Frederico Fellini’s 1963 film 8½ is brilliant for many reasons I won’t pretend to fully understand. But at the center of all its nuance is Fellini’s ego. In 8½, Fellini created a complete picture of his soul, his ambitions, his sexuality, his narcissistic attitude, and his interpretation and creative organization of the environment around him. He synthesizes all of the poignant elements of his life into a new narrative with as much emphasis on dreams as on reality, and with as much detail in the characters’ dialects as in their dialogue. The result is odd, indirect, and poetic, and as a unique glimpse of human nature, it’s as vivid and as challenging as a piece of art can be.

What’s interesting about 21st-century creative work is that, due to the revealing nature of the Internet, fans can become aware of an artist’s narrative prior to encountering the art itself. With the help of a couple quick wiki searches and a trip through some credible blogs, the public can become experts on an artist’s background and aesthetic inclinations. In many ways, this can hurt the artistic process: art no longer stands by itself because it must be accompanied by an online marketing campaign. Listeners might fail to meet art on its own terms because of the source through which they discovered it. Artists may find their art glossed over in the mass consumption of streamed music and film. The list goes on. In some cases, this runaway commodification can benefit the artist and his work; in these cases, there is a sense in which it allows for the telling of a three-dimensional, all-encompassing narrative à la 8½.

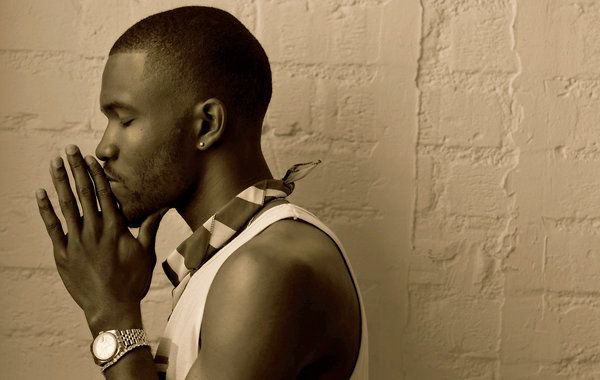

Frank Ocean’s debut album channel ORANGE may be permanently defined by the online letter he wrote to his fans two weeks before the album’s release. In the letter, Ocean chronicled his confused sexual history in profound poetic language. The takeaway for most mainstream media sources was that hip-hop and R&B were finally becoming civilized: a popularly accepted black artist came out of the closet, thus transforming the rift between black music and the gay community into an accessible platform for principally pluralistic conversation.

While this may be the case, what shined through more clearly was Ocean’s intimate understanding of the human condition, and the unique vision with which he sees it. Toward the beginning of his cryptic letter, he laments, “In the last year or three, I’ve screamed at my creator, screamed at clouds in the sky for some explanation. Mercy maybe. For peace of mind to rain like manna somehow.”

Frank Ocean is no stranger to turmoil. Through the course of channel ORANGE, he notes the financial troubles of his youth, the foul nature of his own self-indulgence, his sexual anxiety, masturbation, the harshness of urban life, and unrequited love. He weaves each of these tragedies into the sprawling narrative of his own experience, making use of a number of fascinating characters.

There’s his mother in “Not Just Money,” a junkie in “Crack Rock,” a romantic in “Pilot Jones,” filthy rich suburbanites in “Super Rich Kids,” and of course Ocean himself bookends the album with the opener and blogosphere favorite “Thinkin Bout You”, and then the heart-breaking “Bad Religion.” His place in his own narrative becomes clearer in the big picture of the album: he’s the only character whose problems are all internalized. In a world of drug struggles, crimes, low incomes, and rampant sexuality, Ocean stands out as the troubled artist who sees things simply and seriously as they are, and is able to explain them eloquently.

What’s more is that he creates this stunning mural in such a musically rich context. Comparisons to Stevie Wonder are unavoidable: his buttery voice and intricate musicality harkens back to Stevie’s daring pop-oriented aesthetic. He’s not the musical innovator that Stevie was, but his capacity for phenomenal melodies and his fresh take on R&B lyricism prove him to be comparably gifted.

As a lyricist, Ocean communicates through a topsy-turvy dialect of extended metaphor and cleverly juxtaposed imageries. In “Sweet Life,” he describes the relationship that his real life characters have with his music:

The best song wasn’t the single

But you couldn’t turn your radio down

Satellite needed a receiver

Can’t seem to turn the signal fully off

Transmit the waves

You’re catching that breeze ‘til you’re dead in the grave.

Later he continues, “But you’re keepin’ it surreal / Not sugar-free / My TV ain’t HD / That’s too real.” Perhaps the pseudo-realism of popular media, whether in television or in his own art, is too much to bear. He and presumably his listeners are overwhelmed by the realness, the sweetness, the intrigue.

Drake describes the state of hip-hop and R&B this way: “A time where it’s recreation / To pull all your skeletons out the closet / Like Halloween decorations.” But where Drake and others (see The Weekend or The Dream) use their music as an outlet for harsh confessions, Ocean goes deeper: he sings with poetic integrity, creates fitting, elaborate musical soundscapes, and invites his audience to engage in the reality that he has constructed. This isn’t The OC, this is 8½.

Without a boring moment, a twinge of artistic self-indulgence, or triteness, Ocean opens a window into the human condition, and peers in fearfully. It’s beautifully simple. In the summer of 2012 this unexpected masterpiece was a breath of fresh air compared to the drone of the radio (I’m looking at you, Pitbull). I, for one, can’t wait to see what’s next for Frank Ocean. Here’s hoping he gets that manna.