Last April, I was in a strange place. To be specific, I participated in a group show at Alogon Gallery in Chicago curated by Dayton Castleman, titled “The Strange Place.” Alogon Gallery asked Castleman to curate an exhibition after witnessing a discussion between him and James Elkins on the topic of Christianity and art. At the time, Castleman was finishing his M.F.A. at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and taking a class from Elkins, who was his advisor. One of the gallery owners of Alogon happened to be in the same class and witnessed the discussion, noting its value and wishing to carry it forward. James Elkins has recently become the go-to guy for discussions about religion within the art world because of his reputation as a prominent art historian and his 2004 book, On The Strange Place of Religion In Contemporary Art.

The exhibit’s title was an obviously direct reference to Elkins’ book. In the text, Elkins describes what he considers the problem of integrating religious belief with the process of making art within the contemporary art world. His examples come from his personal experience with students in the Art Institute. In each case he demonstrates how the student’s approach to religion within their work is unsuccessful. Within his own data set, his argument is rather easily proven. Most of the pieces he examines do fail in specific ways. But there has been considerable bristling from within the Christian community at his taking a representative sample from such a narrow group and judging the entire population by it, thereby ignoring recognized contemporary artists who address religion in their work.

Elkins also sheds light on is the seeming lack of understanding of or ability within the contemporary art world to dialogue about religion as an aspect of an artwork in gallery and museum settings. Another art historian, Dr. James Romaine, corroborates as a case in point that he (a relatively unknown art historian at the time) was asked to contribute an essay regarding the religious aspects of a Robert Gober installation for a major show of the artist at Matthew Marks Gallery in New York City in 2005. The show prominently featured a sculpture of a headless Christ on the cross, among other pieces. To Romaine, the irony was that no one had written specifically on the religious significance of such imagery in Gober’s work (this was not the first, nor most overt example); Gober is an artist about whom many articles, press releases, books and catalogs have been published, yet when a highly publicized exhibit of his work appeared, acknowledgment of its religious aspects were not found among mainstream critics or historians. Both Elkins and Romaine note a nearly complete avoidance of conversation regarding religion within the galleries, museums, and institutions of the contemporary art world.

For his part, Castleman decided to address the conversation regarding Christianity, religious belief, and the practice of making art by simply organizing the show in a unique way. He invited eight artists with whom he became acquainted through the Christian community rather than the art world to display recent works; he knew the artists first as Christians, and later as artists. The pieces submitted by the artists didn’t have a conceptual or aesthetic tie to them, or even a similar subject matter – although in two cases work was selected from an artist’s ouvre that directly related to religion. Albert Pedula’s “tanographs” look startlingly like the Shroud of Turin, as well as my own “Jesus Portraits” of people dressed in a “biblical wig and beard.” In both instances, the work was representative of the artist’s general practice.

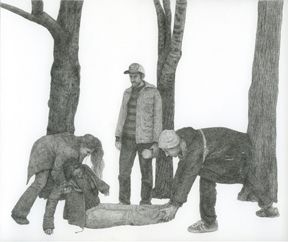

The largest contribution to the show was a series of drawings by Philadelphia-based artist Rob Matthiews from his Knoxville Girl series. The drawings trace an enigmatic and murderous excursion of a group of college-aged partyers, a tale based partly on a true story from the Tennessee town and partly on an old folk ballad. There is certainly an air of moral implication to the work, but no specific religious reference. Other artists displayed a wide range of work – from Rubens Ghenov’s drawings to paintings by Keith Crowley, Mark Dixon, Tim Gierschick, and Ben Volta to the free-standing sculptures of Gene Schmidt and Dayton Castleman himself.

I visited the opening of the show with Gene Schmidt, and it was interesting to observe that the premise was enough to allow such a disparate collection of work to be installed together without coming off as disjointed or haphazard. Indeed, while the knowledge of the religious standing of each of the artists was a significant awareness, the arrangement of the show was such that each artist had sufficient space to have his work be considered individually while not being disconnected from the whole. As his statement in the press release says, Castleman was admittedly not trying to set up a “…final word or solution to the issue (of religion and art)…” but “…as an occurrence that could serve as a discrete point of reference within an ongoing conversation.”

The result was exactly as Castleman had hoped. The opening appeared to generate a largely positive and lively response as well as a number of conversations about artists and how religion related to their work. The importance of this show successfully happening in a public and contemporary gallery space was certainly not missed; it was a refreshing spark of hope that religion, and specifically Christianity, could be discussed, critiqued, and even celebrated without a harshly reactionary/secular or blindly proselytizing/evangelical bias. A middle ground seemed to be established and participants from any side warmly stood thereon.

This is why I think “The Strange Place” is such an appropriate title. It took courage on Castleman’s part to organize a show that exposed both himself and a number of his friends to the scrutiny and criticism of a traditionally secular industry that tends to react against rather than promote religious work. It also took courage on the part of Alogon Gallery to be willing to host a potentially controversial and unpopular show. For me, the dialogue that surrounded the show was more significant than the fact that I had work hanging in it (although I feel tremendously honored and grateful to participate). If a civil, lively and productive dialogue can result within the context of the contemporary art world, it can (and should) happen anywhere. Indeed, it encouraged me to look for ways to find myself in a strange place again and again.

| Some Work from “The Strange Place” |

Timothy Gierschick |

|

|

Rob Matthews |

|

|

Albert Pedula |

|

|

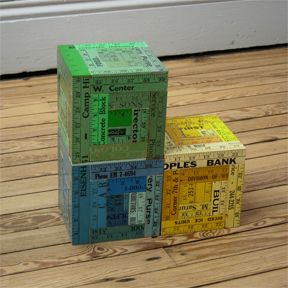

Gene Schmidt |

|

|

Wayne Adams |