When James Baldwin’s famous account of America’s race crisis, The Fire Next Time, was first published in 1963, the critic Frederick Wilcox Dupee penned a review in the February issue of The New York Review of Books, which begins charitably enough: “As a writer of polemical essays on the Negro question James Baldwin has no equals.” But from this point onwards, Dupee’s review devolves into condescension. Dupee’s thesis is that Baldwin “exchanged prophecy for criticism, exhortation for analysis, and the results for his mind and style are in part disturbing.” After dismissing out of hand Baldwin’s epistle “My Dungeon Shook” as “not good Baldwin”—leaving the reader to wonder just what Dupee means by “good Baldwin”—Dupee turns to the much more famous and extensive second portion of the book, “Down At the Cross: Letter From a Region of My Mind.” Dupee admits that much of what is found here is “unexceptionably first-rate,” praising Baldwin’s account of his childhood and his “data” on the Nation of Islam—the content of Baldwin’s brief interview with the movement’s leader, Elijah Muhammad. But against the analysis that Baldwin levels against Dupee himself, as a member of the white majority and shareholder in white power as a critic of art, Dupee mounts a defense. He begins with a quote from Baldwin:

“’White Americans do not believe in death, and this is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them.’ But suppose one or two white Americans are not intimidated. Suppose someone coolly asks what it means to ‘believe in death.’ Again: ‘Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?’ Since you have no other, yes; and the better-disposed firemen will welcome your assistance. Again: ‘A vast amount of the energy that goes into what we call the Negro problem is produced by the white man’s profound desire not to be judged by those who are not white.’ You exaggerate the white man’s consciousness of the Negro.”

Aside from providing a list of now-iconic lines from Baldwin, Dupee reveals his own prejudice and fear in his rebuke of Baldwin’s attempts to make clear the parameters and effects of systemic racism. In questioning what it means to believe in death, Dupee’s own ambivalence and ignorance is exposed; Dupee ironically shows that he himself does not know. Dupee’s final proposition, that Baldwin “exaggerates the white man’s consciousness of the Negro,” reinforces a reality that Baldwin himself articulated in terms that were nothing less than luminous: the complete lack of whites’ consciousness of black life. Perhaps if he had not so quickly glazed over “My Dungeon Shook,” Dupee would have realized that Baldwin had described this same unconsciousness: “I am writing this letter to you [Baldwin’s nephew], to try to tell you something about how to handle them [whites], for most of them do not yet really know that you exist.”[1]

+++

Dupee’s review aside, The Fire Next Time is widely regarded today as a classic of literature, and essential reading for any student of race in America. In the two essays that comprise the small book, James Baldwin describes the status of the African American persons in American society, the religious ramifications of race, and the necessary response. The book’s brilliance is that it offers criticism that is both cultural and constructive—a point that Dupee fails to appreciate, even if he rightly identifies Baldwin’s prophetic tone. This tension, between constructive prophecy and criticism, has been born out throughout African American literature, and the dialectic remains apparent today in Baldwin’s successors. Baldwin’s legacy reveals an ongoing conversation in African American literature between the impulse to place hope in a future that has not yet come, and the urgent need to protect the body and safeguard African American life in the present.

This conflict has much to do with the historic relationship of American Christianity to both African American oppression and liberation; a topic that is well beyond the breadth of this discussion. Nevertheless, in much contemporary African American literature, there is a tendency to attend to the black body and threats posed to it by whiteness, and to see this attention as being at odds with constructive prophetic discourse. By this line of thinking, attention to the present means an attention to the body, and to attend to a hoped-for future is to separate oneself from life as it is truly lived. Few would disagree with the truth that defense of the body is defense of life. However, there is a life-giving aspect to prophecy as well, and “good Baldwin,” Baldwin at his best, critiques the bodily abuses of the present through both anthropological criticism and outward attention to prophetic hope.

