“There is something deep within us, in everybody, that gets buried and distorted and confused and corrupted by what happens to us. But it is there as a source of insight and healing and strength. I think it’s where art comes from.”

—Frederick Buechner, Of Fiction and Faith

My husband and I woke up late that day. We basked in our again-quiet home after the fun hustle and bustle of family and friends during the Advent and Christmas festivities of the past week. We sipped coffee; perused Facebook, Twitter, and whatnot; and I flipped through glorious new books that I had received as gifts. I pondered a mental to-do list of creative and domestic tasks that I wanted to improve upon there at the tail end of December and onward in 2012 — writing projects waited at the top half of that list.

At some point, Johnny and I looked at each other and he said, “Do you want to see a movie today?” We agreed on a Mission: Impossible — Ghost Protocol matinee. He ordered our tickets online. With a few hours to kill, we glanced at our new rollerblades, Christmas gifts from my mother-in-law. Mine were beautiful to behold: gray and silver with a hint of soft pink. My husband was a rollerblading pro; I was an excited novice. We both strapped on sturdy elbow pads, wrist guards, and knee pads. We stepped on to our back patio for my first lesson.

Johnny will tell you that I did very well. I became comfortable standing and walking on two lines of wheels as well as slowly rolling over the concrete. Even my first attempts to push off with each foot were typical for a beginner. I fell twice correctly, on my knee pads. I got right back up and kept trying to push off with more finesse. I felt tired from playing hostess during the past week, but I had fun, amazed at my progress. I daydreamed about skating on our favorite wooded trails in the park. We decided to end my lesson in order to make it to the movie on time. I guess my weary body leaned back slightly, my brain signaling the impulse to relax. I felt the slightest sense of accidental rotation under my feet and then time poured slowly like molasses during my descent. My left elbow and the concrete collided to stop my fall. A shockwave of nausea bolted down my entire body. Johnny repeated, “Are you OK?” several times before I managed to whimper, “No. No, I’m not OK at all.” He pulled off my skates and pads and I somehow got to my feet and into our bed.

We never did make it to the movie theater.

We called my dad, a coach who has seen numerous injuries, for advice. After icing my elbow for almost an hour, Johnny asked me to lift my arm. I complied, thankful for frozen water’s numbing properties, hopeful for a severe sprain.

“Jenni, please try to lift your arm.”

“I did, Sweets. See? . . . Didn’t I lift it?”

My husband’s kind face told me that no, I did not lift my arm. “Just your fingers,” he said.

In the car, I held my left arm next to my stomach in the only position that did not cause the sharpest, worst pain I had ever known. I sobbed and prayed in the waiting room of the emergency clinic. I heard my name. The professional, cheerful countenance of nurses melted off a woman’s face as she looked at my tear-stained eyes, then the self-protective clutch of my arm. I noticed her petite frame and crew cut as she held the door and said, “Come on back, honey.”

I have a strong adversity to the inhumane practice of torture, even unto our enemies. That day in the clinic reaffirmed my stance. An X-ray technician asked me to let go of my left arm, place it on a white table, and create acute, right, and obtuse angles. I looked at her in bewilderment. “I will not lie to you,” she said. “This is going to hurt. But I know you can do it.” I cried out for miraculous aid. Moving my arm literally centimeters at a time, we managed to capture three X- rays of my bones. Afterward, I held my arm as if consoling a suffering infant, and watched the male nurse practitioner’s face say, “You have a compression fracture. Your humerus bone pushed into your elbow joint. You need surgery as soon as possible.” I heard Johnny ask him more questions as my eyes glazed over. The eight-hour abdominal surgery I had two years ago to remove stage 4 endometriosis seemed like mere seconds ago. Another surgery? No. Please, Lord, no.

***

I’m not traumatized by the long, jagged scar on my arm anymore. The creepy criss-cross nylon stitches are gone. Now a slowly fading red streak marks my skin like a testimony. I don’t show many people the scar. But when I wash my arm with peppermint soap in the shower and feel one of the titanium plates — part of the new scaffolding of my elbow — I marvel. How far I’ve come. How far I’ve yet to go.

