Peace Like a River begins with a miracle. Helen Land gives birth to a son, Reuben, but instead of the typical, healthy shrieks of newborn fear, his lungs did not cooperate with the rest of his anatomy. Reuben himself steps in to the narrative to say, “I was gray and beginning to cool. A little clay boy is what I was.” His father had been pacing and praying outside, but with prodding from God, he ran inside to the delivery room. Jeremiah lifted his ashen son and commanded in a normal voice, “Reuben Land, in the name of the living God, I am telling you to breathe.” The baby obeyed, his chest received and released sweet air, and my eyes bugged.

Just fourteen pages later Jeremiah paced again – this time on the bed of a grain truck – and prayed again. Intercession is kind of a big deal for this guy. He was immersed in his petitions, visibly troubled, lips moving, clenched fists pressed to his closed eyes. Reuben interjects into his narrative, “Did I say earlier that the flatbed sat up off the ground about three feet? Because I should have; it matters here.” As the young boy watched from behind the corner of a barn, his Dad walked right off the edge of that truck onto approximately a yard of thin air, above thistles and thatches of tall grama which waved as if blown by the wind. He paced about thirty feet, paused, and returned. He did not fall, nor was he aware of his supernatural acrobatics. Reuben was caught off-guard to hear his own name within Jeremiah’s unsettled pleas.

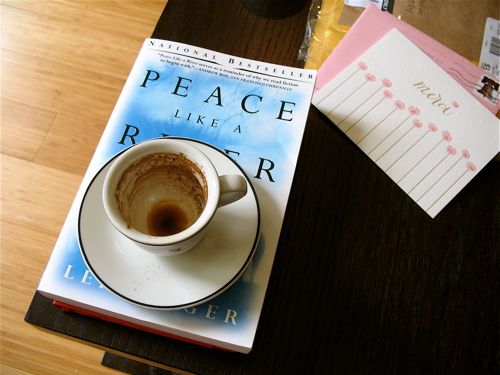

At the precise moment I read this extraordinary scene, the light bulb in a nearby lamp burnt out with an abrupt click. I can be a little dramatic, so I gasped. I could see the fictional moonlight, no matter my own Houston sunlight. I heard Jeremiah’s steady footsteps on the flatbed, then “his feet noiseless, hitting nothing.” A miracle occurred right before my eyes without any flowery prose. This is the marvel of Leif Enger’s sparse, yet poetic writing. It’s as if no time can be wasted to introduce stark realities and supernatural goings-on. Nor can beauty be spared to hearten the soul with old-fashioned prayer, miracles, and the possibility of what these familiar personalities have up their sleeves.

Characters Familiar and Complex

Enger acquaints us with Reuben so dramatically because he is a witness – to his father’s otherworldly handiwork, and to a crime. Though he lives and breathes, it is the labored effort of asthma, perhaps to help him keep his head. He beholds the world with the same matter-of-fact insistence of the New Testament epistle writers, invading the personal space of whoever might serendipitously pick up the book:

I believe I was preserved, through those twelve airless minutes, in order to be a witness, and as a witness, let me say that a miracle is no cute thing but more like the swing of a sword.

He talks like that the whole time, remembering his eleventh year, which makes for an epic yarn of a tale set in 1960s Minnesota. And as both a witness and storyteller will do, he observes everyone and every event surrounding him with wit, wisdom, and tender vulnerability. It’s not a comfortable story to ease into. Along with the preternatural, there’s an early foreboding, adventure, and a close-knit, complex family. Through Reuben’s eyes, the whole crew barged into my psyche. He loved them, and so I couldn’t help myself.

Jeremiah is a humble janitor, as unassuming as one could be while performing the miraculous. He’s a kind, easygoing fellow, yet fiercely protective of his children. Reuben often operated as a pair with his younger sister – I’m not sure there are words to describe the likes of towheaded Swede. She was typically drawn to unladylike or age-inappropriate activities: hunting, playing with dead geese feet, and reading Robert Louis Stevenson, Zane Grey, and historical accounts of heresy. Her vocabulary is impressive, and she once snickered when someone said “onus eye” instead of “evil eye.”

Then there’s the eldest: sixteen-year-old Davy, very complicated and strong. He and his Dad butt heads in the early miracle-packed pages regarding Jeremiah’s involvement in a conflict with two infamous town thugs. Davy disagreed with his father’s definition of justice. Reuben described his brother as having “Dad’s own iron in his spine”, but not his heart. When their own family’s safety was threatened, Davy shot their enemies dead, rendering himself a fugitive. Jeremiah and the young children set out to find the wayward son in the North Dakota Badlands. Swede penned a Western epic to mirror and foreshadow the imminent events of their journey inspired by the sacred, the godless – Old Testament grandeur and vintage police dramas.

