to God’s invitation. And there’s just this one instant, and that’s what we’re always in. And actually this is the narrative of everyone’s life. That, you know, behind the phenomenal difference, there is but one story, and that’s the story of moving from the ‘no’ to the ‘yes.’ All of life is like, ‘No thank you. No thank you. No thank you.’ Then ultimately it’s, ‘Yes, I give in. Yes, I accept. Yes, I embrace.'”

Although Boyhood is a cinematic achievement that won’t soon be eclipsed, it’s hard not to feel a little nostalgic for the more impetuous and philosophically adventurous Linklater of 13-years ago, an artist who seemed open to a magic beyond the quotidian. Regardless, it’s impossible to be a movie lover and not feel excited to see what this innovative director does next.