***

I was rolled to a surprisingly beautiful hospital room — modern decor and soothing paint colors. Vibrant pink azaleas awaited me, an anniversary gift from Johnny. It’s not exactly how we planned to celebrate nine years of marriage. He joked, “Honey, I also got you a new elbow for our anniversary!” My left arm felt like a foreign object due to the nerve block medication. Before surgery, I had serious trepidation about this procedure — I did not like the idea of my arm feeling paralyzed at all. But apparently I woke up in surgery recovery begging for the nerve block. I do not recall this plea.

Back home, Vicodin and a nerve block pump soothed the pain somewhat, but not my soul. I slumped in a chair which provided a view of windows inked with night obscuring the back patio. I looked away from that space of refuge which had turned against me. One of our cats jumped in my lap. I shrieked in pain. I stared at the bamboo floor, looking for shards of my life that broke and fell to the ground along with my body.

Johnny tucked me into bed — on my back, my bionic arm propped on a pillow. I looked past the ceiling fan trying to find God above the slow rotations of each blade. If I couldn’t sleep on my back, I slept sitting up on the couch, a fortress of pillows surrounding me, staring at the peaceful Christmas tree lights through a fog of drugs. Two comforts I had taken for granted — our pets’ affection and restful sleep — were taken from me. My left arm was taken from me. I wondered what other comforts would be swiped from me as well.

Unable to go to church for a month or two, our priest, and our friend who is a deacon, visited our home to minister Holy Communion as the fireplace softly crackled. Friends dropped by to deliver meals and share conversation and laughter. My brother took care of me when Johnny had drum gigs. Other friends sent thoughtful, encouraging cards and gifts in the mail. My parents stayed with us a few days to help with all manner of things — above and beyond duty, typical of their generosity. I felt overwhelmed with gratitude for these beloved people in my life. Not only was their help invaluable, but they didn’t care that the only clothes I could manage somewhat comfortably were oversized T-shirts and yoga pants.

The routines and rituals that framed my days ceased to be comfortable. The illusion of autonomy dissipated as pain walked alongside me, persistent. Unrelenting. And Johnny had to help me with everything. Even bathing. During the two weeks before surgery, we passed my broken joint back and forth with tactical precision to keep it still as he slipped on a large plastic sleeve to make the splint waterproof. One little slip and I shrieked in pain again. After surgery, I did not have the flexibility or strength to shower and so my husband continued to help me. I couldn’t explain to him how to blow-dry my hair, so he pulled it back in a ponytail instead. I often thought of one of our favorite annual liturgies at church — Maundy Thursday. The foot- washing ceremony is special to us, and humbling. We kneel to wash one another’s feet, drying them with simple white towels. Then we stand, our shoulders parallel to the altar, and give each other a holy, romantic kiss.

Soon it was time to start physical therapy which ushered in a new liturgy of pain, but I knew that these exercises were the only way back to normalcy. I acted like a tough coach’s daughter as best I could, but one particular exercise almost undid me. A therapist pushed my arm as flat as it could go, then pushed it toward my body as far as it could go. That inward push would prove to be the most difficult motion to accomplish. After a while, the therapist decided to push my arm inward even further. I breathed as if I was in maternity labor, tears blurred my vision, and when he was finished, he said, “Good job! And by the look of your bloodshot eyes, I can tell we made some real progress today.” Johnny had to act as my therapist at home. It wasn’t easy for him to inflict such pain upon me, but we slowly started to see progress and flexibility. And I do mean slowly. Due to unnatural sleeping positions and reintroducing my body to movement through physical therapy, I developed muscular pain in my back — another problem to tend to. We both needed a reward for such hard work, so after sessions at the clinic, we dropped by a Turkish restaurant for hummus, tabouli, beef and chicken shawarma, pita bread, coffee, and baklava.