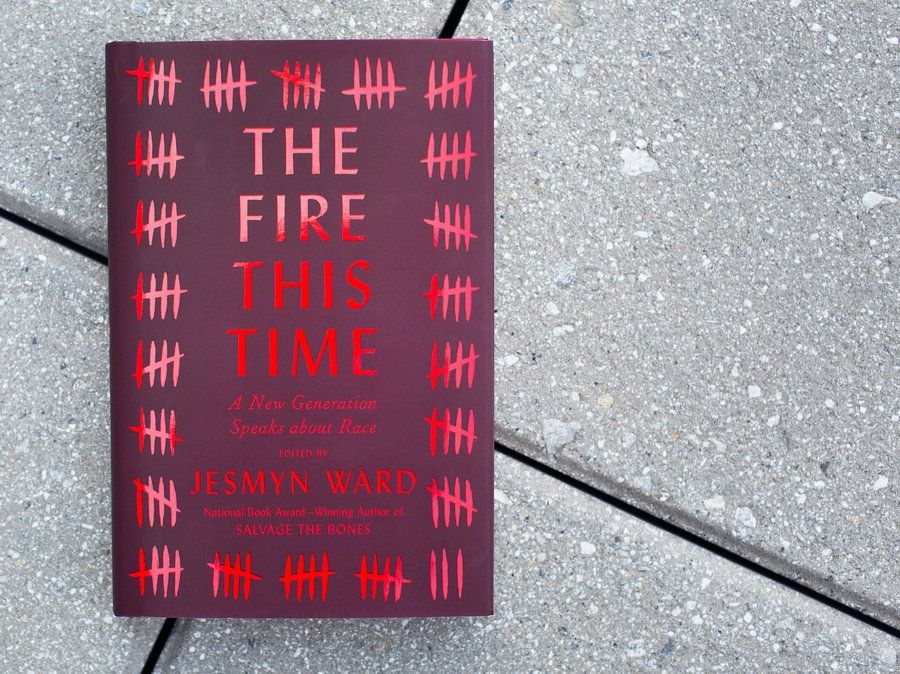

Over the past year, Baldwin’s legacy has been taken up by Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jesmyn Ward. Jesmyn Ward’s new anthology, The Fire This Time, is a spiritual sequel to Baldwin’s incendiary work, and Coates’ Between the World and Me offers a Baldwin-esque bildungsroman, narrating the experience of growing up black in a white nation. These writers are re-embodying Baldwin’s voice for an America that remains as racialized and divided as ever.

+++

In her introduction to her anthology The Fire This Time, Jesmyn Ward identifies a crucial fact that Dupee missed, and which Baldwin knew well: Baldwin wrote for a black audience in a white world. In the aftermath of the killing of Travyon Martin, Ward “realized that most Americans did not see Trayvon Martin as I did.”[2] There was little understanding of Martin’s death as a tragedy outside of the black community, leading Ward to realize that Martin’s embodiment meant something different to non-black Americans.[3] In the wake Martin’s death, the experience of reading Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time transported Ward: “It was as if I sat on my porch steps with a wise father, a kind, present uncle, who… told me I was worthy of love.”[4] Ward felt inspired to re-present this tradition—passing the torch of struggle to a new generation of black children, activists, and thinkers—through an anthology. As an anthology, Ward’s book offers a catalogue of powerful, visionary voices, a community in which a frightened child might find “a wise aunt, a more present mother, who saw her terror and despair threading their fingers through her hair, and would comfort her.”[5] The result of Ward’s formal decision to assemble an anthology is that Baldwin’s voice is multiplied through many mouths, making The Fire This Time a recalibration and expansion of Baldwin’s original message for the present.

The book is divided into three segments, oriented to past, present, and future: Legacy, Reckoning, and Jubilee. Legacy and Reckoning consumes the bulk of the book, while Jubilee is relegated to the final twenty pages. Ward bemoans this fact, but also acknowledges its underpinnings: the past is “inextricably interwoven… in the present” and yet “bears on the future.”[6] Ward also admits to “a certain exhaustion,” an exhaustion no doubt felt across the African American community in 2016.[7] It’s hard to speak of jubilee, of prophecy, when racial violence and futility appear at every turn. To imagine a different future is difficult for Ward, and if her anthology is deficient, it is due to a deficit of the imagination; a deficit born of suffering, but a deficit nonetheless.