A Cult Following

I’m an avid reader and used to work in a bookstore, so I have a compulsion for recommending great books. I’ve taken my compulsion to a whole other pesky level with this 2001 bestseller. It is too broad for one genre, but it does modernize and revive the Western. Two of my own heroes, my grandfather and father-in-law, lived and breathed the Old West, wore cowboy boots and bolo ties, and loved reading Westerns. For me, reading Peace Like a River breathed new life into my respect for a good Western – though Enger’s version replaced a horse with the Land family’s silver Airstream trailer. Davy is the lone, good-natured renegade running from a federal agent. Further down the trail is the persona of evil, Jape. And there is chivalry from Jeremiah, Rube, and Swede toward a friend, Roxanna, who offers them shelter. She changes before their eyes with something like the Transfiguration. For as Swede said, “every Western is a love story, you see.” And this love is reflected everywhere in the Land family: a father to his volatile son, the son toward his family, young siblings to their father and brother, and a family toward this new free-spirited lady friend. Enger plumbs the depths of all this with a shimmering beauty of a plot that I can’t divulge to spare you the spoilers.

Peace Like a River‘s cult following is also formed by the depiction of a wholesome family without a load of dysfunctional garbage. Mrs. Land did leave town and Davy is a wild card, but the bonds between Jeremiah and his children are unusual. Fathers are not typically portrayed in such a respectful light, in a literary landscape in which men are feminized and fathers are derided. Enger’s Jeremiah is different, a man of good character and integrity. He’s honest and cares for his children; he loves them sacrificially and believes in their potential. He is the kind of man to sit down at the kitchen table with a cup of coffee and the King James Bible, a hymn upon his lips. We need that kind of man back in our imaginations and in our lives – a real hero.

Faith on the Bestseller List

To write about faith well is tricky. To write popular fiction that espouses Christianity so unapologetically is even more precarious. Yet Leif Enger succeeded, writing a book with broad appeal with appeared on several bestseller lists including Time magazine, The Los Angeles Times, and The New York Times. No matter what a Christopher Hitchens might say, the culture craves both good art and faith. Not one or the other, but an artful belief in the God who gave miracles to Jeremiah’s hands.

The faith of Peace Like a River is not a mere panacea. Tragedies certainly occur. But Enger paints faith to be just what it is – the gutsy notion that all will be well despite the evidence before you. He also gives an honest portrayal of humanity in the Land family as they travel to find Davy with ambiguous intentions. As a federal agent catches up with the family, he asks for help to locate the refugee, and Jeremiah struggles viscerally, even intimating disapproval in his prayers. Faith is rehumanizing, but it’s a bold art for any man to master.

Leif Enger’s most brilliant accomplishment is to make the supernatural believable and palatable through Reuben’s sincerity. Instead of mawkish sentiment, he relates, “Real miracles bother people, like strange sudden pains unknown in medical literature. It’s true. They rebut every rule all we good citizens take comfort in. Lazarus obeying orders and climbing up out of the grave – now there’s a miracle, and you can bet it upset a lot of folks who were standing around at the time. When a person dies, the earth is generally unwilling to cough him back up. A miracle contradicts the will of the earth.”

Most days, I fully expect to see miracles, yet I’m just as much human as I am spirit. I long for wonder, but I’m sure accustomed to this earth. Peace Like a River inspires a faith in the supernatural, an almost artistic endeavor requiring something akin to imagination. I read Peace Like a River when I was first diagnosed with a few health issues and embarked on a slow trek to healing. I took Reuben’s asthmatic affliction to heart when he said, “The infirm wait always, and know it.” Reading this novel was timely, boosting my tenacity. I was ready and primed with a weary body and a heart ravenous for the seemingly impossible.

Madeleine L’Engle once said that story erases physical pain. If you are immersed in story, you forget pain. And if the story shines goodness and truth, we take to it like a child with a unflinching belief in the magical. Jeremiah never summoned the miracles. They were God-given, sometimes odd and freakish, but always gleaming with realism right ’til the breathless climax.

Through Reuben Land’s robust, conversational narration, we are encouraged by the restorative power of literature. Peace Like a River is a comforting book in these days of anxiety and uncertainty. But it is not merely a story by which to escape, though. Reuben asks something of you, the reader:

Is there a single person on whom I can press belief?

No sir.

All I can do is say, Here’s how it went. Here’s what I saw…

Make of it what you will.