***

“Behold, I am making all things new,” says Jesus. The order of my life was revised by the Author of my faith. He also said, “Write this down, for these words are trustworthy and true” — an eternal decree to St. John, but also to me, a writer. Elbows and wrists are fearfully and wonderfully made, created to work in synchronicity. But they are also created to suffer in synchronicity. I could barely lift these bone-hinges to type a sentence. I took to henpecking with my right hand fingers. How will I ever write again? . . . Who cares. My writing voice was snuffed out by trauma, pain, fatigue. Disillusionment of the Lord to whom I pleaded.

I should have journaled with my favorite pen. I did read. Jeffrey Overstreet’s fourth novel in the Auralia Thread series, The Ale Boy’s Feast, whisked me back to The Expanse. I yearned for a redemptive conclusion to the imaginative and complex plot twists. I rooted for the people of House Abascar trying to find the mythic city they searched for in faith, and Auralia’s colors which gave them hope in the darkness. I also read Lauren Winner’s Still: Notes on a Mid-Faith Crisis, another timely read. I felt stuck in a mid-faith crisis of my own — not only trying to be patient with my elbow, but just trying to be patient, to trust God with what (psychologically) felt eerily similar to what Johnny and I went through during my previous, epic illness and equally epic surgery. I could not figure out why we had to switch domestic roles and endure physical suffering again. I didn’t turn my back on God, but my prayers were tinged with anger, mostly questions and laments.

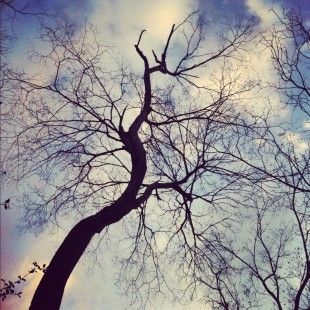

I managed to snap Instagrams, delighted when I could raise my left arm a bit higher to frame the photographs. One of my favorite subjects were trees on our favorite walking trails. The bare winter limbs seemed as fragile as my bones, yet breathtaking as they reached up to the winter blue sky. I knew by spring they would be lush with green. I looked upward and hoped that my elbow would flourish along with the foliage.

But I still did not write. I let Instagrams speak for me, with meager, malnourished captions. The visuals often surprised me, though — the beauty of God’s creation and peace within our home glowed with a retro, holy patina. I rested on the editorial side of my brain, satisfied to share the words of others on the Art House America Blog, hiding my words behind my back.

Obviously, I used my laptop to publish issues of the Art House Blog. I was able to type with more ease as time went on. Self-denial wore off pretty quickly. I possessed a strange dichotomy: I felt empty, but my being brimmed with words. I desperately needed to process my thoughts with a pen or the percussive rhythm of typing, but I was scared. It wasn’t mere writer’s block. I had pretended that writing didn’t matter for so long that I was beginning to believe a lie.

I forced myself to sit at my desk and write anything — short book reviews on Goodreads, journal entries, and so on. What trickled forth was this very piece. It has been a rough reentry. The process has been physically painful at times and mentally taxing. Dreamy inspiration has not spurred me on — I’ve eked out sentences literally one word at a time. I’ve recorded deadline after deadline in iCal that I did not meet.

I’ve often confessed my lack of writing these past eight months. I’ve repented of falling behind in some of my other work, too, and for the many unanswered e-mails waiting in my inbox. I beg for God’s mercy through the colleagues I’ve disappointed. During one of these quiet moments of contrition, I wept as I recalled a well-known verse from Psalm 51: “Let me hear joy and gladness; let the bones that You have broken rejoice.”

To be honest, I never really had a great writing discipline. One mysterious blessing to come from breaking my elbow and all that ensued is a fairly recent but fervent desire to write again, every day. As Anne Lamott is known to tweet, “Butt in chair, bird by bird.“ Word by word. I thought this article would never get written. It is probably not my masterpiece. But it is a piece of writing. And when I click command-S to save these words for the last time, I will have overcome the wordless months behind me. My writing voice once was lost, but now it is found. Come what may, I will never silence it again.

All photos are courtesy of Jenni Simmons, whom you can find and follow on Instagram.