The future remained very much in view at the end of Baldwin’s essay. The final lines of “My Dungeon Shook” roar of Biblical judgment and justice: “God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!”[8] This line, taken from a slave spiritual, does not refer to the fire of revolution, but to the fire of judgment. This is a fire that brings resolution and justice; a fire that signals not the endurance of struggle, but the end of struggle. Baldwin meant to speak of fire as a warning; judgment is coming, and we ought to prepare ourselves. This was the religious angle that Dupee saw and feared. When Ward invokes Baldwin’s prophecy in the title of her own anthology, she is representing this religious voice, but blunting its prophetic edge. To speak of the fire this time means to look for the fire again and again, in the present. The future is awash in doubt, and justice is far from a forgone conclusion. For Ward, the sin of racism and racialized violence is one that must be repented of forever, without end. As a permanent, immovable brand on the American consciousness, there will be not one, but many judgments. That is why the central chapter of Ward’s collection bears the name Reckoning; and Ward’s is a sense of reckoning has to do more with taking account of the state of things, rather than hoping for a new reality.

Aside from shifting Baldwin’s prophetic voice form the future to the present, Ward offers a different sort of rationale for the task of exposing America’s racist history. Of her new collection, Ward writes, “I believe there is a power in words, power in asserting our existence, our experience, our lives, through words. That sharing our stories confirms our humanity.”[9] The rationale for Ward’s collection is an anthropological one, rooted in narrative. In sharing stories, we are speaking and empower ourselves. There is an inward turn here, to sharing the self, and in so doing, liberating the self, and confirming the self’s perception of the world. Baldwin’s turn is quite the opposite, focused outward. In “My Dungeon Shook,” Baldwin writes to his nephew James of a different kind of commitment. Not a commitment to reckoning, but a commitment to love.

“There is no reason for you to try to become like white people and there is no basis whatsoever for their impertinent assumption that they must accept you. The really terrible thing… is that you must accept them. […] You must accept them and accept them with love. For these innocent people have no other hope. They are, in effect, still trapped in a history which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.”[10]

This is a provocative piece of writing. In the context of black liberation, acceptance and liberation—turned towards the white oppressor—seems incredible. Baldwin is asking his nephew to love his white neighbor away from the inhibitions which keep her from seeing him as he is: fully human, and capable of both giving and receiving love. While Ward’s anthology offers space to vent and discuss trauma, Baldwin’s text is a call to neighbor-love: “these men are your brothers—your lost, younger brothers.”[11]

Baldwin’s call to love is a call to an identification of the other, not identification of the self: “we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are.”[12] Baldwin knows who he is, and so he can identify the other. One senses from Ward, and from her colleagues, that the racial crisis of the twenty-first century is one of self-identification. Ward’s anthology focuses on issues relevant to black identity: Rachel Dolezal’s imitation of blackness, the complexities of family heritage, knowing one’s rights in a police state, and the condition of black life. These are all internal concerns which Baldwin himself knew well, crimes “for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive.”[13] And yet Baldwin does condescend, through his anger and hurt, to offer something to the wicked innocence of whiteness, to love his white neighbors by revealing to them their crimes, and in so doing, find healing.

+++

Like Ward, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ also reckons with the realities of his time, and evokes Baldwin’s own aesthetic through his beautiful syntax and searing critique. Ta-Nehisi Coates’ ascension to the mantle of Baldwin has been met with some controversy, however, largely due to Coates’ assertion that Baldwin’s method—the way of love—cannot stop bodies from piling in American streets.

“…all our phrasing—race relations, racial chasm, racial justice, racial profiling, white privilege, even white supremacy—serves to obscure that racism is a visceral experience, that it dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth. You must never look away from this. You must always remember that the sociology, the history, the economics, the graphs, the charts, the regressions all land, with great violence, upon the body.”[14]

Between the World and Me is a letter to Coates’ son, sharing Baldwin’s epistolary form. But of Baldwin’s letter lays the burden of love upon his nephew James, Coates wants nothing more than to see the burden lifted from his own son. Coates will not condescend to Dupee and other whites in the service of a better world. To his son, he writes “the birth of a better world is ultimately not up to you. […] You are a black boy, and you must be responsible for your body in a way that other boys cannot know.”[15] Likewise, Coates has no time for the ideals that Baldwin espouses, prophecy in particular: “You must resist the common urge toward the comforting narrative of divine law, toward fairy tales that imply so irrepressible justice.”[16] In Coates’ uncompromisingly physical world, a black boy’s only responsibility is for himself, and for the actions of other black bodies. Coates’ tone is not cynical, but realistic. He is frank about the realities he sees, and his hope is agnostic at best.

