Yesterday I went to a museum all by myself.

Like most Americans, I used to go to museums mostly for class field trips. This type of museum-going tends to be more a social experience in which the group tries to see the greatest number of pieces, limited only by time and physical exhaustion. By contrast, yesterday was about the art-about seeing it and looking at it, and learning to receive it.

Yesterday’s trip was my first time going to a museum with an art-viewing framework that wasn’t in the form of a checklist. Only six months ago, I took my college’s required “Civilization and the Arts” course, the underlying tenet of which was a distinction between the “use” and “reception” of art, as C.S. Lewis explains in An Experiment in Criticism. Lewis tells us that in order to receive a work of art, “We must look, and go on looking till we have certainly seen exactly what is there,” or, in the words of my professor Dr. Munson, “Look and see!” This simple directive has not only liberated me from the school teacher’s “Go and check-mark,” but has also provided a source of confidence in art appreciation on the whole.

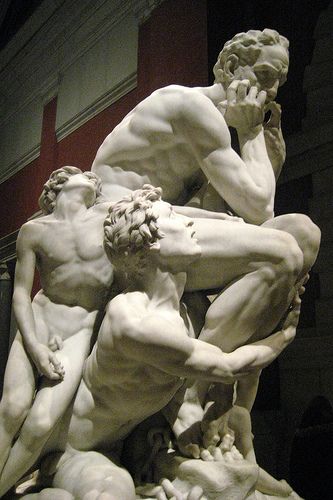

But do not be deceived (O Reader!): what this three-word sentence lacks in complexity, it makes up for in demand. Looking and seeing may not require vast amounts of art history education, but these are by no means activities of ease; in fact, they may leave you far more exhausted than the walking. The first – and last – work I really looked at and saw yesterday was Jean-Baptiste’s Carpeaux’s Ugolino and His Sons.

As I trekked for the three miles from the bus terminal to the Museum, I began to remember the art we had studied in class, and I felt a sense of excitement begin to swell as I realized that where I had once seen images of art, I was now going to see art. I especially wanted to see sculptures, as two-dimensional slides are particularly cruel to them, so I hoped for the works of Michelangelo and Bernini. Not having done my homework, however, I was disappointed to find that the Met does not carry any sculptures by Michelangelo, and while I was grateful for Bernini’s Bacchanal: A Faun Teased by Children, it would be Ugolino & Co. that stood as the greatest test for everything I learned in class.

The first thing that I see is the size of the sculpture. Not only is Ugolino larger than life, but the sculpture is placed on a pedestal, making the sculpture tower over its viewers. The second thing I see is Ugolino’s face. It’s twisted in anguish, and he’s not just biting his fingernails, he’s gnawing his flesh. I can see his teeth. And his finger between them. His eyes are sunk and drawn, and he furrows his brow, driving it down into the top of his nose as his gaze bores into some distant object.

Everything is tense. Ugolino hunches over; he draws in his knees and arms. His fingers rake at his face. And his toes. He has one foot over the other, near a chain fastened to the ground, and he clenches his toes in an angular pedal death-grip. His spine rolls up his back. The skin draws tightly over every bone, tendon, vein, and muscle. The only things keeping him from imploding, it seems, are his sons.

The two larger boys grasp and cling to their father. They force their arms and bodies into the few crevices that Ugolino leaves them. The eldest wraps his arms about his father’s legs, and I see where his fingers press into the calf. The boy’s mouth is open, his eyes wide, his brow raised. He looks up to his father, gaping. The second son burrows his head and arms into his father’s midsection, his back providing support for Ugolino’s elbow. His face hides within the crook of his arms except for a single, squeezed-shut eye.

The last two sons, far from tense, are limp. They look like they’ve fainted from exhaustion. The larger of the two sits on the eldest brother, and he would fall forward were it not for his arm extending out upon his father’s leg, his hand between the knees. His mouth, like his brother’s, hangs open, while his head careens back upon its neck, but his eyes are closed in fatigue.The smallest of the sons slumps beneath the second eldest, at his father’s feet. I see him lying almost completely horizontal, except that his head is propped up by his father’s ankle. His chin rests on own chest, and he seems to be sleeping. His face is the only part of the sculpture that appears peaceful . . . and yet, in some ways, it’s the most unsettling.

I didn’t have to know that Ugolino is a character from Dante’s Inferno who has been sentenced to starvation for this sculpture to make me feel queasy, or that his sons have offered their own flesh to sustain him for this scene to turn my stomach. I just had to look and see.

After looking and seeing for about twenty minutes, I hadn’t realized how much it had taken out of me until I went on to look at other works and felt that I had had my full for the day. But I’ve only looked at one thing! I thought, frustrated that I was tapped out far sooner than I had been during my past experiences with museums. But the fact of the matter is that I’ve never used these muscles before. On field trips I neither looked nor saw; I glanced. I check-marked. And so my legs would become tired before my brain. But now, it’s the other way around, and maybe next week I’ll be able to handle more than I did yesterday, and hopefully I’ll begin to actually “receive” the works. Lewis talks about crossing “the frontier into that new region which the pictorial art as such has added to the world,” and that’s where I hope to eventually go.