And yet Coates is not immune to the fairy tales he condemns. Coates’ unique take on Marvel Comics’ Black Panther shows that Coates has at least a propensity to entertain other realms than the world of flesh and blood in which he lives. Like Baldwin, Coates is searching for something imaginative—perhaps we can call it an eschatology, but it may be better described as a mythology—to mediate the crisis in the streets. Coates writes how as a child “I found the tales of comic books to be an escape, another reality where, very often, the weak and mocked could transform their fallibility into fantastic power.”[17] Coates’ fascination with comic books is not unlike Baldwin’s own fascination with religion. In “Down at the Cross,” Baldwin writes of the thrill of worshipping:

“It took a long time for me to disengage myself from this excitement, and on the blindest, most visceral level, I never really have, and never will. […] There is still, for me, no pathos quite like the pathos of those multicolored, worn, somehow triumphant and transfigured faces, speaking from the depths of a visible, tangible, continuing despair of the goodness of the Lord.”[18]

The hypocrisies of the church were not lost on Baldwin,[19] but he understood the imaginative power, the motifs, that religion could offer him. Coates, no doubt, sees something similar in the mythic world of superheroes. The Marvel Universe, like the Christian tradition, is populated by transformed and empowered individuals. Coates’ realism is thus punctuated by something like the Biblical motifs that Baldwin himself draws upon, even if their worldviews are at odds.

+++

Time will tell whether the literary offerings of Ward and Coates will retain the enduring value of Baldwin’s own work. In the present, they render interesting reinterpretations of Baldwin’s legacy, seeing in Baldwin both inspiration for and divergence from their own view of America’s race crisis. Ultimately, their differences are philosophical: both Ward and Coates speak with frank realism, while Baldwin himself was nothing less than an idealist, believing that human beings have the capacity to do better:

“If we—and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others—do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world.”[20]

Baldwin’s is a high calling, and perhaps, more than fifty years after the publication of The Fire Next Time, other writers are correct to question whether it is too high. Regardless, Baldwin’s followers have not lost his prophetic voice and his certainty, the borderline-religious conviction that Dupee could not stand. Dupee has no time for prophecy. Rather than dealing with Baldwin on Baldwin’s terms, Dupee would rather be dealing with a black man remade in his own white image: “When Baldwin replaces criticism with prophecy, he manifestly weakens his grasp of his role, his style, and his great theme itself.” By this, the end of Dupee’s review, it’s unclear just what “great theme” Dupee has in mind. On this point, “My Dungeon Shook” could have offered Dupee a saving insight: these words are not for him. Dupee finds in Baldwin’s work a storm of fear and confusion, but so would anyone who is guest to a conversation between individuals they know little of and care little for.

But Baldwin’s great theme—his prophetic certainty that America places itself under imminent judgment—no longer requires a critic’s endorsement. It has been carried on well enough in our time. Baldwin’s history speaks for itself. The critic’s role, and the role of Baldwin’s heirs, is now to assess how close we stand to the imminent blaze that the great man foresaw. It may be that we are engulfed already.

[1] James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, “My Dungeon Shook,” 6.

[2] Jesmyn Ward, “Introduction” in The Fire Next Time, 4.

[3] Ibid., 6.

[4] Ibid., 7.

[5] Ibid., 8.

[6] Ibid., 9.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, 106.

[9] Ward, “Introduction,” 10.

[10] Baldwin, “My Dungeon Shook,” 8.

[11] Ibid., 9.

[12] Ibid., 10.

[13] Ibid., 6.

[14] Ta-Nehesi Coates, Between the World and Me, 10.

[15] Ibid., 71.

[16] Ibid., 71.

[17] Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Return of Black Panther” in The Atlantic, April 2016. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-return-of-the-black-panther/471516/

[18] Baldwin, “Down at the Cross” in The Fire Next Time, 33.

[19] Of his experience in the church, Baldwin writes “I was… able to see that the principles governing the rites and customs of the churches in which I grew up did not differ from the principles governing the rites and customs of other churches, white. The principles were Blindness, Loneliness, and Terror.” Baldwin, “Down at the Cross,” 31.

[20] Baldwin, “Down at the Cross,” 105.